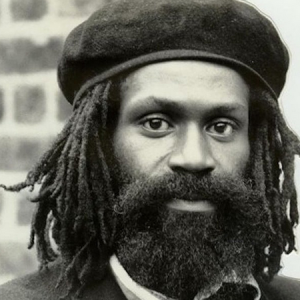

Interview with Jah Shaka

In 1989 Shaka visited Jamaica and worked with many musicians there, including King Tubby. In 2002 Jah Shaka appeared before a large crowd in New York City’s Central Park. Live footage of Shaka is featured in the documentary All Tomorrow’s Parties based on the musical festival, which was released in 2009. The Jah Shaka Sound System continues to appear regularly in London, with occasional tours of the United States, Europe and Japan. On his own record label he has released music from Jamaican artists such as Max Romeo, Johnny Clarke, Bim Sherman and Prince Alla as well as UK groups such as Aswad and Dread & Fred. He has released a number of dub albums, often under the Commandments of Dub banner. Shaka’s uncompromising “Warrior Style” has inspired a host of new UK reggae artists and Sound Systems such as Eastern Sher, The Disciples, Iration Steppas, Jah Warrior, Channel One Sound System, Conscious Sounds, The Rootsman, Aba Shanti-I and Zion Train.

Jah Shaka events are renowned for attracting a wide audience from all backgrounds, races and ages. His dances attract numbers previously thought unthinkable for this genre of music. Shaka believes it to be a testament to the quality of the message that he expounds in his choice of music and his Rastafarian beliefs. His followers are known to be vocally ardent, and have developed dance steps that resemble African war dances.

Jah Shaka’s music has had a profound influence on genres in the UK like Junglist, a ghetto style born out of the UK soundsystem culture. Jah Shaka’s son Young Warrior has now started his own sound system, to great acclaim.Drum and Bass is also deeply influenced by Jah Shaka’s sound system frequencies, and a number of the DJ’s who feature in that genre, such as Congo Natty frequently name check Shaka’s sound.Don Letts has also frequently referenced the influence of Jah Shaka on John Lydon and on the punk scene as a whole.

Interview by Steve Mosco with Jah Shaka in 1984.

https://www.dubclub.nl/shaka2/interview/jwshaka.htm

Steve Mosco: How long has the sound been going?

Jah Shaka:Since 1970.

Steve Mosco: When you started the sound, was it your intention for it to be the same way it is now – a rasta dub sound?

Jah Shaka: Yes, it was always a dub sound. The sound came out of the struggle in the 70’s which black people were going through in this country – we got together and decided that the sound should play a main part in black people’s rights & we would work hard at it & promote some better mental purpose within the black race.

Steve Mosco: There wasn’t much dub around in 1970 was there? It only started happening a few years after that didn’t it?

Jah Shaka: Well I had dubs at that time. I used to get a few from Jamaica, and what we couldn’t get we made ourselves. We had a lot of musicians creating stuff for us.

Steve Mosco: The music changed a lot in the early 70s – the sound of it with people like King Tubbys & also it changed spiritually – why do you think that was?

Jah Shaka:The spiritual concept was people remembering their past – this kept coming into the music – as people remembered their history it was repeated on record to make the rest of the nation aware what had happened.

Steve Mosco: The music got a lot heavier then too – was that a conscious idea?

Jah Shaka:Yes, because originally the bass drum came from Africa, so that downbeat sound became present in the music – at one time reggae was copied from English records or American hits, just to reproduce them, and it didn’t have any bongos in, but now all that’s changed.

Steve Mosco: You’ve been doing a lot of recording in the past few years. Does that mean you can’t spend as much time with the sound as you used to?

Jah Shaka: Well the whole concept of sound systems now has changed since I first came into the business. It’s become a gimmick now with certain people, so I prefer to have that orthodox discipline about sound system – then you won’t get involved so much in the commercial side of things – it’s only certain people that want to book this sound, knowing the type of music we play. I’m not playing on a commercial basis.

Steve Mosco: Is what you’re doing strictly a message or is it entertainment as well?

Jah Shaka:Message & entertainment. Music is the only language which everyone can understand, so the message is being carried out but people also enjoy the music because of the beat – even if they can’t understand the words they get into the beat.

Steve Mosco: What do you see the future of Shaka sound being?

Jah Shaka:Well right from the start my ambition was to play to the people of Africa, so eventually we hope to put on a reggae show in Africa, with a band as well. We’re hoping to change a few things and get people to open their minds.

Steve Mosco: It’s kind of strange that the music you play comes from Africa yet most people in Africa haven’t heard much reggae.

Jah Shaka: No, they’re waiting very patiently to hear it. Now and again promoters bring records to these places and bring bands too, but sometimes things go wrong because there’s so much intercontinental arrangements to make, so things are a bit fifty-fifty on that side. But they’re definitely wanting to hear reggae more fully.

Steve Mosco: I’ve heard it said that you don’t really go in for competitions, yet you’ve always been rated as the number one for years now.

