Interview with Lee Perry

by Geoff Stanfield – Mar/Apr 2020

When you first started making dub records, what made you want to use echoes and reverbs? The music’s so transportive, and it’s different than roots reggae, which tends to be sort of dry.

Echoes make thing sound different. You can repeat yourself in echo. If you want to say one word, and you want it three times, you put it in three-times repeats. I program; I command my word to be on top. And I command myself to be The Upsetter. And I command my song to be The Upsetter. And I command myself to be on top.

It is transportive. It takes you to another place.

In space. In orbit in the galaxy. I program myself in the galaxy.

Echoes.

Echo and echo ameco. I am peco. Gecko. Why do you want to send your tupecko?

How old are you now?

Eight million, trillion, centzillion years.

Why do you keep doing this?

Because I’m the beginning and the end.

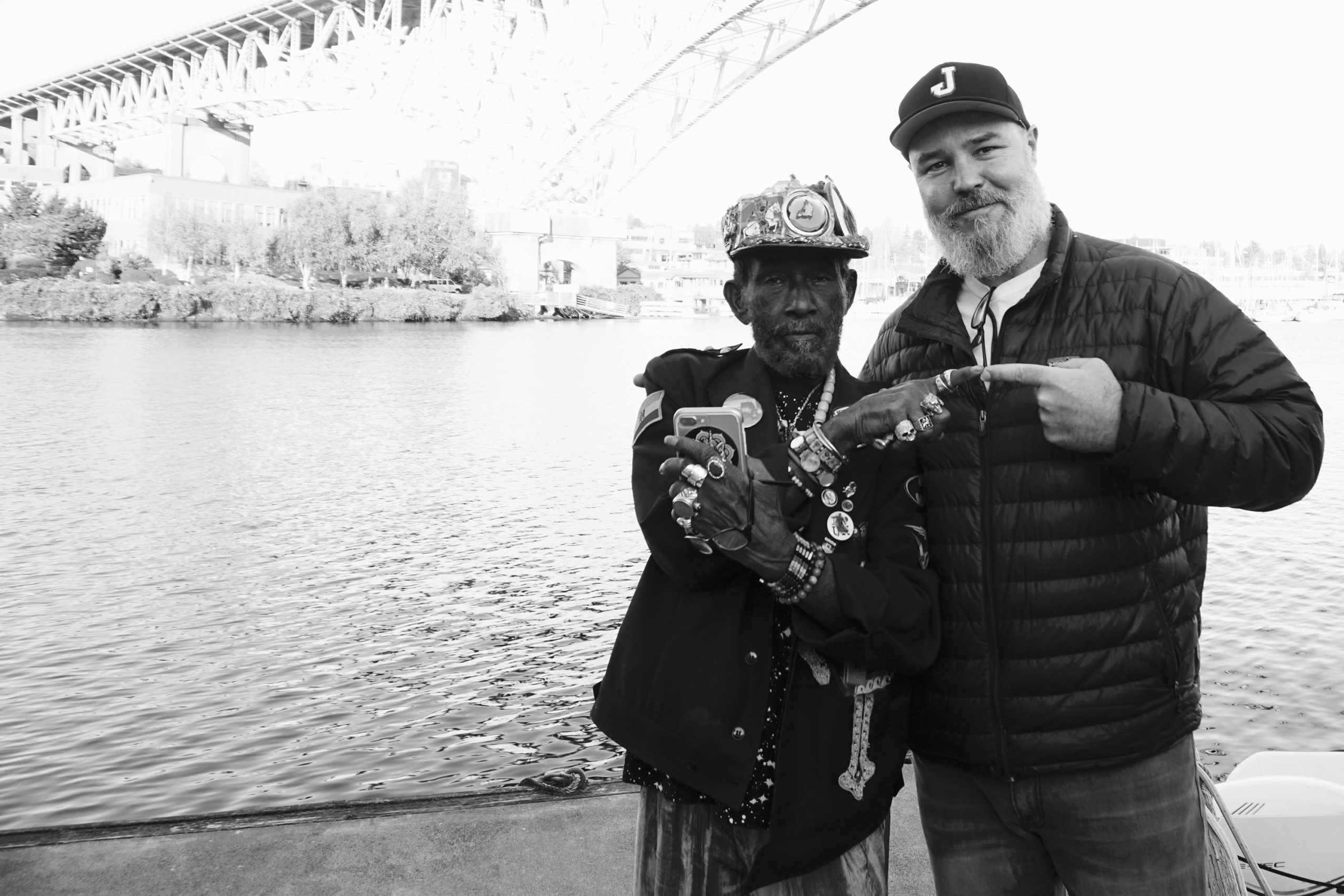

How did you come to work with Emch?

How he came to work with me, I don’t know. It just happened.

But collaborations have been important for you.

We were drinking rum, someone was drinking wine, someone was smoking cigarettes. Someone was smoking ganja. Illness is a curse. I wish nothing to be ill. No Illuminati for I; I kill Illuminati, and kill the Luminati. I have no use for them. Really jumpy, like the lady butterfly.

Man, I could talk to you all night. Pure magic.

Yes, pure magic. I fill the earth with magic.

Did you really burn down the Black Ark? I thought it was your studio.

But to what evil it was. A vampire; a bloodsucker. It filled me with fucking dread.

