Interview With Linton Kwesi Johnson

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2008/mar/08/featuresreviews.guardianreview11

Interview: Linton Kwesi Johnson

By Nicholas Wroe

Thirty years ago, it was not uncommon to encounter white, middle-class suburban and provincial teenagers wearing badges that proclaimed “SMASH THE SPG”. The primary spark for their opposition to the Metropolitan Police’s Special Patrol Group and its role in policing London’s immigrant communities came from the work of Linton Kwesi Johnson. When the SPG was eventually disbanded in 1986, it was under a deluge of public condemnation. It is not too outlandish to suggest that Johnson’s poetry and music shaped that opinion: so much for Auden’s claim that “poetry makes nothing happen”.

Johnson’s debut album, Dread Beat an’ Blood, was released in 1978. It comprised poetry written in an uncompromising Jamaican-London vernacular and militant politics set to a reggae accompaniment. The combination ensured that his vivid and angry stories of Brixton street life and police brutality broke out of their south London setting to acquire a resonance far beyond location or race. Follow-up albums Forces of Victory (1979), Bass Culture (1980) and Making History (1983) provided the soundtrack to a remarkable period of postwar history during which the children of the Windrush generation of Caribbean immigrants established their permanent place in British society.

His most famous words are: “England is a bitch “: a rant about racism then proclaimed that, in his view, England was still ‘a bitch’.” In any case, to focus on whether or not Johnson has earned the approval of either the political or cultural establishments is to miss the point. That they have taken note of him, he says, “is great. But they recognise me, not the other way round. Some black and Caribbean poets seek a kind of validation from these arbiters of British taste. But they really didn’t exist for me. I was coming from a position of cultural autonomy. I did my own thing, built my own audience and established my own base. My audience was ordinary people.”

Johnson was born in rural Jamaica in 1952 and was brought up by his grandmother after his parents separated. Their village had no streetlights, running water, radio, TV or newspapers, and he hardly ever saw a car. The hub of social life was the church, and his most memorable early reading was the Bible. “I would read the Old Testament and the Psalms to my grandmother, and that was my first introduction to written verse. People there know it, or at least bits of it, by heart. Illiterate people could quote from it and it was used in everyday conversation. You’d hear phrases like ‘the hotter the battle, the sweeter the victory’ all the time. At least half a dozen reggae songs use a variation on that line.” He left Jamaica aged 11, in 1963, to join his mother who had emigrated to London the year before. He experienced surprisingly little culture shock, but was taken aback by the “hostility to black people, particularly from my contemporaries at school. And also from some teachers who couldn’t hide their contempt. There were also some very kind and good teachers, but a few were real bastards.” There was some exposure to literature at school – “I remember The Caucasian Chalk Circle and Under Milk Wood” – but it was via a sixth-form debating society that he encountered Althea Jones of the Black Panther movement, “perhaps the most remarkable woman I’ve ever met”, which led him to attend Black Panther youth meetings. “She was a simply brilliant orator and a great teacher. That’s where I got my real education. A whole new world opened itself to me and I started reading all kinds of stuff. It was the formative period of my life.”

Under the influence of another political and cultural mentor, the publisher John La Rose, Johnson was introduced to African, Caribbean and American writers. “I discovered the Francophone poets such as Aimé Césaire and Léopold Senghor. I discovered Nicolás Guillén from Cuba and Pablo Neruda from Chile, as well as the likes of Jean-Paul Sartre and Hermann Hesse – hip authors of the early 70s. And I eventually discovered people such as Shelley and the radical English tradition. But it was black literature that began it for me.” His reading now ranges from Colin Channer’s Jamaican novels – featuring “love, sex and a bit of philosophy with titles from reggae songs” – to George Lamming’s essays, TS Eliot and Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose “strange diction really struck a nerve with me as soon as I heard it”. But now, as from the beginning of his career, what motivates him to write is politics. “Writing was a political act and poetry was a cultural weapon – though my early writing was a load of rubbish really. I tended to use lots of ‘thees’ and ‘thous’, which is what I thought poetry needed.” These early efforts soon progressed to unconscious imitations of Derek Walcott and then, more fruitfully, work influenced by Kamau Braithwaite. “Braithwhaite was so inspiring because he more or less subverted the whole canon of English poetry. There were elements of jazz, you could hear the drums, and the language of West Indian folk tales. This was about the Caribbean and the new world experience.”

Johnson was aware that he was living through an exciting political period. “We thought we could change the world. There was the anti-colonial struggle in Africa. The civil rights movement had been followed by Black Power. There was the anti-Vietnam war movement.” On a local level, being active in race and political issues in south London had its risks. His mother was concerned that he would come into conflict with the police. “Black people were being framed and brutalised, deported and imprisoned. People died in prisons. She felt as strongly as me about the racism we were facing, but she was more constrained in her response than us youngsters were.” Johnson was politically active while studying sociology at Goldsmiths, but by the early 70s, with the demise of the Black Panther movement, he felt there weren’t any political organisations that he “could make a useful contribution to in terms of the revolutionary position I had envisaged. So I went through a sort of cultural nationalist phase. Part of that was an attraction to Rastafari, which was very alluring in terms of the subversion of the English language, the dissident philosophy, the anti-colonialism and the spirituality.”