Jah Shaka: Yeah. You know the concept of this sound is a different thing. I don’t know what concept most sounds are built from, but we had that concept from the start & we have to see it through, whatever it takes, so if it takes the sound to play by itself to achieve that, then that’s what I’d rather do.

Steve Mosco: Why do you think most people follow you – aside from the spiritual thing, there must be something about the way you sound – why do you think most people respect you?

Jah Shaka: Well we’ve always tried to fulfil what we’ve said our aim is – we’ve always stated these things and people are aware of it, so that concept is spreading. It goes further than the sound system, because the music is a stepping stone to get the message across. We hope that not only black people but also people of other countries can enjoy it and listen to what we’ve got to say.

Steve Mosco: In the past few years there’s been an effort made by some people to push reggae to an international audience, but do you think that would be impossible to achieve because of the subject matter it covers?

Jah Shaka: Well what I’d say to that is that when you have an olympic race and someone wins the 400 metres, it doesn’t mean that person is the fastest runner in the world. There could be someone else even faster who nobody knows about. Some people have to run for their food, but those people don’t have the contacts to reach these races. A lot of people today are making music which doesn’t get promoted outside of sound systems, which are the main reggae media, because before any radio stations played reggae, we were promoting groups like the Abyssinians, Burning Spear, etc. Well now, people who search within the business know of these names, but not everyone. These are the artists who paved the way, but they get pushed in the background, and the new people who are making stuff don’t get promoted properly. So regardless of how far reggae is reaching, you’d have to have a radio station to let people know what’s going on, not just two hours here and two hours there.

Steve Mosco: Reggae is an underground music even in Jamaica, because you hardly have any reggae played on the radio in Jamaica.

Jah Shaka:Well yes, that’s worth talking about – certain types of music get pushed and certain types get left behind, and that’s totally wrong. So that’s why our sound plays the people who don’t get promotion.

Steve Mosco: How would you describe the effect dub has on you?

Jah Shaka:Well, because I’m a musician there are certain things I’m looking for before it’s even played. Some people might dream mentally, but I get my dreams through my ears, so therefore I expect certain things and when I hear it I know it. That’s the kind of music we play – which reaches the heart – really it’s a heartbeat music.

Steve Mosco: Could you describe what that feeling is? I’ve seen you at dances where you go into a trance, and people in the crowd too – it obviously goes beyond entertainment and into a different kind of vibe altogether.

Jah Shaka:Well… that’s the force of music. We give thanks to His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie to be able to do that, because in the beginning was the word, and we have to put the word across, so we give all the praises to God… music is feelings no matter where it’s played. Some people say that it isn’t proper music if it isn’t played in Jamaica, but then you’d have to say that no one can feel anything unless they’re in Jamaica. God has created certain things and these things appear to you at certain times when the music is played at the right time…. it’s a feeling created by God himself.

Steve Mosco: In a session where you’re playing on your own, which could be for 8 or 9 hours, is there a conscious attempt to build up the vibes as the night progresses?

Jah Shaka: You can’t come out and plan to play a certain record, because God has inspired me to do what I’m doing, so I just have to go with the feeling at the time. I might play one record which then inspires me at that moment to play another to follow it, and so on.

Steve Mosco: Returning to the subject of competition, If you were playing with another sound and you each wanted to prove yourselves, how would you go about it?

Jah Shaka:Well the whole sound system business has really got out of hand because of those things, even the whole reggae business. When I first started the sound and was playing with people like Sufferer, people just wanted to enjoy themselves – you’d get someone from the other sound coming up and offering to buy you a drink, but then it got to the stage where people started to change the way they played. Instead of playing to please their crowd, which I still do, they said they were coming to take on the next sound in a clash, and it might have brought a big crowd – they might have brought 200 people and I might have brought 200 people, but at the end of the night there was too much talking on the microphone and not enough records played and the crowd went home disappointed. Well this is not our aim so we prefer to totally avoid that. I’m not looking to prove anything, all I want to do is get across to the people. Plus you could spend a lot of money to play in a competition and at the end of the night you might not even get a quarter of that money back, and that doesn’t make sense. People shaking your hand and saying you’re very good and you’ve got a load of cups, but you’ve got no money, and you’re the one that’s doing the work, so these aspects have to be looked at carefully.

Steve Mosco: You’re also quite unusual in that you’re pretty much a one man show – operator & dj. Did you always intend to do this?

Jah Shaka:Not directly, but it just happened that it worked out that way throughout the years. There’ve been times when we did have a lot of djs, but because of our orthodox style, now there’s not many djs who would step forward and ask for the mic, knowing what our style is. It’s a different set up completely from most sounds.

Steve Mosco: You appeared in a scene in the film “Babylon” which portrayed a sound clash which was getting quite fierce and almost led to a fight.