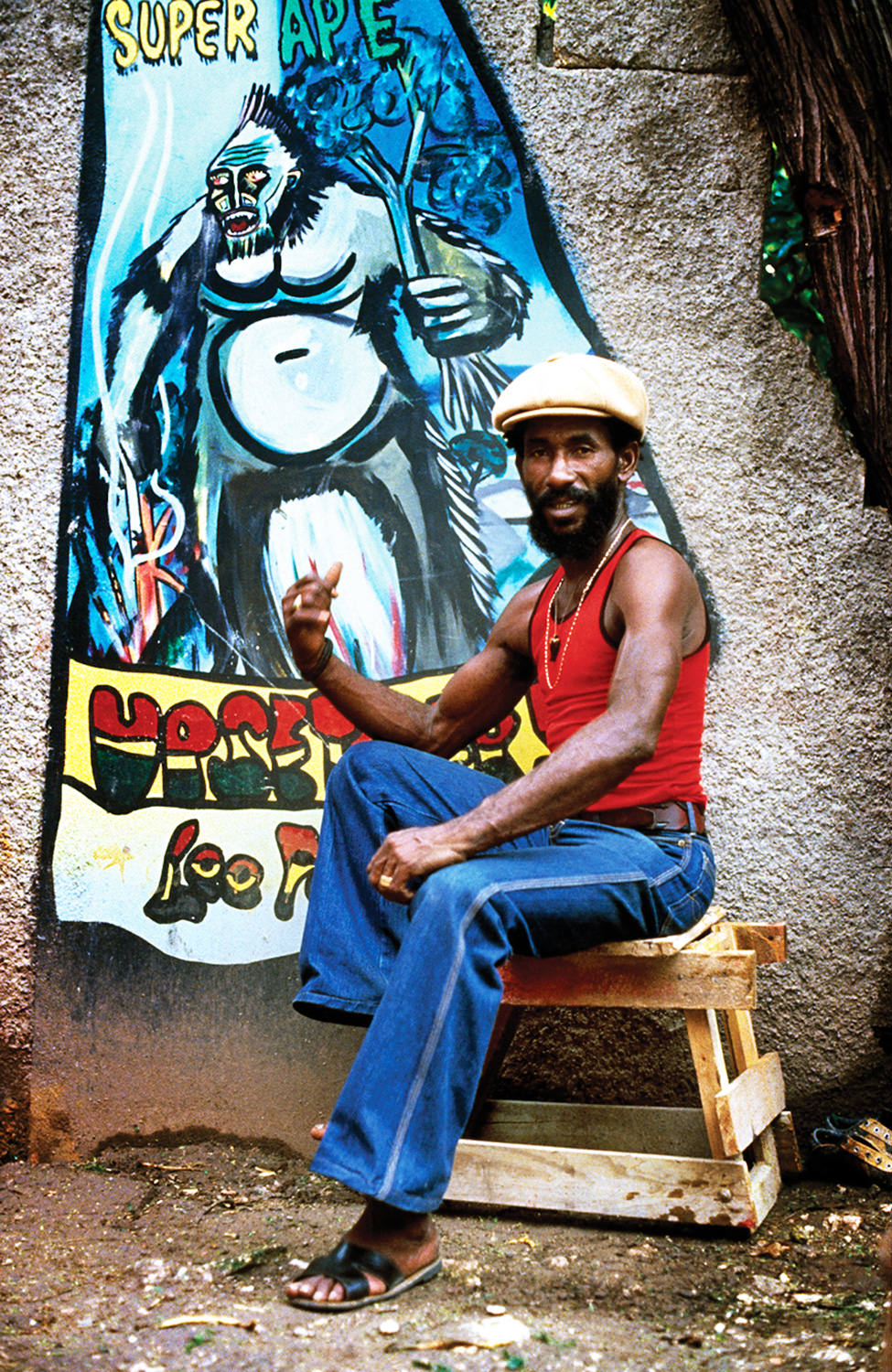

You made the Super Ape album in 1976, and now you have Super Ape Returns to Conquer.

Super Ape is the world. Super Ape is the universe. Super Ape is God.

Are you the Super Ape?

I’m the creator. If I tell you who I am, I would expose the secret. I am a secret. Right? I am a secret from the Black Sea. The Black Sea, you find me in the Black Sea. You find me in the Red Sea. As if I’m in the Dead Sea. Who am I?

I’ve heard you say you’re a fish.

You’re right, I am. Good.

What’s the purpose of the mirrors on your shoes?

You can see yourself in a mirror. That’s the first mirror. I made a second mirror. You can look in the water and see your shadow. I had a vision of red, black, or white.

I love your music. You change lives.

Maybe that’s why you love me.

From your first record to the last, it’s one big circle.

The music is perfect. I’m sure the music is perfect. I am a mystic. I am a fish. I am a chicken.

Can I take a picture of your hands?

If you wish. [See this issue’s front cover.]

They do the work.

When you’re ready, say you’re ready. Are you ready? The music don’t make mistake, the music don’t eat beef steak, the music don’t eat fish steak, the music don’t make mistake, the music don’t cry, and the music don’t lie, because the music is immortal, and the music refuse to die, and the music refuse to cry, and the music refuse to lie, because the music is not a mortal being. Music refuse to be a human being. Music will never be a human being because the music is the great supreme.

I left feeling blessed to have interacted with Lee, but was also a bit mystified by what had just happened. It became obvious quite quickly that my list of thoughtful questions were no longer relevant. So much of what Lee “Scratch” Perry does is improvise. He reads the room, feels the spirit, and accepts divine intervention. I spent years studying and playing jazz and improvising; I just didn’t realize that these skills would be expected of me in an interview one day. This was like stepping on stage with John Coltrane, or into the ring with Muhammad Ali. All I could think was, “Pay attention and listen.” After a day to reflect on how I failed to get much of an interview out of Lee, I had a brief call with Emch to discuss a better path forward. He suggested we talk about the elements. After brief hellos and a tour of my studio space, which he was very interested in, I put Lee in a big gold chair for our interview. After my first question he asked for tape head cleaner (alcohol) and proceeded to light his shoes on fire.

How did you make this Lee “Scratch” Perry record, Super Ape Returns to Conquer? Was it from existing tracks you remixed or reimagined, or did you try to recreate the original record?

Emch: Scratch gave us the blueprint, but we were reproducing his production in a way that isn’t a copy. He always talks about not wanting to be a copy. We did something new with it that represents his energy and how he’s feeling now. I feel like what we tried to do with…. Returns to Conquer was create something based on his own history, and then pull in elements of the things that have evolved from what he created, like making the bass subbier and wobbly. What we hear in dubstep, as well as other music that has grown out of what he’s done. I feel like if he made the record 40 years ago, it’s still 40 years ahead of its time anyways. Now we’re making it to hopefully be 40 years ahead of today.

At Black Ark you only had eight channels to work with on the board.

We had four, at first.

Lee, when you originally mixed and produced Super Ape, was it on four tracks or eight tracks?

Well, to the surprise of the world, it was one thing I had in mind. You call it the world, and the globe, and the universe, and the creator, but we have one name for the world. It’s Super Ape. Only one world, Super Ape. One globe, Super Ape. One universe, Super Ape. One magic, Super Ape. Super Ape is shit, as most of the people complain about when they interview with me. Shit is Super Ape, and not many people like shit. Many people eat shit. I wanted to accept that this night people eat shit. It’s playback, replay, feedback. Record it. You play it back and listen it. You video it, and replay it, and play it back. That’s hearing, seeing, smelling, and tasting the invisible. Shit. Nobody love to smell shit. Shit is the power and the glory. Shit. Shit is the power and the glory. Shit. You can sound like Bob Marley. [plugs nose and mimics Bob Marley singing] Vanity is not a blessing, but the power of temptation, yes? You keep it, if you have to. But my shit is precious shit. In my interview with most people, we talk about shit.