He tried to grow dreadlocks – “but I didn’t have the right hair” – and began to work with a group of Rasta drummers with whom he found a distinctive poetic voice. “The music was a very important part of it. I remember loving this three-album set called Grounation by Count Ossie & the Mystic Revelation of Rastafari, which seemed to have everything. There was narration, drumming, chanting, jazz, poetry, oratory, history. It just freaked me out.” His involvement with Rastafarianism eventually foundered on the fact that, as an atheist, “I couldn’t reconcile myself to the idea that Haile Selassie was God. And I didn’t think the wholesale repatriation to Africa was either practicable or desirable as a political project.” His politics progressed from Black Power to black working-class, and he joined Race Today. This collective published his early poems in its journal and then, in 1974, his first collection, Voices of the Living and the Dead. The following year, Bogle-L’Ouverture published Dread Beat an’ Blood, although he says it was “a bit of an uphill struggle to persuade them. They thought it was too violent and people advising them said it wasn’t good poetry. But in the end, they were persuaded and then things began to happen quite quickly. Dread Beat an’ Blood was basically written for the stage, for voice and drums, so it was a natural step to record it as an album.”

His work acquired increasing mainstream literary acclaim, but he didn’t feel part of any tradition. “I really thought I was doing something new. It’s not until later that you realise all trailblazers have trailblazers who preceded them. But there wasn’t anyone else writing about the black experience in Britain in the kind of language I was using and from the aesthetic I was coming from. These were poems to read at rallies and demonstrations and cultural gatherings of a political nature. So when I was published by Penguin, it was a big thing.” He is no longer on the Classics list – “when Milosz died, I became even more of an anomaly” – but is delighted to be reprinted on the mainstream Penguin poetry list. “I really don’t want to be the only guy alive on a list full of dead people. I’m just middle-aged, you know. I’ve got plenty of time left and things to say.” He says his increasing focus on black working-class politics has allowed his work to speak to national and international audiences, including parts of Europe where there are very few black people. “It’s not difficult to see parallels between the black working-class struggle going on in this country and things like Solidarity in Poland. Bob Marley wrote about Trenchtown, but people had no problem taking that to Birmingham or New York. I still begin with the particular, and hope to arrive at the universal.”

Looking back over 30 years, he sees life for many black people as having been “one step forward, two step backwards. And sometimes the other way round.” He points out that there are still too many deaths in police custody (“black and white”); that the recommendations of the Macpherson report – which charged the Met with institutional racism – are being whittled away; and that the old issue of stop and search is again on the political agenda. “And these things all still exercise me. Of course, it’s great to be at the Barbican playing with wonderful musicians. I really enjoy performing to an audience who now bring their grown-up children to my shows. It’s like life after death. But the thing I’ll always be most proud of is when an old woman comes up to me in Brixton market and asks: ‘Are you the poet?'”

Inspirations

The Bible Derek Walcott Kamau Brathwaite Gerard Manley Hopkins Count Ossie & the Mystic Revelation of Rastafari

https://furious.com/perfect/lkj.html

https://furious.com/perfect/lkj.html

Interview : Linton Kwesi Johnson

Few musical performers have done as much for both music and politics as Linton Kwesi Johnson. There are many causes and struggles that musicians take up to support now and then but LKJ’s whole career has been based on putting stories of struggle and oppression into his audience’s lives as well as leading organizations to battle racism in his native England. Starting out in the early ’70s, LKJ became a founder of the style of dub poetry- a mixture of Jamaican-styled speech mixed with the slippery, ghostly sounds of dub music. As a poet, he is easily the equal of Allen Ginsberg. As a sharp political theorist, he’s right up there with Noam Chomsky. As a musician/performer, he is a pioneer.

Special thanks to KEVIN SUSSMAN and PETER HITCHCOCK for helping add some good insights.

You were originally born in jamiaca and came to england at a young age. what do you consider your real home to be?

My parents came to England and I was told to come over at their request. At first, it was traumatic because of the hostility of racism and so on. But when you’re young, you tend to adjust to new situations pretty quicky. So I adjusted quickly and I’ve been settled here ever since. I do have a strong attachment to Jamaica. I have brothers and sisters there, aunties, cousins and others too numerous to mention. My mother retired and went to live back in Jamaica. I’m living here for 33 years now but I do intend to retire in Jamaica. I’m Jamaican-domiciled in fact.

Do you feel it’s more important to do your work in england for now then?

Yes, we’ve been doing important work over the years. It still needs to be done. There’s a new generation coming up but I’m not sure that they’re historically aware as my generation were. So there is that need to pass on to the next generation some institution building that my generation embarked upon. But I would like to contribute something to the land of my birth as well.

With your work with in the black panthers, greater london council and creation for liberation, did you your find that the work or mission differed for you?

The GLC was a job. In the Panthers, I was an activist. I was a Young Panther. That’s where I learned my politics and about my history and my culture. That’s where I discovered black literature, particularly the work of W.E.B. DuBois, the Afro-American scholar whose SOULS OF BLACK FOLK inspired me to write poetry. The work I did in Creation For Liberation, a lot of the things we initiated are now happening on a big scale. In a sense, our organization became redundant. For example, there were no art exhibitions done for black artists. Now there are open on a very big scale and there are quite a few black art galleries open up and down the place. Writers’ Forum, inviting black writers from America, the Caribbean and Africa. Having their work exposed to audiences here. Having them talk about their work and so on. That’s just some of things that people are doing right now.

I know that you’re not a rasta but how do you feel about the rastafarian movement?