Jah Shaka: Well that’s the impression that the people who made the film had about sound systems, which they’d heard about from the competitions. They gave me a script at first and when I read it I refused to do what they wanted. I ended up directing the scene I appeared in myself, because all the build up leading up to it, with people from my sound confronting another sound, well that just doesn’t go on. We’ve got a very disciplined set of people, and I was totally against the way they portrayed the build up to the dance in that film.

Steve Mosco: Talking about the technical side of your sound now, you’ve always been noted for the effects like syndrum & siren, etc. When did you first get the idea to use them?

Jah Shaka:Well I’ve always had some kind of sound effects, not to this level, but over the years it builds up where you want more and more. In fact I was thinking about getting a set of four syndrums, because new things are being built now. The more you can put into the music, the better it will be. In Africa you might have 200 people drumming all at the same time, and dancing. Certain sounds I use, I don’t know whether people have picked this up, but they’re really sounds of the jungle, like birds and noises you would hear in the wilderness.

Steve Mosco: These effects are examples of western technology. How do you see them fitting in to Reggae?

Jah Shaka: Well that’s what I’m saying – unless you can get 200 people to make these noises, you have to find electronic gadgets which can do it. If we were recording in Africa then maybe we could get 200 people to play drums, but until then we have to make do with other things. But there’s nothing which says that Rastas shouldn’t use technology. We need planes, ships and all these things.

Steve Mosco: The world is in a pretty bad shape at the moment. There’s even a military dictatorship in Ethiopia. Do you think your music can have an effect on the way things are at all?

Jah Shaka: I would like to think so. Historically the conflicts have all started in the East and most of them have been caused by colonialism. Now people are saying that they don’t want to be colonised and are rebelling against their rulers. But we Rastas have no fear of these things. We’re just passing through this place where we’re living temporarily on our way home. And the knowledge which we’ve gained in whatever country we’ve been living, we’ll take it back to Africa with us and use it to build up our own country there. I don’t think we’re asking too much to do that, and it’s not a problem for anyone if we do that. People are starving there and the only thing the world has done is to build nuclear weapons, so we have to help them ourselves. We will not stay here and suffer brutality, with no rights to express ourselves – if you’re a black person with a small business it gets shut down or something else happens, and people have talked about this for years but what has been done? We don’t want to fight in a country which doesn’t belong to us, and we Rastas are peaceful people, so we prefer to leave this place.

2014, interview by Benji B for Red Bull Academy

https://www.redbullmusicacademy.com/lectures/jah-shaka-tokyo-2014

Benji B:For people in the room that aren’t familiar with yourself or what you do, could you introduce yourself please and describe what you do in soundsystems? Jah Shaka: This is Jah Shaka, spiritual soundsystem, playing spiritual music from in the ‘60s in England, where there was a lot of difficulty with people arriving from the Caribbean. The music was the thing that kept people together because when the people left Africa to go to Jamaica and the Caribbean, all they could bring is their songs and their music. They weren’t able to bring things with them on a slave ship. They were unable. All they had was songs and memories of home. So over the years, the music has kept the people together. In the ‘50s and ‘60s in London, there were house parties, parties in rooms, 50-60 people. There were only what we call record players. It kept the people together and let families know other families, which was very important at that time because the people were segregated. When the black people arrived in England in those days, the difficulty was even to get a room. To get somewhere to live was very difficult. So you had to be very skilful. The nurses came from the Caribbean and helped the UK system. The people working in the hospitals, nurses and people like that and doctors, came from the Caribbean to help their families left in Jamaica and left in the Caribbean. That was the reason for people to come to the UK and other countries, to better themselves and to make sure that the people left behind in the Caribbean – that’s the only kind of insurance the families had in those countries, were the people and the families that went abroad. Some people went to Canada. Some people went to America and were able to have jobs. So over the period of time, the music is the thing that all the people had because it was very difficult for them in the early days.

Benji B: When was the first time that you were enchanted by a soundsystem, and when was the first time you were allowed to touch one?

Jah Shaka: I would speak, I think, before that. I don’t know about the schools in Japan but the schools in England said, “Don’t bring toys to school. No toys to school.” But I got a gift of a mouth organ. I had it in my pocket and I used to take it out in the school, but it was forbidden [to have] toys. So the teacher said, “You know that you’re not supposed to have this – but can you play?” I said, “Yes, I can play.” “Stop the class. Everybody stop. He’s going to play.” So I had to play. That was my first idea that you could entertain people because at the end of me playing, the crowd clapped. So that will bring us to entertainment. Very early, there was a soundsystem named Freddie Cloudburst in south-east London which was very close to us. At that time, no children or young person [was] allowed to touch equipment. No touch. Because of that and we looking after [the] equipment, polish[ing], the owner of equipment say, “Play records.” So people said I can play. But that crowd at that time were older people. We were young and we are playing to people 50, 60 years old. So we had to know what kind of record to play for older people, not young. Old. Going through that training with Freddie Cloudburst, it served a purpose for us.

Benji B :What kind of records did you have to play for them at that time?