Talk about rock stone.

It turns me on.

It does.

For real.

What about it?

It gives me the energy of the earth stone; it’s rock stone. The earth love people, and people like rock stone.

When you were first starting to do dub remixes of records, that was not a traditional path. That was not what people were doing. What made you want to use echoes and reverbs, as well as deconstruct the music down to its core?

My shadow. My shadow. It inspires me to do everything. My shadow looks at me and says, “What color do I have?” If it sees black, I’ve got black. And God is black. And don’t be flying in the room. Don’t be flying on the moon. God. Don’t fly on the moon too long.

Emch: Shoot them down. Gotta shoot them down.

Shoot them down.

Emch: I heard Lee say that a lot. People getting caught up, especially singers, in the vanity of things; the whole rock star side of things.

The name I have for them is reggae duppies.

Emch: That’s ghosts; like evil spirits. But dub never was intended to be pop music. It was like a spiritual music.

Soul music, pop music, rock music. Dub is. God made me supreme. Supreme. Superman. Supreme superman over duppies.

Yeah. I’ve heard you talk about killing vampires.

A vampire is a duppy…

Emch: He wrote the song “Duppy Conqueror” for Bob Marley because he told Bob he had a duppy haunting him and it was the reason he couldn’t rise up and be successful. He wrote that song and Bob sang it as a spiritual cleansing to chase them away.

Duppies. Duppies. They want to get rich. They want a ring to get rich. I’ll give them a debt met to life. I said no. I said maybe. May-be. But no! No! No! You will die. Nah man, got killed and die. And they said, “No more! No! More! Kill them dead.” They said, “Neh. Don’t try you die!” And ooh; God belched.

That’s the end of the story?

That’s it. When God belched, he pooped too.

Emch, after having hung out with Lee, if you were going to explain dub to somebody who’d never listened to it, what are the essential elements of dub; other than Lee, of course?

Emch: Yeah, “Scratch” is the essential element. The X-factor.

If you need another me, you can ask Harbor Shark. The Harbor Shark lives around here. Maybe you could be the Harbor Shark.

So, Lee, why do you trust this guy with carrying on part of the tradition you created?

You hide all the money in the bank. Let me give you some money and give you a tip; but you’re going to have to earn the place, the Harbor Shark.

Emch: You want to cut a track called “Harbor Shark” right now? Could be a big hit.

Next time you come back I’ll be ready and we can do that. I’d love to.

Harbor Shark Records Present: Lee “Scratch” Perry, the King Fish, on the Harbor Shark label.

You’ve talked about being a fish, and about Neptune.

I’m a fish, originally. But I didn’t want to go in, so I applied Harbor Shark.

Emch: King Neptune is his father.

How do you work that in, your life in the water? How does that sound in your music?

Life in the water give me seven times the power. It’s a hidden light that tells me what I have to say. I feel a bird, right? And a cat’s coming to kill my special bird. My bird was a white bird and the cat was black and it got jealous. It killed my white bird. What do we do? We kill the cat! The cat killed my bird, and I killed the cat too. I got lost. I love cat and cat loved me; but killed my bird. He’s jealous. The cat is black magic. Want to eat all the birds. Want all the magic.

What you give is what you get, I suppose.

Maybe the cat was Bob Marley. He was a male witch. He killed my bird and I said, “You won’t get away. Sooner or later, I’ll catch up with you.” I catch up on black magic and I deal with black magic. I catch up with the black cat, black magic, and I decide I get even with the black cat. That’s just fun. Black Magic. Jay-Z teacher.

Jay-Z?

Jay-Z and Beyonce teacher. Aleister Crowley. Ill, very ill inside. So they want to be Illuminati. Ill doom and naughty. Illumi good. Illumi-gorgeous. Illumi-copycats. Illumi-rat and Illumi-ratbat. That’s a vampire. An Illumiratbat.

Emch, how do you take Lee’s guidance and integrate it?

Emch: I think it’s his full philosophy. We don’t really talk about music. A lot of times I do interviews and we don’t talk about music. This is how “Scratch” sees the world, and I think you’ve got to get on that wavelength. It’s osmosis. You just understand that worldview, and then you create accordingly. That’s what “Scratch” does. He listened to the sounds of nature and the sounds of God. That’s why his music has spirituality in it. In making music with him, to do it well, I think it’s not that we’re copying what he did; rather we’re aligning it with his vision of trying to create music that represents God, spirituality, and nature. In doing that, we’re aligned with him and can get along with him. Otherwise he’d be done with us. He’d suffer if we’re not paying attention.

That’s a very good point.

If you have a pen, a black pen, I’ll write my name. Your bodyguard is your music. If you’re in trouble, you’ll remember something. Stress is a joke. Stress also is a duppy. Stress. Stress is a duppy. You can’t survive without something to support it. Stress duppy.

You’ve had a long career. You’re still here. You’re still influencing a new generation of musicians and the music will live on.

You are very protected. You are on the water. If you want to be a Harbor Shark, you can be the Harbor Shark.

This place feels good because of the water. That’s why we surf.

You can spread it next. We do not fear the Harbor Shark. The Harbor Shark gives me protection. If you have a pen, I’ll write that.

Emch: He put on an art show with me a couple of years ago in Brooklyn. He’s done a couple of paintings. It’s very interesting to me to see his creative process; doing something other than music. It’s the same. He’s creative all the time, just nonstop. Other peoples’ minds are on other stuff. He loves that superglue. Apparently [Jean-Michel] Basquiat saw pictures of the Black Ark, and that was a big inspiration for him and his art back in the ’70s. His art had a lot of writing, as well as drawing, in it. He said he’d seen “Scratch’s” studio and all the words incorporated into it.

I’m very old, you know that? We have super children out of the sea, out of the water. Water is the life-giver, so anything water gives only fire can destroy. With water, there’s a combination.

How long have you been away from Jamaica?