Rastafari is a part of my historical heritage and a part of my cultural roots. Rasta has influenced Jamaican culture in a very big way. Not only in terms of the music but in terms of spirituality that it lent to reggae. Also in terms of the language, the Rastafari that has become a part of everyday Jamaican parlance, spoken by non-Rastafarians. My very first group was, in fact, called Rasta Love, which was a group of rasta drummers. We used to accompany my poetry with bass drum, funde drum and repeater drum. In all of my albums, there’s also some repeater playing percussion in the background. Rasta is important for me on that level- as a cultural force that broadened our consciousness and opened our consciousness to our African hertitage and our African ancestry.

With your poetry and lyrics, you use a creole, jamaican type of english to craft words. is this a more personal way to express yourself, by reshaping the language?

It’s interesting that you should ask that because only this year a book came out that I reviewed for the Guardian newspaper. It’s called A DICTIONARY OF CARIBBEAN ENGLISH by Richard Allsop. He tries to codify a lexicon of Caribbean speech, given the different island variations. For example, one fruit could be called one thing on one island and could be called an entirely different thing on another island. There has been, from the late sixities, a dictionary of Jamaican creole which was compiled by a man named Cassidy.

As far as the writing is concerned, a revolution was started in Caribbean poetry by Edward Brathwaite where he was trying to create a new aesthetic that wasn’t based on the meter of English poetry, the iambic pentameter. He incorporated the rhythms of Caribbean speech, jazz rhythms, blues rhythms, calypso rhythms and so on. In a sense, what I’ve been doing with reggae, what I call reggae poetry is to consolidate that revolution that was started by Brathwaite in terms of the language and in terms of the aesthetics.

In your early work, you talked about taking about violence towards blacks in england. but with more recent work, like ‘mi revolutionary fren,’ you sound like you’re shifting your focus to other, outside events.

‘Mi Revolutionary Fren’ was about the changes in Eastern Europe. I arrived at the position that Blacks don’t live in isolation in England and that our fate is tied with other events that are taking place in other parts of the world. That’s why I started to focus on other themes that the Black experience in Britian. I think that will probably be a feature of my work in the future.

With relation to your political views, what do you think is necessary to bring about change? do ends necessarily always justify means?

I don’t know if means always justify the ends. I don’t have any blueprint for solutions to problems. I think we made a tremendous amount of progress. We’re no longer the marginalized immagrant group that we were 25 years ago. We’ve made progress, we’ve made strides as a consequence of our struggles. I think the only way forward is for there to be a political will on the part of the establishment to tackle head on, for example, the issue of rascism within the police force. In the last 25 years, at least 50 black people have died in police custody, which is disgraceful record for any democratic country. There needs to be a political will to tackle the issue of rascist and fascist attacks against the Black and Asian communities by terrorists. That, I think, can only be the way forward.

How do you pick and chose which struggles and causes are worth bringing attention to or getting behind to support?

There’s no particular criteria I suppose. I get invovled in those struggles that I feel very strongly about and which I think that are organized properly. If it’s just some rebel-rousers trying to peddle their ideological tendancy, I’m not interested in that. If, for example, people from Marxist groups, from Maoist groups, from Social Democratic groups want to form a broad front to tackle to the issue of racism and rascist attacks then that’s the kind of thing that I would want to involve myself in.

Which these struggles that you’ve been invovled in, what’s been the common root of most of it starting? fear, ignorance?

I think a lot of it has to do with ignorance and a culture of racism that’s been ingrained since the time of the empire. It can even be found in the literature of the late nineteenth century and so on. It’s been ingrained in peoples’ mentality. And the institutionalized racism of the state and the state instituition.

What do you think is the best way to stop this then?

One thing we can do I suppose is whenever people perpetuate racist and fascist attacks and they’re apprehended, the due course of law should take place and these people should be convicted. That’s very, very difficult in this country for a white jury to convict a white person of committing racist attacks. There was a case a couple of years ago where a black guy was stabbed by some racists and they were apprehended. The police messed up the case and organized it so badly that the Crown Prosecution Service figured out that there wasn’t enough evidence to convict the people, even though they found the murder weapon and they had witnesses. The parents took out a private prosecution and of course, it didn’t get very far in the courts. So, I think we need the will to use the law as it exists against these people, in the same way to use the law against racist police officers who kill black people.

Do you think the race problems in england are similar in any way to those in the united states?

There are some similarities and some parallels but I think it’s always a mistake to draw broad comparisons between the black struggle here and the situation of blacks in America. To begin with and most importantly, blacks have only been here historically since the Second World War. There are blacks that have been here since ancient time but I’m talking about black community. It’s a post-World War II phenmenon. We’ve making our history over the last forty, fifty years whereas blacks in America have a history that goes back to the time of slavery. We don’t have segregation in this country, for example but you have it in the United States of America. There are lots of things that we can learn from the United States but I don’t think we should ape what is going on there.

In america, afro-centric teaching has become popular recently. what are your thoughts about this movement?

Frankly, I don’t know what Afro-centric means.

Black children are taught that civilization began in africa.

So, once you learn that, so what? That’s my attitude. Once you know that black people were a part of ancient cilivization in Africa and that African civilization has contributed a lot to world, what next? That’s my position. Where do we go from there?

Part of the reasoning behind this is to instill a sense of pride in the community. the children are taught that their ancestors were kings and queens and not just slaves that were brought over here.

Yes, that’s alright. But once you’ve done that, where do you go from there? You can’t tell the children that all of us were kings and queens because if there were kings and queens then they must have ruled over somebody else.

What type of political system is closest to your view about how a country should be organized?

Socialist democracy. Socialist in the sense that the state is in a position to protect those who can’t protect themselves and to ensure to ensure that the basic human rights of food, clothes and shelter are taken care of. There is no one-party state but a plural democracy where governments can be elected and de-selected.