Jah Shaka: All kinds of… you got Nina Simone. You got Tamla Motown with Diana Ross. You got the Temptations. You got groups like the Drifters and people like this in the early days of England, because they didn’t start to make Jamaican music yet at that time. So we were collecting music from America. And the people in Jamaica were listening songs from America. Only one station in Jamaica, Rediffusion, so the people were listening to music from America and getting inspiration to do music in Jamaica. At that time, only one radio station to listen to music. So people were glad that some people like Studio One and other studios were able to provide equipment for singers and musicians to come and play. Hence, you have a school in Jamaica, the name is Alpha Boys’ School in Jamaica, where a lot of legendary musicians, they grew up in the Alpha Boys’ School. That school was run by a lady named Sister Ignatius, it was a Catholic school. The Catholic people decided to let the children get instruments to learn to play music. You have many great musicians what came up through Alpha, like Tommy McCook, Augustus Pablo and many more people that grew up in Alpha Boys’ School in Jamaica. Listening to American music and English music inspired people to say, “My friend can make music. He’s good singer.” Your friend will say, “Oh, you can sing. You’re good.” And you try to go to studio to put your feelings from the heart. Many songs at that time came from within a soul, within a heart, because it was very important time for our people.

Benji B :Can you talk to us about the concept of soundsystem, having a soundsystem, and a little bit about the hierarchy within the soundsystem – starting off as a box boy and then learning the equipment and making the equipment?

Jah Shaka: As I said, we came through Freddie Cloudburst soundsystem. After that time, we decided to have a soundsystem for ourself which, in that time, because of the difficulty of black people coming to London or coming to England, we had to have something to bring message to people. Therefore, many people at that time were in Black Power, which someone called Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Angela Davis, and other great people were sending messages for the people to be united around the world. Therefore, this transpired to come to London where many people were feeling the pain of suffering, not good jobs, not being able to make money, very difficult. These messages from these great leaders like Malcolm X or Martin Luther King and such forth gave the people hope. Hope was very important because nothing else was there. You had to only hope for the future and pray for the people, for the future. A very difficult time for our people. Because of this, in those days, because of Black Power, the soundsystem was formed [as] a vehicle for the message. To bring message of peace. To bring people together. You have great leaders, national heroes in Jamaica. I’m sure you have heard of Marcus Garvey, a great leader in Jamaica, [he] would also bring messages to the people. These people are very important. That’s how they become national heroes, because [of] what they stood for, what they believed in, and what they lived by. Therefore, these things have been handed down that some people will carry on the work. Like for instance, if I come next year, this person might be Minister of Trade. This person might be manager of company, because when you practise something, eventually it will reach somewhere. You set high targets that if you miss, you are still somewhere. You set high targets and if you don’t hit center, you’re still somewhere. This is important. Many messages, like from Martin Luther King and these people, were sown amongst our people for some other person to take the message onto further level. The music helped to do that.In Poland, the Freedom Party, their messages were spread by reggae. In Poland, the Freedom Party, [there were] messages to help freedom fighters, reggae music. When Bob Marley went to Zimbabwe for independence, [it was] reggae music. It’s very important messages, and also the music helped vocabulary, words. People learned to speak English by listening to music. They learned words. I’ve been in Ghana before. Someone I meet can sing “One Love” by Bob Marley, but can’t speak English. They can sing that song but can’t speak English. When the song is finished, they can’t speak. They learned to speak English around the world through the music. So it is important not just to dance, but to listen to message. Message is very important to spread amongst the people. I say again, we plant the seeds that it will grow, because you have professors in England and around the world studying about music, what it does for people. Professors in university in England study about music, where it came from. During the studies of the professors that study about music, they want to find out origin of music. When they check all the records to find out, they go back to Africa with the drum. The drum. The Indians used to send smoke signal for message. Someone on a mountain could see message. In Africa, drum is used to send message. The drum speaks. When the professors check everything, they find out the music and the beat from Africa very important. The professors have said this, not just I, studies about culture, about where people come from. Give thanks.

Benji B: You’re considered very much the father of soundsystems in the UK, certainly dub reggae soundsystems, and have gone onto influence so many more. What was the moment where you first started your own sound and, furthermore, how did you find your own musical direction? Because you’ve stayed very firmly true to the dub reggae sound, all the way through the ‘70s, ‘80s, ‘90s, to the present day. What was the moment that made you realize that that was the message that you wanted to spread?

