Sonic spaces, spiritual bodies: The affective experience of the roots reggae soundsystem

Orlando WOODS, orlandowoods@smu.edu.sg

School of Social Sciences, Singapore Management University, Singapore,

Follow this and additional works at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research

Abstract

This paper advances a new understanding of spirituality within the geographies of religion. It builds on the premise that spirituality is latent within every body, and argues that it becomes manifest in response to an affective experience. Such experiences are often sensory in nature, rendering spiritual affect an embodied phenomenon that can be understood through the concept of an “embodied hierophany”. By exploring the affective experience of the roots reggae soundsystem, this paper shows how sonic spaces can enable processes of spiritual engagement. It draws on an analysis of four documentary films about soundsystem culture to show how situations of sonic dominance can bring about an embodied hierophany. In such situations, spirituality is experienced outside of the ascriptive framework of formal religious belief, and is therefore a more self-directed form of spiritual awakening.

Keywords: spirituality, sonic spaces, embodiment, affect, reggae, Rastafari

Every object have a shadow; you have to find your shadow. (Mad Professor)

1 | INTRODUCTION

Spiritual experience often occurs outside of the scriptural authority of religion; it is something that is felt more than it is thought. Feeling is an embodied phenomenon that may be understood through processes of (post‐) rationalisation and ascription to religious belief, yet the experience itself remains visceral. Various sensory triggers can stimulate a spiritual experience, one of the most affective of which is sound. Whilst sound is used in various ways by religious groups for the purposes of worship, ritual, instruction and reflection, so too does sound have more spontaneous and unprescribed affective qualities that exist outside of formal religious frameworks. Sound serves to “connec[t] people; it draws us together” (Henriques, 2003, p. 451) and it is increasingly apparent that “what we know about ourselves and others and the spaces we create for ourselves is also built out of sounds” (Stokes, 1997, p. 63). Beyond opening us up to social connection and understanding, so too can the affective experience of sound bring about a form of spiritual connection and understanding as well. Such experiences often occur outside of the formal praxis of religion, which helps to explain why they have not yet been a focus of scholarship (Dewsbury & Cloke, 2009; Yorgason & della Dora, 2009; see also Dwyer, 2016). That said, given that new forms of spirituality have started to encroach upon (and subvert) the domain of “religion” (see Heelas et al., 2005; Bartolini et al., 2016), work needs to be done to identify and understand the spectrum of forms found in different contexts around the word. This paper fills the lacuna by exploring the relationship between the body, spiritual engagement and sound within the ostensibly non‐religious context of the roots reggae soundsystem.

My argument is that spirituality is latent within every body and becomes manifest when triggered by particular sensory experiences. Whilst religion is a form of categorisation that is liable to (de)construction and debate (Knott, 2008), spiritual- ity is an expanded understanding of the self and its role in the world; it is an ineffable form of experience that is often and easily conflated with religion. Beyond conflation, religion tends to colonise spirituality, yet spirituality is much more nebulous and fleeting than the religious experience to which it may be ascribed. Spirituality speaks from within, rendering it a highly personal and subjective phenomenon (see Wigley, 2017). It is engaged through feeling, not constructed throughthought. Spirituality is the essential nature of the self, stripped of any sense of identity or belonging. That said, manifestations of spirituality are mediated by our encultured identities (and the biases and prejudices that are often associated with identification) and the tastes, preferences and sensitivities that can limit or enhance sensory experience (Woods, 2017).