Are you worried thought that socialism has led to fascism and communism in many countries?

I don’t think socialism has ever led to communism or fascism. I think that it’s the dialectic opposite of fascism. The word ‘socialism’ is probably one of the misused terms in the history of words. When a lot of people talk about socialism, they don’t really mean people power. As far as I’m concerned, socialism means more power to the people, more democracy, more freedom. What they had in the Soviet Union was a one-party state. Once you have the one-party state, that’s the end of democracy. It creates all the conditions for corruption, nepotism. It has nothing to do with socialism.

How effective have you found your records and your performances in helping with enlightening your audience and others?

Well, it’s very difficult to measure these things. One can speculate that people invite you to various countries to perform and people always turn up to hear you. That means that they’re listening. I do know that a lot of people in Europe are informed a lot about the black experience in this country by listening to my records.

What do you find to be different about doing a lecture versus doing a performance?

I don’t really do lectures, I do poetry readings. The difference between that and performing with a band in front of an audience is that the audience that comes to hear the band are usually there for that element. When people come to hear the poetry reading, they come for the poetry and it’s much more intimate. Sometimes, it’s more rewarding than performing with a band. Sometimes you perform with a band in front of thousands of people and it’s very impersonal whereas with a small theater with a few hundred people, you’re looking into peoples’ faces and they’re looking into yours. You’re feeding off their vibes and they’re feeding off yours. I like both but I think that performing with a band is much easier because the attention is focused on the bass player, the drummer, the keyboard player. Whereas when I’m reciting poetry, it’s just me and me alone.

You decided to retire from doing performances in the mid-eighties. what led you to make that decision?

There were a few things. One, I was a little bit tired of being on the road. Two, there were certain people in the organizations that I was invovled in at the time that felt that I was needed at the base to carry out organizational activities. Three, I wanted to take a little bit of time out to do a little bit of writing as well.

Do you have plans for new releases and tours?

Yes I do. I’m planning to start working on a new CD sometime next year. I don’t think I’ll be doing as much shows. I’m doing quite a bit over the last five years. Touring all over Europe, Japan, Brazil, South Africa and all these places. So now I want to take some time out and do some production for my label (LKJ Records) and to do some creative work, some writing and some recording.

With the new cd, do you have some idea of what it’s going to be like?

I never do. I’m just writing at the moment and once I have enough material that I think is good enough, then I’ll go to the studio.

With the material you’re writing now, what kind of things are you thinking about?

There’s a lot of things. I’m preoccupied by death, love, struggle, politics.

You made a quote once that you thought that bob marley had watered down his music and his message once he signed to a big label.

I know. I’m afraid I’ll have to live with that statement. That was when I was in my more furious frame of mind. But I regret having said that because it’s not really true. I believe that the music was internationalized to reach a greater audience but I don’t think it effected his message in any way.

http://socialistreview.org.uk/263/mekin-sense-outta-nansense

Linton Kwesi Johnson:

Mekin Sense Outta Nansense

By Yuri Prasad

What was it like to be a poet and a black political activist in the 1970s? How did the two come together and what kind of issues did you take up?

I came to poetry via politics. I discovered black literature as a consequence of my involvement in the Black Panther movement. We never came across any black literature or literature about blacks at school. When we did history–we did British history, we never did anything about slavery.

Part of my awakening was a book called ‘The Souls of Black Folk’ by WEB Dubois. It moved me very deeply, stirred something within me, and that made me want to write. That book was about the experiences of African-Americans in the post-emancipation period. So for me writing poetry was a political act. It was a way of articulating the anger and the hurt of my generation–growing up as black youth in a racially hostile environment.

I didn’t believe that at that time a black poet could have the luxury of art for art’s sake. It had to be in the service of the struggle. I tried to use poetry to highlight particular movements and to record certain events. I was involved in the campaign for George Lindo, a guy from Bradford who was framed by the police on a robbery charge–I was inspired to write some verse about it. I was involved in the carnival movement, and when they tried to ban the Notting Hill Carnival in the 1970s I wrote a poem called ‘Forces of Victri’. There was the campaign to get rid of the infamous sus laws, the old Vagrancy Act that was suddenly rediscovered and used against my generation, mercilessly by racist cops. I wrote a poem dealing with that called ‘Sonny’s Letter’, which took the form of a letter from prison. That’s the way that my poetry and my political activity came together.

Do you think that the battles against racism that you fought in the 1970s have to be fought again today, and do you think that racism is getting worse?

Certainly in places like Oldham and Burnley it sounds as if it is getting worse. I think that is largely due to the fact that a section of the working class has been neglected, particularly in the areas where the Labour Party is known to be corrupt.

I don’t know if racism in general is getting worse. I remember a time when trade unions came out in support of Enoch Powell and his demand for repatriation. They marched in London shouting, ‘Send them back,’ and all that. Today you have a black man, Bill Morris, head of the Transport and General Workers Union, one of the biggest unions in the country. That’s a measure of how far things have changed, and I think we have made progress.

The Macpherson report finally admitted that most of Britain’s institutions, including the police, are racist. I remember when the New Cross fire happened, within 24 hours, without any investigation and without any forensic evidence the spokesperson for Scotland Yard ruled out the possibility that it could have been a racist attack. We’ve come some way, but we still have to fight for equality and social justice.