Well, it doesn’t matter, because there is something inside the Jamaican people. You can’t be a hypocrite and tell the people you love them. That’s true. You stay away from them for a while. They want to be used. Not them alone. Africans see it too, and most white people see it too. People want to be used too much. That’s why I’m staying away from Jamaica.

Emch: A lot of people are jealous of his success. That whole thing with the Black Ark, there were so many people hanging around saying, “Make me the next Bob Marley!” They’re trying to take away energy; energy vampires wanting him to do things for them.

Lee, you are very giving. I watched you with your fans last night. You took the time to talk with people, take pictures, and sign things.

Emch: I think that’s the thing he’s saying. You can give to people who are going to give back to you, but if you give to people who aren’t going to give back and just take, they’re going to take advantage of that, and they’ll drain your energy and blood.

It’s fun. That’s why I believe in God; he was a fish and then he made us to look like man. What else can I say?

Emch: What does that mean for me? I was a wolf, and I still look like a wolf? Didn’t complete the change. I got stuck here.

What happened, Emch? You played the Super Ape so much your turned into the Super Ape? Talking fish, singing fish, walking fish, computer fish. It is crazy. It will be out of this world.

Super Ape Returns to Conquer is not the first record you’ve done together. How did the collaboration with Lee come about?

Emch: Just over time. I’m a student of Lee, like many people. Studying him and trying to support his vision. I first did some dubstep remixes for him ten years ago with a band he was working with. They liked it; it was something different. I know Lee gets bored very easily, so I pushed him to do something different with the live versions as well as the remixes. What happened eventually turned into what we have now. Lee doesn’t like to go back and do old stuff a lot. He doesn’t want to talk about the past.

If there’s a market for it, no problem.

Emch: Even when Lee sings the lyrics to his songs, he said to me, “Never do it the same way twice. It wouldn’t be honest. It’d be copying the way you felt in the past.” It’s always got to be some level of improvisation or something new. I think trying to make the music for the new album was a process of playing it [the original Super Ape] live so many times that you make something new out of it. So much music used to be that way, especially jazz. The history of music was playing music based on other music. Lee loves a lot of the ’70s Motown. A lot of reggae songs would start out with taking elements and creating something new. I feel like they were combining elements of that American R&B music with more African elements – like jazz and European instruments – and they created their own thing from the foundation of this music that was a part of their history.

What does water represent in your music?

That’s water. [points to the flames on his shoes] Spirit.

What does that represent in the music to you?

Without water, you are no life. Water create life. Without a fire, you are cold. You have water and iron, water and fire. Iron, that would be in your blood. I am banana man; I love banana. I believe in banana. The banana is in the music. The banana come by ganja. Ganja is the king. Fire is the king. I clean my throat so that I may speak. Do you have any wine?

You’ve talked about the heartbeat of dub music being the drums and the bass.

Yeah. The heartbeat is the drum and the bass is the brain. The bass is the brain. The bass come up with “poom poom.” Poom poom. Without poom poom, you can’t have any children because the bass is saying “poom poom.” The most poo poo. You know poo poo? Well, for you to poo poo, you need a hole to poo poo. And for you to go into a poo poo, you need a ti ti. So you play a cymbal. Ti ti ti ti ti ti, and then poom poom. Ti ti ti ti, bash. Poom poom. Ti ti ti ti pash poom poom poom poom poom. [repeats several times] That poom poom make babies. The poom poom is perfect and good for a generation to create.

How about echoes?

Bacteria. Not good. The music is nature. The music, is nature, nature. It’s all about sex. What kind of sex you deal with? You have holy sex, you have righteous sex, you have ungodly sex, you have good fuck, bad fuck, good luck, bad luck. Whatever kind of fuck you choose. The people who interview me and complain to me, people who have no sense. People who see the truth and complain about the truth; I am no use to them. If you’re not in the root, you won’t find out the roots. You have to be a root to find the roots. Dancing turns on anybody; to make people feel good. The music is magic.

Do you and Emch have plans to do more in the future?

The future! The future is a Super Ape. The future. The future is Super Ape. You are the first person to give you advice. The thing about Super Ape; Super Ape comes from another earth. Magic. Around the world magic. Men couldn’t stand up to the Super Ape, so it took invisible forces to hold it up there. Even some Americans went to the moon. They didn’t end up going to the moon because we have a doom, a holy doom. Holy doom. Everybody fights against the holy doom that turns them into maggots. Turn into maggot fly to torment them and turn into maggots to eat them. This is the holy doom. And the children doom. Then all the hypocrites to the doom, to eat their flesh and eat their bones and turn them into the dust of ashes. [singing] You follow I? Going to the sky, follow I; and don’t you lie, follow I. Go into the sky to fly like a butterfly.

It is not easy to interview Lee “Scratch” Perry. Whether it is a defense mechanism for fending off what he deems useless enquiries, or just a protection of self, it is a perfect representation of what his music represents. Playful one moment, spiritual the next, spacey to the left, murky and barely intelligible to the right. But through the haze, the words are lessons, as well as an insight as to how he looks at history, mythology, spirituality, and life.

https://aquariumdrunkard.com/2019/06/28/lee-scratch-perry-the-aquarium-drunkard-interview/

Interview by S. McDonnell

When I call up the reggae legend, Lee “Scratch” Perry, The Upsetter, to talk about his new album Rainford I reach him on a grainy WhatsApp audio connection. He’s in Jamaica and he’s in bed, “looking at the lights. looking at the day, and looking at the night.”

Perry’s in his eighties and when he gets going he speaks in limericks, but he doesn’t come across as wacky, just joyful. The first thing I notice about Perry is the giggle that roils through the conversation and punctuates his sentences. It’s disarming, a Buddha-like by-product of a lifetime of producing joy by way of deep and heavy rhythms, and meant for killing egos. “In my life, men come here to serve God but some come to profess their ego. You let them do what they want to do or they will try to kill you, if you try to stop them. Because their ego is their God!” He’s deeply serious about the mission of joy: “There can be nothing better than to make people feel happy. When people are happy, I’m happy. I will continue to make the people who believe in me and love me happier as long as I’m living. Under the sun under the sky. I want to make the people who believe in me happier, happier. So they can jump up and touch the sky, and the sky starts to rain!”

Joy permeates Lee Perry’s bright new album Rainford (after the name on his birth certificate) recorded and produced by Adrian Sherwood, himself a dazzling producer, (African Head Charge, Dub Syndicate, Mark Stewart + Maffia, Singers & Players), and released on Sherwood’s On-U Sound imprint. It’s very much an apex of Perry’s brilliant decades-long run.