Jah Shaka:From early childhood, I played as a musician. We play instruments. From school we are playing the drums. We are playing guitar. We are playing keyboards. Then, you have a part when our parents were in churches in England. Many churches had bands, with choir singing, band playing in the churches. In fact, one of the churches in south-east London was formed in my mother’s house. So we had a early insight of the church. We became very thoughtful about what God wants us to do. What difference can we make in the world today? We decided at that time, through the movement of the Fasimbas [black political organization] in London, that this would be a way to spread a message to enlighten, to give people more knowledge, because we still see that they say people have five senses. Five senses, they have said. But we think that there is two more senses, which will make seven. Telepathy, where you spread message from mind, and you have intuition. Intuition is you can see far away. Intuition and telepathy will develop your mind. Like for instance, some of the people here would have heard about Beethoven or Mozart or Bach or Tchaikovsky. These are early musicians who write music, written music. Beethoven, they write music. But sometime in Jamaica and in England, people don’t write. They play from memory, from memory. When a band is on the stage to play, you hear the drummer say, “One, two, one, two, three.” No sheet, no read, no read, no sheet. Memory training very important. Practice, preparation, very important things.In the early days, we had ideas of earlier sounds, coming from Jamaican soundsystems, coming from Jamaica to England, and records coming. We had ideas and, because of the topics of freedom of the people, we made certain design. So in the early days, if you had some equipment, it wouldn’t be the same as this person equipment or that person equipment, because you had your preference to how you want it to sound. You had some expert builders of amplifiers because it wasn’t bought in shops. These were built by friends or companions, or close people put you in touch with somebody that could build an amplifier. After the amplifier was built, you had to explain to the builder or engineer what you want to sound like. Do you want your bass here? Do you want your bass there? Do you want your treble here or here or do you want your mid-range here? You had to explain your preference. That made the early days of soundsystems… each soundsystem was unique. Nowadays, the soundsystems, some amplifiers are bought in shops and it is not custom. So it’s difficult for them to change the equipment. But in the early days, engineers were available, great engineers, to make things that you could tell them, “I want this. I want this. I want it to sound like this.” As I explained before, practising and testing over the years and collecting information and listening to sounds, different sounds, and being a musician. I would explain now to many people that are in Logic and [their] computer making music, it’s very important to know about true sound. When I say true sound, I mean, a drum – what is the real sound of a drum? You have to have the idea of what is a real drum. Although you’re using a computer, you want it to sound real. Therefore, some people will sample real instruments into their computer, real bass drum, real hi-hat, real guitar sample, so when you play your computer, you will get a more true sound. Because the computer is made with certain sounds in it, but to get true sound, you have to adjust. You have to adjust it to get a real sound. There was an interview with Family Man, who is the bass man for The Wailers, which is a friend of mine also. It’s on the internet, they ask him, “What information would you give to people coming into music now to tell the youth? What would you tell them?” Family Man, bass man from The Wailers, said, “Tell them to study music from the ‘50s and ‘60s and study analog before digital. Study analog.” Family Man says study analog to know about sound, to study about true sound, analog sound. Then when you go onto digital, you have more of an idea. You have more of an idea how to tune your computer for it to sound more real, because not everybody can afford to go to a studio like Red Bull studio. It would cost a lot of money in England for a musician to book this studio. So many people try to make music on their laptop or on their computers. They try to make music about this. So it’s important to learn about analog as well as learning about computer. And when you link the two of them, good sound.

Benji B: Talking of making the most of what you have, can you talk to us about the modifications that you used to make to your amplifiers? What kind of things would you do to make the most of the equipment you had?

Jah Shaka: In the early days, the equipment was very small. We depended more on frequency, not power – frequencies, frequency. We depended more on frequency than the power because the power will only amplify your frequency. Therefore we try to get the frequency of the bass and these things working properly. Again, I speak about the professor at Cambridge University, study about music. He go to many parties, many festival with meter to check decibel, decibel meter, to study about sound. The professor’s conclusion was that bass help the human body bowels, the bowels of the human body. Bass can help the bowels of the body. Not Shaka say, professor say. (Laughter) Shaka only repeat. Not Shaka say, professor. Bass is good for your system, your digestive system.Also you have people in car crash, in hospital, can’t speak, coma. They call it a coma. They bring iPod, cassette, put music in their ears in hospital bed. They recover, regain senses. Music also is a therapy for people, the human body. There’s elements of music which is like nature for the people. These elements are very important as well, to get these elements into your music when you are making your music, that other people can feel, not just hear. Feel, hear, heart, and feel the beat and then acknowledge what the music is about, what the music does for you. Those things are very important to us.

Benji B: Can you expand a bit on the difference between volume and frequency, because I feel like that’s an important part of the science of what you do, the difference between having loud bass and the right frequency of bass?

Jah Shaka: It’s very difficult to explain. Some bass is very loud, so people (clutching his ear), too loud. Some bass is hertz. Hertz means like rumbling but you don’t hear. It’s very low frequency. Hertz is very, very low frequency. So we try to play the low frequency, which some people think is volume but it’s not volume, it’s a frequency. It would be hard to explain unless you have some equipment where we could show the people what we are talking about. Frequency is whether it’s in mid-range or whether it’s a treble, the frequency is different. For instance then, this cartridge is a magnetic. If you were playing a record now and you take out this cartridge and put a ceramic needle, it’s a different frequency. Still play the record but completely different frequency. So it might be you’d have to adjust this different when you change this needle. It’s adjustment sometimes and what you need to get. People need to study frequency.