The question of police racism is still here. The fact that throughout the 1990s we have the frightening rise in the incidence of black deaths in police custody is indicative of that. The five police officers who have been indicted in Hull in connection with the death of Christopher Alder are an example of that. So is the case of Roger Sylvester. In some ways we have made some progress, and in others we haven’t made any progress at all.

Increasingly music is adopting a hybrid form–it is borrowing from many cultures. Do you see any connection between that and the development of a global movement against capitalism?

It is a reflection of the world in which we are living–reggae itself was a hybrid music. People talk about the global village–everywhere you go people are fighting back against all kinds of oppression. Whether it has taken on a global dimension I don’t know. What I do know is that I am 100 percent in support of the anti-capitalist and anti-globalisation movement. Somebody has to stand up to these multinational corporations.

The power of international finance capital is making national sovereignty increasingly meaningless–even if we make certain demands on our government, they are limited as to what they can and cannot do. I recently saw a film about Jamaica called Life and Debt, which showed how the IMF policies had impacted on Jamaica. When I saw that film what came into my mind was the anti-capitalist movement.

The film explained in an eloquent way why these movements came into being. It’s good that film-makers, singers, songwriters and dramatists are dealing with these issues. How people respond is up to the individual artist. You can’t legislate for art. It comes from the soul–you can’t tell people what to focus upon.

I am very disappointed by this New Labour government. I don’t think that they have moved radically to match their rhetoric. It still feels like the Tory period–business as usual. The sense of hopelessness and the sense of despair are still here, particularly in industrial England. What is New Labour doing about it?

How do you feel about your engagement with the movement for social justice now?

I’m a little bit more dislocated than I used to be, because my main involvement was in the radical black movement, and that has gone into decline in the years since Thatcher. I try to support local struggles. There was a time when I was out supporting the miners, but all those types of struggle are not happening.

But I am still deeply committed to the idea of social justice, and to bringing about racial equality and radical change. My audiences are getting younger and younger. There is a radical current out there among the young people. They are looking for something to get involved in, to channel their rebellion into, but ‘tings and times’ have changed, and 2002 is not like the 1980s.

https://newhumanist.org.uk/583/leggo-relijan-laurie-taylor-interviews-linton-kwesi-johnson

Laurie Taylor interviews Linton Kwesi Johnson

Laurie Taylor

Q You told me on the phone before I came over to Brixton to see you that you were pretty fed up with interviews…

A I get sick of the same questions. I get sick of being asked impossible questions about what is the meaning of life and what is happiness. I get sick of being asked questions by people who haven’t bothered to do their research. They ask when I was born and where I was born and what school I went to, when all they have to do is to look it up. I’m suffering from interviewitis.

Q But you must have been impressed by how many people listened to one of your last interviews – the one with Sue Lawley on Desert Island Discs. I remember talking to you at a Christmas party and all the time people were coming up and saying how much they’d enjoyed the programme

A Yes, that’s true. I didn’t realise how many people listened to it. I’m walking along Railton Road and this middle-aged West Indian guy stops me in the street and says “Congratulations”. I said “Congratulations? What for?” And he said “Your programme on the radio, man. It was really good.”

Q Unless I’ve missed something, you’ve never talked about the part that religion played in your life when you were growing up in Jamaica.

A Religion? I grew up taking it for granted there was a God. It was something you never questioned, you know. I did question it one time when I was about seven or eight. My grandmother who was looking after me and my little sister had to go off somewhere and left us in the care of one of the church sisters. And I don’t know how the conversation came up but I said to her, “Well, if God made everybody, who made God?” And she said “You wicked little boy! Wait till your grandmother get back. I’m going to tell her what you said.”

We were native Baptist. We were poor black people. I come from the heart of Jamaica. We had a peasant existence. Farming. And the church is the hub of all the social life in such a place. You’d look forward to the harvest festivals. And the only bit of theatre you had was in the church where they’d put on little performances and recite poetry and do skits. You’d go to church twice on a Sunday. Sunday school in the morning and a proper church service in the afternoon. That was always dead boring. Us boys would get up to mischief. If an older person fell asleep, we’d roll up paper and put it in their mouth. One or two of the older boys would go so far as to light it.

Q And your education was closely bound up with religion?

A Oh yes. My schoolteacher was the organist in the church. Miss Miller. Funny it is, you know. She used to play this little warm-up bit before the church service proper began and I remember as a little boy often getting an erection listening to her playing the organ.

There was definitely something that I found erotic about the church organ. Most of our other music was religious. We sang hymns at school. From Sankey. And my grandmother would sing sacred songs at home. She would often sing such songs when her mind was troubled. When she started singing hymns you knew that something was up. But Baptists were pretty sedate. It was regarded as more sophisticated than the clapping churches. I don’t remember any beating of tambourines.

Q And did your religion take more of a back seat after you arrived in this country at the age of 11?

A Not at all. When I came to this country, my mother sent me straight to Sunday school and to church. I was involved in the Methodist church up Brixton Hill. I sang in the choir for a little while. I took part in the youth club and even when I got to the age when my mother couldn’t insist any more – when I was a teenager – I just went along voluntarily. I suppose it was habit.

I used to go to the Sunday service at eleven in the morning and then be back for Sunday dinner and then I was in Brixton at the Ram Jam Club by three o’clock. My mother used to say, “You’re worshipping God and the Devil on the same day!”

I first began to question religion after reading Capitalism and Slavery by Eric Williams – Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago from 1961 until his death in 1981. I discovered the role that religion played in the enslavement of my people.