Similar to the genre-defining career of Miles Davis, to follow The Upsetter’s rise is to follow the history of reggae music. “Lee was going from all this wacky, fast, gimmicky stuff in the ’60s,” says Sherwood. “Like ‘People Funny Boy,’ ‘Return of the Django,’ ‘Dr. Dick,’ both instrumental and vocal, and then when the black awareness and Garvey-ism and Rasta came in, he was at the vanguard of that as well.” Dub is the process of stripping a reggae song to its elemental rhythm, chopping up the vocals, enhancing the bass, and lacing the track with heavy echo and reverb. It turns roots reggae’s sunshine into something more repetitive, minimal, and psychedelic. “Lee was on the evolution of dub music,” says Sherwood, “the evolution of ‘version,’ because it used to be a boring instrumental on the B-side, and it evolved into exciting soundsystem versions for the DJ to go over. Lee was at the forefront of the most interesting things with that as well.” As a producer, Lee Perry laid the foundation for Bob Marley’s superstardom (“Small Axe,” “Duppy Conqueror,” “Kaya,” “Concrete Jungle,”). Lee says of Bob Marley: “He helped me transfer my message across to the world, and that’s OK!” But he expresses concern about a YouTube video that he saw that insists Bob Marley was “part of the bafflement” or in cahoots with bad spirits. “I don’t know if they were joking that he was part of bafflement, and dem tings. I didn’t know that. I don’t have to believe that, either. What was done was well done, and could not be better.” Somehow all of this — the joy, the gimmicks, Bob Marley, the mastery, the bass — is contained within the nine tracks of Rainford. “Lee’s made so many brilliant records,” says Sherwood, “all the gimmicky ones, all the rude ones, all the conscious ones, the dub ones. He’s incredible. I know that he can switch from being this child-like brilliant character to somebody who is very serious. He’s perceived to be a bit crazy and a bit jovial, but he’s a fascinating, fascinating man.” Rainford is heavy with ambition, a deliberate play at defining an artist’s legacy, and a Grammy contender. “I wanted at this stage,” says Sherwood, “to get an album out of him not dissimilar to the one Rick Rubin did with Johnny Cash. A later-in-your-career album that is actually a really strong piece of work and has a level of intimacy about it.” The intimacy comes from Sherwood’s history and care with Lee Perry, and is conveyed by sly musical references of Upsetter songs past. “Reference points,” says Sherwood, “fractured parts of Lee Perry productions,” appear throughout Rainford, “brought through the mangler. Bits of his old records cut into it.” The past building the present. The opening track “Cricket on the Moon” makes me wonder why there are so many animals in Lee Perry songs? “They were here before us,” Perry explains. “All we can do is love dem, care dem, share dem and don’t eat dem. Eat vegetables! I’m a Pisces, too – I’m a fish. I really like ocean. People eat fish, but I’m not complaining yet!” I am curious if Lee Perry ever had dreadlocks, so I ask him. “Never. I have no reason to do that. I am the child of a king and my king is a dread head. My king is dread, not dead. My king’s name is King Neptune. King of the moon, king of the stars, king of the sun, king of the rain, king of airplanes and king of trains!” Sherwood says there’s an arc to Rainford, it starts, “mischievous and silly, then [when it gets to] ‘African Starship’ it’s quite psychedelic. And then it gets very personal and very intimate.

The personal he’s referring to is “The Autobiography of The Upsetter,” the album’s core and its emotional culmination, a 7+ minute tour of Perry’s past, from birth to the present. It’s a starkly personal, serious–and rare–moment from the typically jovial Mr. Lee. Referring to a line in the song, (“My Father was a Freemason, my Mother was an Eto Queen, they share a dream…”), he wants to set the record straight, “My father was not a Freemason. That was a joke in there. It was a joke. My father was a free slave, who worked on the road.” “I pushed and pushed to get that autobiography out of him,” says Sherwood. “I had to coax it out of him. A lot of work went into that one tune.” It’s a beautiful and revealing song, one in a lifetime of beautiful genre-defining bass-heavy, bone-shaking songs. I ask Lee if he remembers all of his songs, hundreds and hundreds of them. He says he has an image of them. “Yeah, I’m got image. I don’t remember them all. But I am the image of God. When you are the image of God, you are there to remember the songs, every chord you play. You are watching the songs with your mind and body. I don’t have to remember all the songs. As long as they help you and are good for you, then they give praises to God and memory.”

https://www.uncarved.org/dub/scratch.html

Interview By Danny Kelly

New Musical Express, 17 November 1984. Pages 6, 7 and 58.

WHEN THE sprawling, jagged, beautiful, wicked history of popular music is definitively assembled, the name of Lee Perry will be writ large. If his sole achievement had been to engineer Doctor Alimantado’s ‘Best Dressed Chicken In Town’, a tune that fired the pimply imagination of John Lydon, he would have been entitled to a line at least. Or if he had only been the coproducer of The Clash’s fiercesome ‘complete Control’ he’d have deserved a small paragraph.

But Perry was also the man behind some of the greatest records ever made, reggae or otherwise. And the politics that drew the latent genius of Robert Nesta Marley to the surface. And the brains, ears and hands that helped create dub, an innovation that altered the sound, the very possibilities, of black music as surely as Leiber and Stoller’s inspired orchestral drenching of The Drifters’ ‘There Goes My Baby’ or the white-coated circuit-board wiz who gave soldered life to a micro monster and called it DMX.

In truth, the felling of all the forests of Scandinavia couldn’t produce enough pages to do justice to the wondrous art of Lee Perry. And yet, on one hazy Jamaican morning in 1980, this amazing man made an effort to write himself out of that history. He destroyed his fabled Black Art studio, his tiny haven of creativity that had become a torture chamber to him.

Perry’s legendary eccentricity appeared to have spilled across the invisible line into full scale insanity.

Since then all we have heard are rumours, spread, he claims, by his enemies, of continued madness, some third-hand quotes (some pitiably said, others laced with acidic anger) after the death of Marley, and a series of reworked rhythms put out on compilations by the miniscule Seven Leaves Records in North West London, welcome but nonetheless faded echoes of former glories, dusty crumbs from a table once groaning with bounty.