Benji B: With that in mind, do you find it difficult when you travel to play on sound systems that aren’t your own soundsystem?Jah Shaka: Sometimes, but we try our best to do what we have. Sometimes. But we give thanks because some people are only learning. Yeah, so after we leave, they learn a bit more. Next time it’s a bit better. Next time a bit better. We explain and advise.

Benji B: Obviously you’re known very well as a DJ, but what was the moment that made you decide to start creating music as a musician yourself?

Jah Shaka: In the ‘80s there was a time when oil was not so prevalent like now. Oil. In Jamaica, there was a period in the ‘80s and ‘70s where no pressing in Jamaica, vinyl was very scarce. People had to regenerate old stuff to make stuff. There was a time – in fact Bunny Wailer made a record, “Arab Oil Weapon,” because of those times. There was no oil for other people. So we started to put trumpets, saxophone onto old music to be something different at that time, to do different things. Because for one year, no records from Jamaica. You had to make your own records. You wanted something different than other sounds.Because soundsystem at that time was very competitive.

Benji B: Tell me about that competition. Tell me about the legendary Shaka and Coxsone [Dodd] clashes.

Jah Shaka: You have all these soundsystems and on the night, everybody want to come out on top of a certain gig. Everybody wants to be on top. We didn’t really enter as clashes really, but the people, when they want to take you on you had to defend yourself. All those soundsystem know that Shaka comes with a message. All of those soundsystems, they know that. Shaka is a message of Rastafari, a message of Jah, a message of goodwill, righteousness, trustworthy, dignity, integrity. They know what we stand for. Shaka sound is built on a principle, not just equipment, principle. They know about Shaka principle. So some people don’t try to clash because we have our principle and we have many supporters over the years, because of the principles what we stand by, how we live.

Benji B: Talking of film, do you mind if I play a clip from Babylon? Because that was the first time that your system appeared on camera right? Officially. Can you just give us some context on what was Babylon? It was a 1981 film.

Jah Shaka: Yeah, 1981.Really the stories, our story really, but the people that lived nearby us saw things that we had done and was able to, [because] they live in the same area, to put something like this together. The whole story is really Shaka’s story. Is really Shaka’s story, really.That was Brinsley, the other co-star, from Aswad, and myself in the film Babylon from ‘81.

Benji B: a crucial part of the experience obviously is the mad echo, obviously is the delay, obviously is the reverb, and obviously is the mic. But a huge part of it is a siren that has almost become officially known as the Shaka siren. I thought maybe you could just explain how that came about, how that became such a significant signature of yours working with the siren and the delay, and now there’s even an iPad app that has the word Shaka on the siren.

Jah Shaka:Yeah, Apple has used our name on a product somehow. No, they didn’t ask. They seem to have sampled. No matter how many sirens have been made, ours is one of the unique sounds. Apple used that one in their program, on their apps. Other soundsystem over the years, many soundsystems, they have a siren like what they saw in the film. Because before this film, many people didn’t know about Shaka before this film. Although I had not met some people, they were able to see from this film equipment what we use. Over the years, it has been inspiring to know that other people have took note of what we were doing over the years and really carrying it on.

Benji B: When did you make your first siren box?

Jah Shaka: When we started. That was about ‘69.

Benji B: Are you feeding it into a delay and then another delay?

Jah Shaka: No, no, just straight into one delay. Normally we use a delay called H&H but it’s very difficult to get it because it runs on a tape loop, not digital. It’s an analog set up so it’s very difficult to get now. It’s like antique, an H&H echo chamber. Maybe you can see it on the internet or things like that. That’s what we were using in that film.

Benji B: What else is in the stack? Tell us what’s in the Shaka stack.

Jah Shaka: You got the general pre-amp is the basic pre-amp, but you also have bass frequencies which you can adapt. Some people call it a parametric. We’ve got a parametric on the bass and a parametric on the top. It’s just simple. It’s not so much things but it’s how you use it.

Benji B: Tell me about the science of how you set up the room? How do you tune a room? When you go on soundcheck and you put the Shaka soundsystem…

Jah Shaka: Like this place now, if you put some boxes there in that corner, there’s an acoustic according to the room. If your speaker was there, you would play it louder than putting it here because the shape of the room and the roof can… Even sometime, if you turn the speaker to the wall, you get more bass by rebound. Over years of studying, when you go into a place like this, you assess where is the best place to put speaker that the people, everyone can hear. We don’t play, like some soundsystem play, with a stack or two stack. We want surround sound, so it surround. Everybody can hear everything.

Benji B: Normally you have four?

Jah Shaka :Four. It’s normally four stacks.

Benji B: So wherever you’re standing…

Jah Shaka: Wherever you’re standing, you get the same sound. If you are playing there now with your amplifier and all your boxes are here, you will turn up more to hear it. That’s not good to us. We need monitor, to monitor the sound from there to here, to have an idea that all of them now will sound equal. That’s part of balance. I always talk about this turntable in this way because that turntable, Garrard, is built during the war time. Those turntable exist between 1945 and 1950.