I was absolutely astonished to discover that during the fifteenth century when there was rivalry between Spain and Portugal – two leading Catholic countries – about the so-called New World, the Pope said to the Spaniards, “Okay, you can have America.” And he said to the Portuguese, “Okay, you can have Africa.” And I thought. “Fucking hell! How can this man just give me away to the Portuguese? Who is he? How dare him do dat!”

And then the questions began to go deeper. I did CSE Religious Education and got a Grade A and did a project on the Methodist Church. That was when I discovered that Charles Wesley was a high Tory who was pro-slavery. And I thought, “Are these people representing God and the interests of slavery at the same time? There’s something deeply wrong here.” By the time I got to university I was reading Marx and learning about how religion was the opium of the people.

Q You saw the role that religion had played in making the colonised passive?

A It was never as simple as that. I remember later discovering liberation theology and realising that these Latin American priests were involved in the struggles that were taking place down there. And I knew that some preachers – particularly some Baptist preachers – had been opposed to slavery. People like Paul Bogle, the Baptist deacon who led the Morant Bay rebellion in 1865 and Sam Sharpe who has Sam Sharpe Square in Montego Bay named after him. He was captured and hung after leading the biggest slave rebellion in Jamaica’s history.

My transition from the taken-for-granted God as the creator of the universe to a more agnostic position came through Rastafari. I must say it was quite an attractive religion in terms of its ideas. It was against the domination of whites over blacks. It was against colonialism. It was for Africa. It was for rejecting a lot of the materialist values associated with capitalist civilisation. And it had a spiritual dimension that saw God and godliness as some kind of spiritual force with which all human beings were imbued.

But although I identified with these values I couldn’t identify with the idea – this might sound arrogant – but I couldn’t identify with the idea that Haille Selassie was God. He was just a human being like everybody else. And if he was God why did his people have to suffer so much from hunger and drought? And I couldn’t identify with the back to Africa thing. I knew that the history of human civilisation is the history of the movements of people from one part of the globe to another. Once couldn’t turn the clock of history back.

Q You were never sympathetic to the Black Muslims?

A I was always against them. Because for me it was an inversion of fascism. It was replacing one racist ideology with another. I was politically blooded in the Black Panthers back in 1970 when I was 18. I was even arrested in 1972 for taking policemen’s numbers after they mishandled some kids in Brixton Market.

The Panthers – particularly in America – were always at loggerheads with the Muslims. It was ridiculous. The basis of the Black Muslim philosophy and worldview was a load of nonsense about some scientist creating white people out of rats and pigs. An insult to my intelligence. And, of course, they killed ‘Malcolm X’. That was a no-no.

Q You seem to have considered a number of religious standpoints. What finally made you stop searching?

A I observed that a lot of people I knew who were atheists were in their social life, in their human relations, far more humane and compassionate and decent than a lot of the religious people I knew. A lot of the Christian people I came across were fucking hypocrites.

Q So where does your own morality come from – your own values?

A I inherited my moral values from my parents and my grandparents. They were influenced by Christianity, of course, but there were a lot of values they held that I regard as humanist values. Enduring human values. Compassion, a caring attitude towards other people, and a capacity to forgive. Once those values disappear it’s the end of humanity.

Q I suppose you have been in the conversion business for much of your life. Trying to change people’s consciousness with your verse and your music.

A I’ve never been under the illusion that art changes anything. But I know that what I’m doing is still worthwhile if only insofar as I’m acting as a history teacher. A lot of the struggles that the black community waged in this country in the 70s and 80s have not taken place in certain parts of Europe where the so-called immigrant population are only now reaching where we were back then.

Hence the relevance of my verse and my music. Struggles are taking place in Holland and Germany and France. People don’t realise that the black communities in this country are more politically advanced than our European counterparts.

We’ve built more institutions and we’ve brought about more change. And therefore the body of experience that informs my work is relevant. Like my poem about deaths in police custody – ‘Licensed to Kill’. When I go abroad everybody can identify with it. No, I’m not irrelevant yet.

Q But are there new things to be said? New issues for your poetry?

A There’s always new things to be said. It’s whether or not I’m inspired to say them. You do tend to get a bit more inward looking the older you get. As you meditate on your own mortality. As your hair recedes and goes grey and you worry about losing your sexual powers.

Q Do you feel a sense of affinity with other poets? Do you feel part of a poetic tradition?

A When I was younger, with the arrogance of youth, I saw myself as a radical revolutionary poet who was breaking with the old tradition. But as I’ve gotten older I realised others have blazed trails before and I’m grateful for them.

Grateful to people like the Barbadian poet Kamau Brathwaite for having cleared the debris. If they hadn’t experimented with the language there’d have been no Linton Kwesi Johnson. My poetry comes from a different aesthetic than the dominant English one. I’m a product of a hybrid culture, so my aesthetic could never be solely based on the canon of English culture.

Q But does that mean your poetry is primarily poetry about the black struggle? That often seems to be the sub-text when you are described as a ‘black poet’.

A ‘Black’ in ‘black poet’ is a political prefix. When I began to write poetry in the early days it had to be about politics, struggle and change. Nowadays, I’m fifty and middle-aged and I start to look back at the stuff I read then written by black poets which was not about the struggle.

Absolutely beautiful poetry which touched the human soul. I particularly remember a poem which was very derivative of English poetry called ‘Fugue’ by Neville Dawes, a Jamaican novelist and poet. The language was reminiscent of Dylan Thomas. Fantastic.

But when I began to write verse that wasn’t what inspired me. I was more interested in the political poetry of someone like the Guyanan Martin Carter.

Q Do you write every day?