But now the Lee Perry legend may be on the verge of resurrection. An all-new record (‘History, Mystery, Prophesy’) has appeared in America and the genius is holed up in London, planning, scheming, plotting and ranting, preparing to tour and, joy of joys, to produce more new music…

Having tracked him down amidst the suburban bustle of Kensal Green, initial contact with Perry is disturbing. He is wearing a straw hat, a sequinned shirt and a woman’s cardigan. His small, wiry, 48-year-old body is incredibly fit, used to Kung Fu kicks way above head height. A video camera records my movements until the batteries run out. And throughout the interview, Perry thumbs the pages of a large book (about Marcus Garvey actually) and writes a selection of the words and phrases that I speak to him in large biro capitals across the dense text. I’d like to see Terry Wogan handle this.

But all these things are mere eccentricities, really. In conversation he is lucid, articulate and abrim with opinion. A torrent of language (punctuated with catch phrases, buzz words, references to the elements and martial arts gestures) issues from him, some of it pertinent and clear, some babble in unearthly tongues. He is currently obsessed with Island Records, or rather their head Chris Blackwell, who he feels has done him wrong.

I’m no psychiatrist but I don’t think Lee Perry’s mad, at least not now. In any event, he is willing to hold forth his views on his past, his present and his future, to set the record straight.

HISTORY

“MY FATHER worked on the road , my mother in the fields. We were very poor. I went to school, first in Kendal, then in Green Island, ‘til fourth grade, around 15. I learned nothing at all. Everything I have learned has come from nature.

“When I left school there was nothing to do except field work. Hard, hard labour. I didn’t fancy that. So I started playing dominoes. Through dominoes I practised my mind and learned to read the minds of others. This has proved eternally useful to me.

“After that I was getting to be a big lad sol decided to get a proper job. I became a builder, a driver of bulldozers. I liked the power! That BRRRRRRR from nine ‘til six. BRRRRRRR from the engine up the gearstick and into your arm, It builds up lots of power. The tractor driving filled Lee Perry with superpower!”

Fuelled with “superpower” drawn from large internal combustion engines and what he describes as “miracle gifts, blessing from God”, young Lee made his way to Kingston, a city of sharks and wolves. He infiltrated the peripheries of Clement ‘Coxsone’ Dodd’s sound system and record label, first as a glorified teaboy, late as a fully fledged disc spinner.

A victim of the violence that accompanied the sounds of Dodd’s renowned business sense, Perry’s lifelong hatred of his employers started in those heaving dancehalls and dingy studio sessions.

“Coxsone never wanted to give a country boy a chance. No way. He took my songs and gave them to people like Delroy Wilson. I got no credit, certainly no money. I was being screwed.”

In these mid-’60s days, Perry worked in the Federal studios before it went bust and the West Indies studio before it became Dynamic Sound. In the latter he organised a work now, pay later, session for himself and cut the record that freed him of Dodd’s yoke.

‘People Funny Boy’ (a vitriolic attack on his former guvnor) was “cut on the Monday, mastered on the Tuesday, out on the Wednesday and a hit by Friday”. ‘People’ opened ears to Perry’s talent as an idiosyncratic vocalist and, crucially, as an organiser of sound. His reputation as a producer/engineer was made.

THE UPSETTER, THE TUFF GONG AND THE ROOTS OF DUB

BETWEEN 1968 and 1974–the period in which another bout of vinyl revenge gained him The Upsetter handle – Perry worked incessantly. In this country his productions were issued on dozens of labels. Over 100 cuts, often spiky instrumentals, were issued as singles on Trojan’s ‘Upsetter’ subsidiary. Some, like ‘The Return Of Django’, were even pop hits. And it was during this maelstrom of creativity that he tapped the muse of Bob Marley and helped unleash dub on an unsuspecting world.

The Perry/Wailers union yielded two classic reggae albums (available currently as ‘Rasta Revolution’ and ‘African Herbsman’) and brought Marley, and to some extent Perry to the attention of Island Records supremo Chis Blackwell.

How did he partnership with the Honourable Marley come about? “The Wailers had worked with Coxson at Studio One but it had networked out. The group had split up and Bob had gone to America with Danny Simms to do the Johnny Nash thing. But Nash didn’t want to promote Bob, just to pick his mind. When he came back to Jamaica he asked me to work with him.

“I liked him as a person and so I said OK. To be honest, everytime we recorded together it was something magical, almost too powerful, too strong.

“We worked like brothers ‘til Chris Blackwell saw it was something great and came like a big hawk and grab Bob Marley up.”

Island’s signing of Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer was painful enough. Misery was heaped on woe for Perry when two of his house band, bassist Aston Barrett and brother drummer Canton went with them to form the new, self-contained Wailers.

“Was Bob who organised that, with Chris Blackwell’s money. They took away my musicians. But I don’t get vexed with Aston or Carlton because money talks very loud. Aston still checks me every day.”

Despite this wrench, Marley returned to Perry throughout the ‘70s, at times for advice, at times to collaborate (‘Jah Live’, ‘Punky Reggae Party’ and ‘Rastaman Live Up’). They were “more than friends, like brothers, a team”, but Marley’s death brought forth some very strange utterances from Perry, then at the height of his behavioural unpredictability, a bizarre cocktail of grief and bitterness. Looking back now, what did he feel about the Tuff Gong’s demise?

From under the boater, liquid brown eyes flash. “I felt nothing. Nothing at all. You see, before he died, I had had a message from Jah and I went to Bob’s Tuff Gong Studio to tell it to him. But at that time he was making the big money and he had no time to talk to Scratch. I went to tell him that he was going to die but he said that if Jah had a message for him, he would deliver it direct.”

You felt slighted? Humiliated? What? “I said ‘wow, no problem …‘ If he had listened to Scratch, the idiot, the shit, the madman, he wouldn’t have died.”

Perry puts his hands to his face, like he’s going to cry, then shakes himself out of it. “For what does it profit a man to gain the earth and lose his own fuckin’ soul?” A huge, tired, sigh.” But who’s to blame? Bob is gone, and I’m still here alive.”

There’s guilt and sorrow, pride and pain, in those words. A tragic, unsavoury, ending to one of music’s most satisfying and influential marriages.

At the same time as nursing Marley’s talent to shimmering, militant fruition, Scratch Perry was also starting to experiment with technical trickery and sound effects in his instrumental work. Along with Osborne Ruddock (King Tubby) he is credited with creating the musical mindscramble we now know as dub.