Benji B: You’re still using that?

Jah Shaka: We’re still using Garrard, yeah. It’s very old. It’s like antique now. It costs a lot of money on the internet to get a turntable like that because it’s completely different. The arm is completely different from these. You don’t get that feedback to the arm because those turntables were built to play 78 records. You got these turntables on there (points to table), for 33 and 45, but the old Garrard is built for 78 records. Therefore, you got like Nina Simone, “My Baby Don’t Cares for Me,” and all those things on that, [Jesse Belvin’s] “Good Night My Love (Pleasant Dreams),” was originally on 78 records. The early sounds in England used to have to have Garrard, else they couldn’t play them. There were no records yet from Jamaica. But we found out about when you link it up with equipment, it gives it less feedback than any turntable in the world.

Benji B: So you don’t need to isolate it from the…

Jah Shaka: Not so much, no, like other turntables. That’s the reason why we still use it.

Benji B: And the syndrum?

Jah Shaka: Yeah, that’s very important because other people have taken it like the siren but we actually play it like you saw in Babylon film. That was another iconic thing that people saw with us. So we try to develop new things and people see. We test lots of things what we haven’t even used yet, but we test things to know, does it sound good? Test. Test. Test. Lots of different things we test to get right sound.

Benji B: With the vintage and that more archive, old-school equipment, are you still using that because it’s what you know, or are you only using it because you haven’t heard anything that sounds as good?

Jah Shaka: If we make new amplifiers now, it has to be on a par with the old ones because the pre-amp is built to deliver a certain punch. We can use valve amplifiers, build a transistor amplifier to be able to sound like it, because you got an idea what type of sound you want to get. Therefore we can put things in the amplifier on the driving stage to give it a definite sound. So when you turn up, that is the sound you will get. Don’t change. There’s a set frequency which, once we’ve got it, we leave. We don’t keep turning, turning. We leave that frequency there and the treble frequency and mid-range frequency the same. Actually, you can play any record like that. Sometime you might need a little more treble or a little more bass, according to the record. Some records are made on reissued vinyl. Sometimes the quality is not excellent so you have to have a good pre-amp. In the early days, people didn’t play Studio One records unless you had a good sound. Because the sound on it, the vinyl was crackling on the record (makes hissing sound). To get that out, the Garrard needle used on the Garrard, [there] was already equalization in the needle because of playing 78 record, to get that at that speed. The Garrard turntable was the best to play Studio One on, these early pressings, which were not of high quality.

Benji B: With that in mind, are there any selectors or sounds, young sounds, that you think are…?

Jah Shaka: We have a new generation of sounds, which play with my son and they play in England, like Iration Steppas and you have Earthquake, another soundsystem which is in that kind of genre, that kind of era. But a lot of the old soundsystems doesn’t really exist again. A lot of the old ones from the ‘60s. You had Duke Reid. You had Coxsone. You have Count Shelley. You have Sir Fanso. You have Fatman. You have Quaker City from Birmingham. A lot of good sounds which help their community at that time. As I was saying, the music was important to keep people together. So you had a lot of soundsystem were played for their people. If they were playing at the dance with you, they could have their friends and your friends would meet and sometime friendly. It depends between sound men because the sound people have control. If they don’t make noise on the microphone to each other, the people will be all right, if they are not against each other. If we should go in a dance and I say one love to the next sound and the sound said one love back, it would be a peaceful affair and you’re able to put over a message clearly because no preacher has ever been preaching in the church to give a sermon and be interrupted. So sometime if you know a lot of sound is making noise, we don’t really play with sound system, because we want the message to be very clear, so you don’t want too much diversion. Because, you know, some of the soundsystem are playing different type of music. Because we have got our topic from a long time, we continue that role. Jah has inspired us and he gave us this gift and we are honored to be able to play a role in the development of reggae and the development of a generation of people around the world. We are honored to be able.

Benji B: How long, as a DJ, how long as a selector would you play for, on average, on a Jah Shaka dance?

Jah Shaka: Sometimes eight, nine hours, sometimes. Sometimes 12. It depends. Sometimes you’re at festivals, big affairs where the people want us to play. The promoter might try to say, “Can you finish?” But the people say, “No, no, no. We want more. We want more.” We play for the people……….. because you’re always had – and people talk about this, because we promote – most of the labels that come out in the world that makes music which is our topic, about God, about his majesty, about truth and rights. We promote all these labels around the world. We do promotion for labels, not just Shaka music. We promote all these other labels. It’s a big list of labels that make roots music what fit our topic. The things I’m saying, there is music that is made. So sometime I look at it to say, the people have helped my subject by making these music. I can get them and put them into my sermon, my message what I’m putting over. So that’s a part of it, that the young youths get promotion. ……..Because when we started soundsystem, you must know that there was no radio station. Reggae was not being promoted on the radio like now. At that time, the only promotion you had was soundsystem and parties. That was the only way people would know the records from Jamaica. We’ve had many good friends over the years. Some are not with us now, like Gregory Isaacs, a good friend of mine. We were in Jamaica together. We were in London together. There is John Holt, a good friend of mine that maybe I can find a picture on the laptop to show you, John Holt and myself this year, Garance Festival. A lot of people have played a big part in reggae. Sugar Minott, people like this have played a big part. ……….