A I’m too busy earning a living to write now. I’ve recently returned from a long tour : Japan, USA, Germany, and France. The muse visits me from time to time but she doesn’t come as often as she used to. I’ve unfortunately not given her enough attention. She’s a very jealous person. She needs a lot of attention. And because I don’t give her enough she doesn’t come to see me any more.

Q You talk a great deal of being older, of being past your best. But you’re only fifty. You’re still young.

A Young! I suppose I’ve always had that. I never thought I’d live to see thirty years old. In the revolutionary politics in which we were involved so many people were dying in prison, so many people assassinated. And we were prepared to sacrifice our lives to bring about change.

I never thought I’d live to see thirty, so now I’m fifty I think I’m very old.

Linton Kwesi Johnson: ‘It was a myth that immigrants didn’t want to fit into British society. We weren’t allowed’

By Decca Aitkenhead

When Linton Kwesi Johnson was a boy, he wanted to grow up to be an accountant. “If I was an accountant,” he chuckles softly, sitting surrounded by piles of books and CDs in his modest south-London terrace house: “I would probably be a multimillionaire by now.” The world, on the other hand, would be considerably poorer.

It is 40 years since the Jamaican-born poet made his debut as a recording artist. The release of Dread Beat an’ Blood – an album of radical political poetry spoken in Jamaican patois, set to a reggae beat – created a new literary genre known as dub poetry, and introduced Johnson, now 65, as the voice of the Windrush generation. Neither he nor his work was universally welcomed. The Spectator memorably accused him of helping “to create a generation of rioters and illiterates” (the magazine was appalled by his phonetic spelling – as in “massakaha” for massacre, say) and he remembers how the police arrested and beat him up. Yet he became only the second living poet to have his work published by Penguin Modern Classics, and was the 2012 winner of the Golden PEN award for his “distinguished service to literature”. Next month, his contribution to the country’s cultural life will be honoured at the Southbank Centre in London – an occasion whose significance has been intensified by events of recent weeks.

Johnson describes himself as a reluctant interviewee. “I’ve got interview fatigue,” he smiles before we have even sat down, and it is true that he can be quite diffident and reserved. But rereading all the interviews he has given over the years, I was struck by how comprehensively they chart each turn in the evolving history of British race relations. From the Black Panther movement to the New Cross fire and Brixton riots of 1981, through the Metropolitan police’s notorious Special Patrol Group, the Stephen Lawrence murder and the Macpherson report, right up to the Grenfell Tower tragedy, Johnson has provided the social commentary absent from so much of the public narrative. Sometimes, he has sounded full of rage – and at other times, more hopeful. I’m curious, therefore, to hear how he would characterise the present moment.

“In terms of our country, it would be foolish to say that we haven’t made some progress. Because we have.” He cites the contrast between the “almost complete and utter indifference to the New Cross fire from mainstream media” with the “huge outpouring of sympathy for people affected by the Grenfell tragedy” and reflects: “I think it’s a measure of how much progress we’ve made; how integrated we are.” Then he pauses.

Johnson created the dub poetry literary genre … pictured on stage in Amsterdam in 1980. Photograph: Rob Verhorst/Redferns

“But, right now, we are living through a time of reaction; the rise of Conservative populism. And some things simply won’t go away. I’m sure I’ll be crucified for saying this, but I believe that racism is very much part of the cultural DNA of this country, and most probably has been so from imperial times. And, in spite of the progress that we have made, it’s there. It is something we have to contend with in our everyday lives.”

Linton was born in rural Jamaica in 1952, and arrived in London 11 years later to join his mother. “I remember when I was a youngster, there was always this myth that we were finding it difficult to integrate ourselves into British society. Or that there was a reluctance on our part to fit in with British society.” Most of the time. he speaks slowly, as if carefully measuring each word before committing it to speech, but occasionally they come firing out, and do now as he goes on: “And that was really a nonsense, because we are British! We were created by the British, for God’s sake.” The more deliberate rhythm resuming, he adds quietly: “The fact of the matter is we wanted desperately to integrate. But they wouldn’t allow us.”

Johnson has held a British passport since Margaret Thatcher was in power, but has known many Jamaican people who lived in the UK for years, only to visit the Caribbean and discover they were not allowed back. “So this Windrush scandal has been going on for a long time. But it is also symptomatic of the ascendancy of the Ukip wing of the Conservative party. Ukip doesn’t really exist in any concrete sense any more, but it is alive and well within the Conservative party. It has not only been the nasty party; it has been the anti-immigrant party.”

He takes heart from the public outcry that has forced the government to radically revise its hostile environment policy. “I think the vast majority of British people are outraged and think it’s grossly unjust. I mean, if you have got someone like Joseph [sic] Rees-Mogg, or whatever his name is, coming out and saying this is unacceptable, that’s a measure of the general public outrage.” I ask what the government’s abject apologies mean to him. “Well, there’s no harm in saying sorry,” he smiles, with a mischievous glint. “But people want their situation resolved.” Does he assume from everything the government has promised that it will be?

“Well, I hope so. Because if it isn’t, they’ve got a fight on their hands, I can tell you that.”

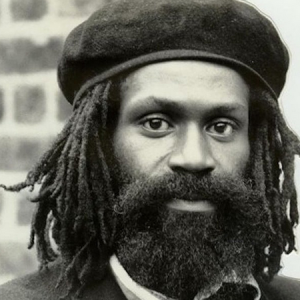

Johnson joined the Black Panthers as a schoolboy …pictured performing at the Lyceum, London, in 1984. Photograph: David Corio/Redferns

Johnson’s worry, he adds, is: “It’s not just the so-called Windrush generation, but other people, maybe from the Indian subcontinent and other parts of the Commonwealth, who will be affected by this.” The Brexiters in government, I say, blame EU membership for causing Britain to neglect its Commonwealth cousins, and promise that Brexit will put this right.