“To be fair and speak the truth, it wasn’t land Tubby who brought about dub, but I alone! In those days Tubby had a sound system and he wanted dubs for it from me. He’d come to Randy’s studio where I worked at the time and spend days watching me messing about with the controls. As my dubs got famous and people like them, so Tubby try mixing up a few sides of his own.”

Now that, Lee, sounds like a likely story. Still, how had the idea of dub come about in the first place? “We liked to record the drums and bass first, to get them perfect. The other instruments would be put on afterwards. But sometimes the rhythm track would be so fucking perfect that we’d forget about the other parts and just play about with the drum and bass.”

“So what started as a technical thing became a creative thing. I’m so good at it because I’ve got great ears!”

BLACK ARK, GOLDEN YEARS

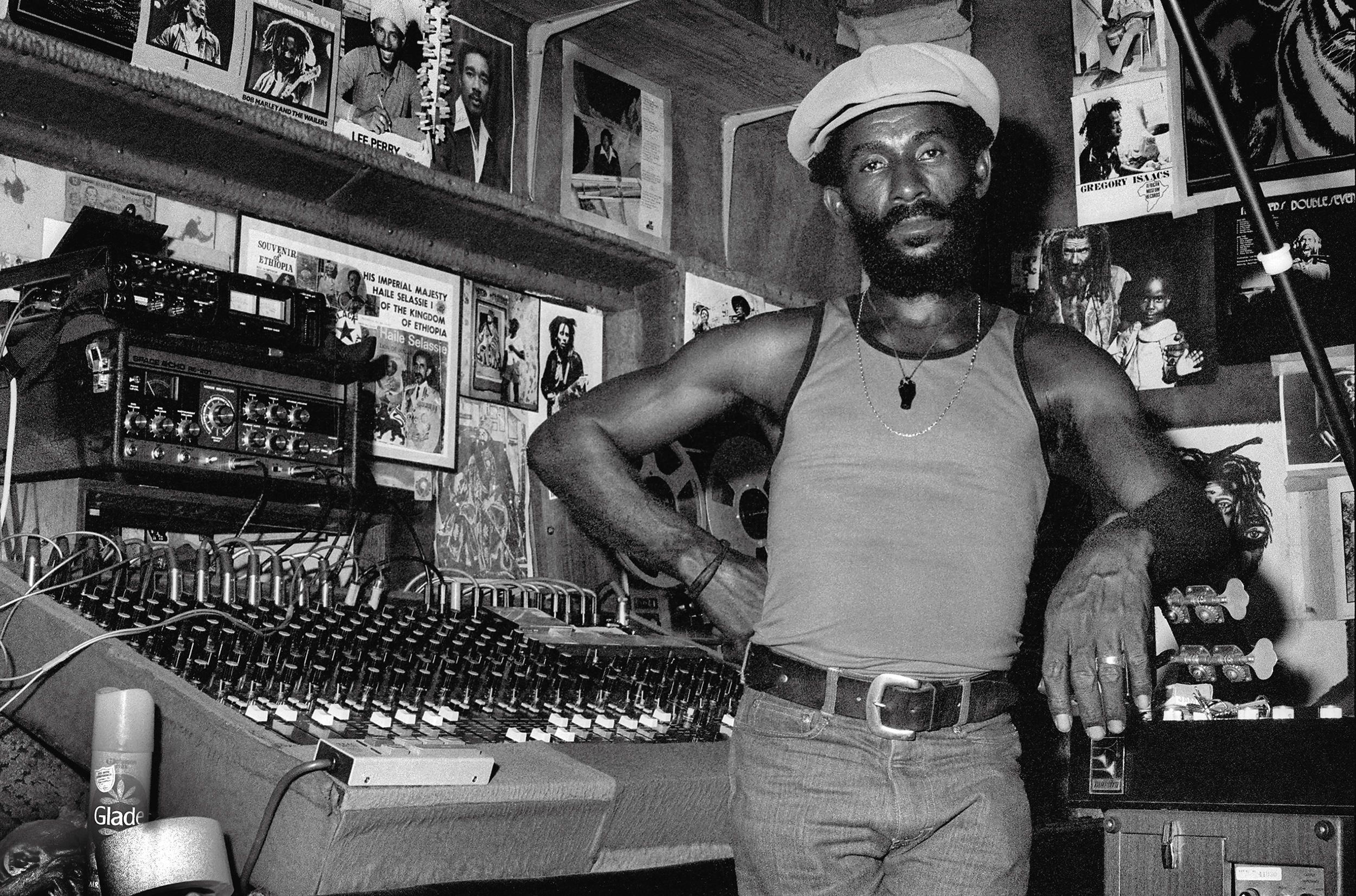

BY 1974, Perry had accrued enough money to open his own studio and record label. Based primarily at the bottom of his garden, he called his studio the Black Ark.

A claustrophobic four track set-up, it was from here that for six years welters of the best reggae, of the best music ever made, sprang. Scratch, barefoot, in shorts, a spliff ever draped from the corner of his mouth, would skip, hop and whirl, and move his hands over the console like a spell caster or a faithhealer. And onto the cold tape would fall showers of magic.

The sound achieved in the Ark was unique. The music was springy and light, as though it had been dabbed gently onto the vinyl, like kisses. At a time when other studios were making passable dub impressions of steamhammers getting to work on massive chunks of concrete, the Ark dubs were often spidery constructions of lacy delicacy. Some, like the dub of Keith Rowe’s ‘Groovy Situation’ were

ethereal, threatening to evaporate before the needle reached the run-off. Others, Murvin’s Crossover’ for instance, were demented soundscapes like none heard before, and seldom since. Almost all this music was brilliant.

And, in a genre dominated by 45s, Perry forged classic albums: dub ones by The Upsetters (‘Super Ape’ and its sequel ‘The Return.. .‘), and vocal ones by Max Romeo (‘War In A Babylon’), Junior Murvin (‘Police And Thieves’), George Faith (‘To Be A Lover’) and The Congoes (‘Heart Of The Congoes’). Almost as astonishing as the sheer volume of irresistible music that was emanating from Perry’s mind was its breadth.

The Congoes record, along with The Abyssinians’ ‘Forward On To Zion’, is the most uncompromisingly spiritual of popular reggae, while Faith’s disc focuses on the heart’s business and the messy pleasures of the flesh. Scratch finds no conflict in this.