Benji B: This is kind of a delicate question but I wondered how yourself and the early British black community responded to white people wanting to integrate with your scene and from David Rodigan wanting to do his own soundsystem in Kingston and things like that. Did it flatter you or did you want to protect it?

Jah Shaka: You know that ska was a music that existed long time ago, the music of ska. One of the famous people in it was Prince Buster in Jamaica. Blue Beat Records. Prince Buster made “Judge Dread” and a lot of other songs. When he came to England, it was white people that met him, not black, at the airport. It was white people. We call them at that time skinheads. They wore small pork pie hats, Crombie coats, Doctor Marten boots. They were meeting Prince Buster. So you had a lot of people that recognized from ska music and came in. Even the punk music, they recognized it from the early ska. Many groups like Madness and all these groups that exist, they learned from reggae. UB40, all these big groups, their parents were playing records in parties for them to know, “Red, Red Wine,” all these songs. For them to know, their parents were playing them. I knew David Rodigan before he was famous. He used to come and listen to soundsystem. We are playing now for 49 years. That’s the length of time, nearly 50 years. Five decades. When Rodigan came, he saw us, sound systems, to know about music. He study about music and some early people in music business. Their names don’t come up often. John and Felicity Hassell. They used to cut dubplates on the machine in a place named Barnes in England. We used to meet David Rodigan there with these people. It was very tight community at that time in reggae. When you had somebody like [mastering engineer] John Hassell, a man named Graeme Goodall, and a man named [producer and arranger] Tony Ashfield, [who was] able to go to Jamaica and put strings, violins and things onto John Holt music. It’s an idea of some producers in London that were able to go to Jamaica with these ideas too. So the ideas still work and it’s carrying on, regardless of who, because the truth carries no color. The truth doesn’t have a color. It doesn’t matter who spoke the truth, it’s if it’s true, and your inside will say it’s true. There is no color barrier within our function in our playing of music. As you can see from some crowd, it’s mixed.

Benji B: Hi. I’m very moved with everything you’ve shared with us and I wanted to ask you about how your spiritual search has influenced your sound search? How frequencies and that kind of approach to your tools with which you work have informed you.

Jah Shaka: Well, as you have said in that word spiritual, spiritual around us and to accept spiritual understanding and put it into action, not just to know, to put it into action. The topic of Africa, the topic of the Almighty, the most high, Jah, Rastafari, these things are topics which we pass onto people which is very important to me. Rastafari is not just a religion, it’s a way of life. It’s a principle. It’s a way of living. The Bible says, “Do your work to let others see that that might glorify God.” Not the person, for we are just a tool. We are just a tool God uses to get to the people. All of us is tools. You have gifts and you have talent. It’s up to each person to investigate their talent and link it with the spiritual things in life. Link it with nature. Yeah, it’s very important. Nature is a very important subject to link music. It’s really a science to be able to receive message and transfer message to people. Receive, transfer. Spiritually, that is what gives us the inspiration and the knowledge and the understanding. You can know about the world, but to understand what the world means, it’s a different thing. It’s always investigation. Every day there is something to learn, each and every day, when you’re spiritually linked. Yeah, make sure your mind is clear that you can receive spiritual message to enlighten you, that you can make changes where changes are necessary. Thank you.

Benji B: I’ve always been interested in how, in hindsight, how easy it is to trace the lineage of reggae from (mimes fast drum beat) and then slowing it down to (slower drum beat) and so on. I was wondering, at the time, how conscious were you of that, and how much did you really see the development happening, or did it seem to arrive in its fully fledged form?

Jah Shaka: In the ‘60s, the music and lyrics were more dance. People were happy dancing. In the ‘70s, it became more message. In the ‘70s, people used to sing about what’s happening to them. Not American songs like you see on the radio and sing back. They used to sing about, “Yes, I met Tom yesterday.” They put that lyrics, or Gregory said, “I gave her the key to her front door.” Somebody like [inaudible] said yes, “I was there the day when you gave her the key.” It’s more reality music in the ‘70s. You have certain artists that come with messages like Burning Spear, coming from the north coast, like Twinkle Brothers. You have singers what are message singers and you have singers what sing reggae. So you have different branches of reggae, different branches. Now you have dancehall. Now you have bashment, but it’s a different branch. When you have a tree and you break off all the branches, break off all, the root is still there. The roots. Other things are there, but the root is dominant else you don’t have a tree if you don’t have a root. That’s where we are really, to make sure that we’re at the source, the source. Yeah, that’s where we stand. One love. Rastafari.[:]