“It’s laughable,” he sighs. “Really, it is laughable.” He doesn’t know anyone in London’s West Indian community who fell for it. “I’m sure that some of our governments in the Caribbean may be hoping for some benefit. But that is very naive … very naive. I think when people in government are talking about the Commonwealth, they’re really talking about Australia and New Zealand and Canada. Not these little specks in the Caribbean sea.”

Johnson subscribes to Marcus Garvey’s belief that progress comes through autonomy, so has never looked to Westminster for progress. As a schoolboy, he joined the Black Panther movement, so I ask what he would join if he were in his teens today. “Oh, I would be in solidarity with Black Lives Matter, for sure.” Mainstream parties don’t interest him, he offers mildly. “Racist immigration legislation has been shared by both political parties. Winston Churchill talked about the ‘wogs’ and all that. So Mrs May, she’s not exceptional; there’s a historical continuity. And the Labour party is not exactly squeaky-clean. Though I’m very encouraged that in Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party, there’s now a different tone.”

Different enough for him to vote at the next general election? It has been Johnson’s lifelong policy to vote only in local elections, but after a brief pause, he nods. “I would probably give it serious thought.”

Although “a news junkie”, addicted to TV news channels, he admits: “I’m just bloody useless when it comes to computers.” Sending and receiving emails are as far as his engagement with the digital world goes, so online political activism passes him by. But I wonder if he shares the view of Cressida Dick, David Lammy and others that social media is playing a part in the current eruption of youth street violence.

“Yes, I would agree it plays a part. All these youngsters with their smartphones, ratcheting it up.” He cites austerity as another factor, but goes on: “I always try to remind people, gangs are not a new phenomenon. When I was a youngster there was gangs.”

Johnson says he carried a knife when he was young for self-defence, but stopped shortly afterwards when he injured another young man who was bullying him. Photograph: Rex Features

Why didn’t he join one? “I didn’t have the need to join a gang. I wasn’t a rudeboy – although a lot of my friends were. And I never had the herd mentality. I was always a loner. Nobody could get me to do anything I didn’t want to do.” He did, however, carry a knife. “I used to have a knife when I was about 15. It was about self-defence and it was a lot to do with fear. There were bullies around.” Would he have used it?

“I did. Yes. A guy was bullying me. He was bigger than me. I couldn’t fight him, so I took my knife out and went to slash him in his face. He put up his hand and I almost severed his thumb. I remember the youth club leader took him to hospital and had his thumb stitched up. And that was the last time I carried a knife.”

I ask why. “I thought: ‘I’m not going to do this.’ Because when you have a knife you forget you have fists. You forget that you have hands and feet, and the first thing you do is go for your knife. So, I understand a little about why people carry knives. It is to do with fear. And that has been around from time immemorial, you know.”

What has changed, he thinks – and for the worse – are relations between the police and black youths. He says his grandson – “who does not carry a knife” – gets stopped and searched much more often than even he was in his youth. The Macpherson report’s conclusion that the police were institutionally racist was, he says, a watershed moment – and attitudes of many senior officers have changed. “But the rank and file culture hasn’t changed at all.” They are still institutionally racist? “Of course they are. Of course they are.”

I am curious to hear what he makes of the proposal for a Stephen Lawrence Day. “Yes, why not? Why not a Stephen Lawrence Day?” he muses. Then he smiles. “You’re asking me these questions, as though as I have the answer to the problems of them. I don’t, you know.”

He becomes more forthcoming when recalling the early days of his career. After graduating in sociology from Goldsmiths in 1973: “I began to write verse, not only because I liked it, but because it was a way of expressing the anger, the passion of the youth of my generation in terms of our struggle against racial oppression. Poetry was a cultural weapon in the black liberation struggle, so that’s how it began.” He mentioned to a friend who worked for Virgin that when he recited his poems: “People say it sounds like music.” The friend suggested he make a demo tape. “And he arranged for me to meet Richard Branson. We met in this little Chinese restaurant in High Street Kensington, and Branson said he liked the tape.” What did Johnson think of Branson? “I didn’t think a lot. He looked like a hippy to me.” Branson signed him – and so Johnson became a reggae artist, he smiles, “by accident”.

A father of three, and now a grandfather, in 2011 Johnson had surgery for prostate cancer, and says it changed his outlook. “It’s made me perhaps appreciate a bit more how good it is to be alive. In Jamaica language, I would say ‘live up and love up’. You know, cherish humanity and cherish your friends and your children and your family.”

He no longer goes to concerts because he suffers from tinnitus. “My guilty pleasures are tobacco and alcohol. I like a nice glass of Guinness and a roll-up or a glass of wine and a roll-up. And I watch too much TV. Yes, I watch Strictly, X Factor, The Voice, those kinds of programmes.”

Johnson hasn’t written a new poem in more than a decade. “I hope I will write something in the future, but it doesn’t bother me if I don’t.” He doesn’t try to force it? “No.” I had thought he might have stopped writing because the anger that once fuelled him has faded.

“No, it’s because it has occurred to me that maybe I’ve written the best of what I can write already. I’ve known so many poets who have peaked at a certain period in their career, and then they’ve written inferior stuff in the years after. I don’t