“Most certainly not. God is sex! If there was no sex, we would die, and with us would die truth and religion. God loves sex.”

What kind of producer are you? “I expect artists to do exactly as I say. I teach them everything. How to play, how to move, everything. I am a dictator!”

There’s not much evidence of the dictators sound on the track he produced for The Clash. “That is true. But when I got involved with that record, most of it was already done. I liked The Clash, they were nice boys, I taught them to turn down their guitars in the studio.” He covers his ears. “They were loud, man, loud!”

And I notice, Mister Dictator, that none of your acts ever made a second album with you. “That was caused by the thief Blackwell”, he claims. “He never paid me for the way them records sell in Britain so I can never work again with them artists. cha… that man is a parasite..

MYSTERY AND THE LOST YEARS

PERRY NOW sees his black despair at what he regards as mistreatment by Island as the major cause of his seemingly inexplicable destruction of the Black Ark. Whether invented or real, his recollections of those desperate events are cut-glass clear. His account is given in a detached monotone, without traces of sadness or regret.

“For weeks and months the pressure had been building up. I was getting no money, just pressure, pressure, pressure. I got up that morning with turmoil in my heart and went to the bottom of my garden, the studio, y’know. I love kid’s rubber balls. They are air, trapped. I love that and I collect many of these balls. Anyway, I have one favourite, it came from America and I kept it on the mixing desk. Some one had taken it when I got to the studio and I was just filled with anger. First all the pressure, the thievery, and then this..

What did you do? “I destroyed the studio. I smashed it up and then I burnt it down. Over.” How did you feel the next day when you looked out and saw not a place of work but a heap of ashes?

“I felt I had done the manly thing, that I had stood up for what I believe in. I was cleansed and relieved. No one could rip me off any more. Not Chris Blackwell, not anybody.”

But, Lee, this does sound exactly like the actions of a madman, nothing more, nothing less.

“I was mad. In my heart. But not in my mind. I have never been physically mad.”

Taking the above events into account, that’s probably a statement open to serious questioning. My own feeling is that Perry, by societal norms never a candidate for Mr Sanity, probably did flip his lid and is now applying retrospective logic to this actions.

Those actions forced him into the wilderness for four long years, the prophet without honour in his own land, without a studio but with a reputation that precluded rehabilitation.

Whatever his mental state then or now, his loathing of Chris Blackwell has become an all-consuming motivational force. One of the reasons for Scratch’s re-emergence is a desire to play out his vendetta with Island.

“I was going to beat Blackwell up. I could, easily. But I have decided to bankrupt him instead, to see Island in the gutter and the vampire a pauper. Every time Island has a hit record, I will produce a better version of it. I will ruin that company!”

That could be a tall order, Island are a big business, with incredible facilities and acts like Black Uhuru. Perry’s voice cracks into a wild cackle. “Uhuru guru schmuru! I don’t care who they have, I will do it. That is definite, confident, without qualification.

“You know, that Chris Blackwell disgusts me, makes me want to vomit. He invited me to the opening of the Compass Point studio in Nassau and there I saw him drink the blood of a freshly killed chicken. He thought I was into all that voodoo and obeah (African magic for inflicting damage on enemies, much feared in the Caribbean) stuff, and offered me some. It was disgusting.”

I hate to be a contradictory cuss, but we are talking about the same Chris Blackwell aren’t we, y’know, the internationally-respected business man? “Yes, yes, yes!” The knotty dubmaster is insistent. “I, Lee Perry, will swear that before any judge, solicitor or barrister he could employ.”

There you have it, Perry’s side of the story. A further illustration of the depth (again the bounds of rationality are being stretched) of his disaffection with Island is illustrated by the fact that he turned down the opportunity to produce no less a mob than Talking Heads, despite talking to David Byrne in a big way, because he thought that the Heads were on the label, instead of just using the Compass Point facility.

The Lost Years, a sad and tragic waste.

PROPHESY

So what of the future? In Perry’s favour there is at least a stability in his home life. He lives in Kingston with his three grown up offspring, a car and two video players. He has spent the dark ages writing – “on books, walls, stones, anywhere” – and exercising – “exercise and Buddah, that’s my recipe”. He seems to have his once monumental drink problem under control. What about drugs?

“If I take drugs I will be unfit and unable to speak to the people because when I speak, it would be the drugs talking. But I will take herb from morning ‘til night. I will smoke it, eat it and drink it! But cocaine is bad for the body, and I love my body!”The Upsetter, in his own highly unqualified opinion, has never been in better physical fettle and, his ridiculous and ugly plan to deal with Island notwithstanding, is ready to record again.

Plans are afoot for the building of a new studio on the site of the Black Ark and he’s working with–and here’s one for your scrapbook– Linda McCartney on a project started many years ago but that was stalled by the Perry problems. In London this month he has recorded with Neil Fraser, the engineer at Ariwa studios whose work as the Mad Professor has established him as the British reggae producer. This is a master/apprentice relationship as fascinating in prospect as watching Method babies De Niro, Pacino and Duvall kneel at the feet of Papa Brando in The Godfather.Listening to Perry talking about his schemes and knowing the, ahem, unpredictability, of his past, it’s hard to be anything but sceptical, but Neil Fraser, as sane as his records are loonie, is a reassuring voice amidst the doubts.

“The little bits of work we have done have been really fantastic. The man is back and doing it. I think he’s ready.” So convinced is Fraser of this that he’s now slated in for mixing desk duty when Perry takes to Britain’s halls in the near future. He will be using for backing “any musicians who know the musical scale of ‘doh ray me’, I will teach them everything else!”

And finally, ‘History, Mystery, Prophesy’ will very soon be released on Seven Leaves in this country. It’s not a great record but a couple of the cuts (‘M Music’ and ‘Heads Of Government’) are vintage Scratch. And nobody else would dare rhyme “Martin Luther” with “computer”, would they?

The ball is in motion but it really is too early to say whether this dotty, angry, electrified bundle of creativity, a man not really with us half the time, can complete what would be a remarkable comeback, second coming. He won’t fail for lack of confidence.

“I am the best record producer that Jamaica has seen. Many say that l am the best in the world!!”

From the shambles of a brilliant, wasteful, bitter and possibly insane past, Scratch may still be genius enough to prove that. For people like myself that have lusted after his work there is the comforting thought that where there’s life….

[:]