Moreover, to the extent that spirituality is a felt phenomenon, it is also experienced (or not) by different people in different ways. Thus, just as religious affiliation can cleave people into groups, so too can spiritual experience create divisions according to the ways in which it is perceived, accessed and attained. Notwithstanding the variable experience of spirituality, the fact that feeling is an embodied phenomenon means that the sensory triggering of feeling renders the spiritual body an affected body. Through feeling, the spiritual self becomes manifest as the body is decoupled from rational thought and action and becomes a mediator between the spiritual and the cognitive self. A sense of the spiritual can thus be interpreted as an embodied hierophany, with the body being the axis mundi that enables the discovery and realisation of the spiritual self. Whilst the essentialist underpinnings of Eliade’s (1959) origi-nal conceptualisation of hierophany – the manifestation of the sacred in place – has since given way to more nuanced understandings of the (re)production of sacred space (see, for example, Holloway, 2003; Kong, 2001; Woods, 2013), this reflects the application of hierophany to religious landscapes rather than the embodiment of spirituality. Thus, if we take the idea that the body is inherently spiritual as a point of departure, then the concept of hierophany is both relevant and instructive, as it shows how spirituality can “erupt” in response to sensory artshum.

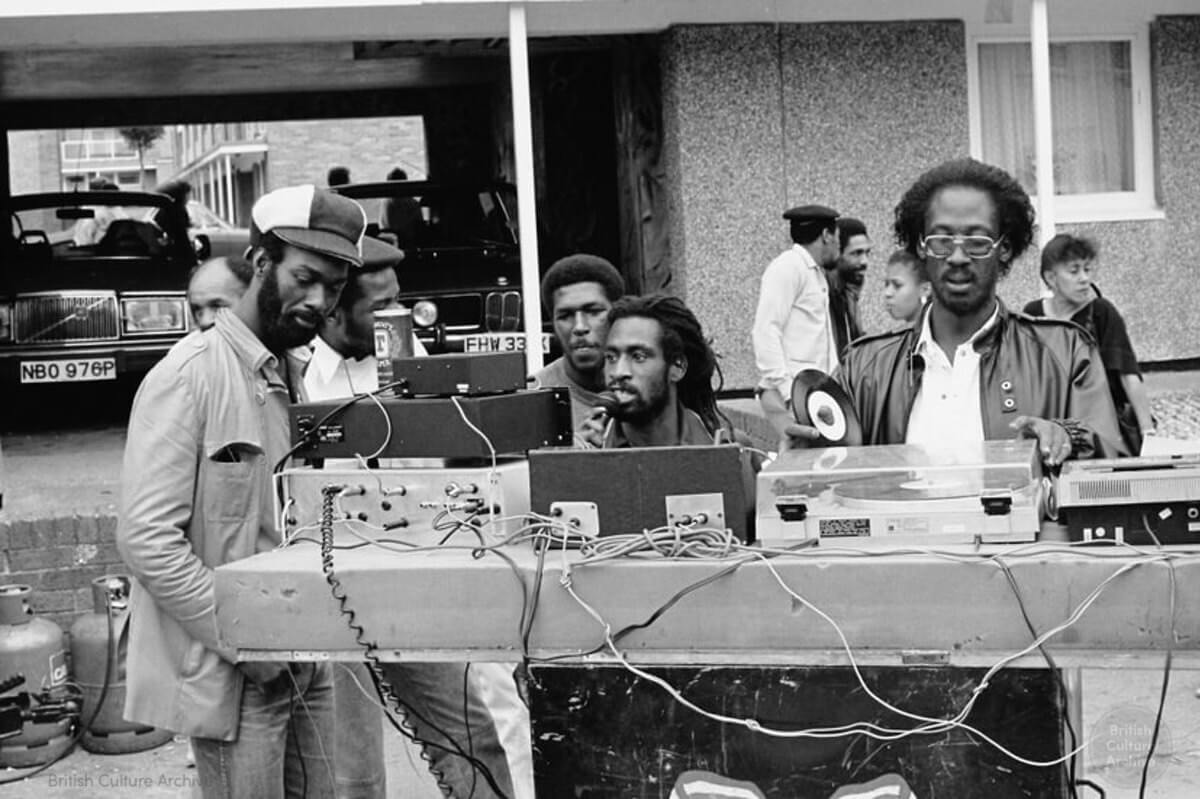

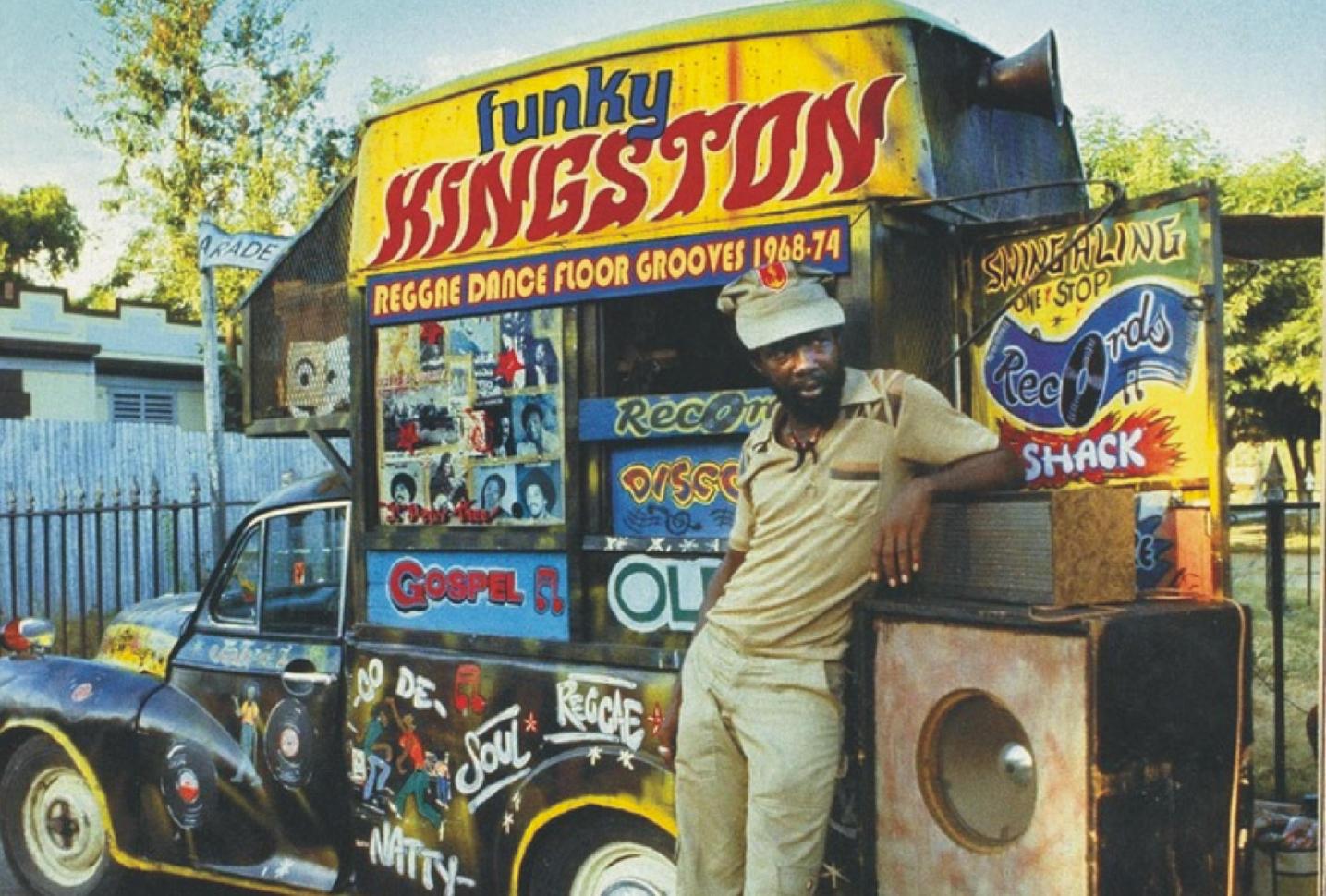

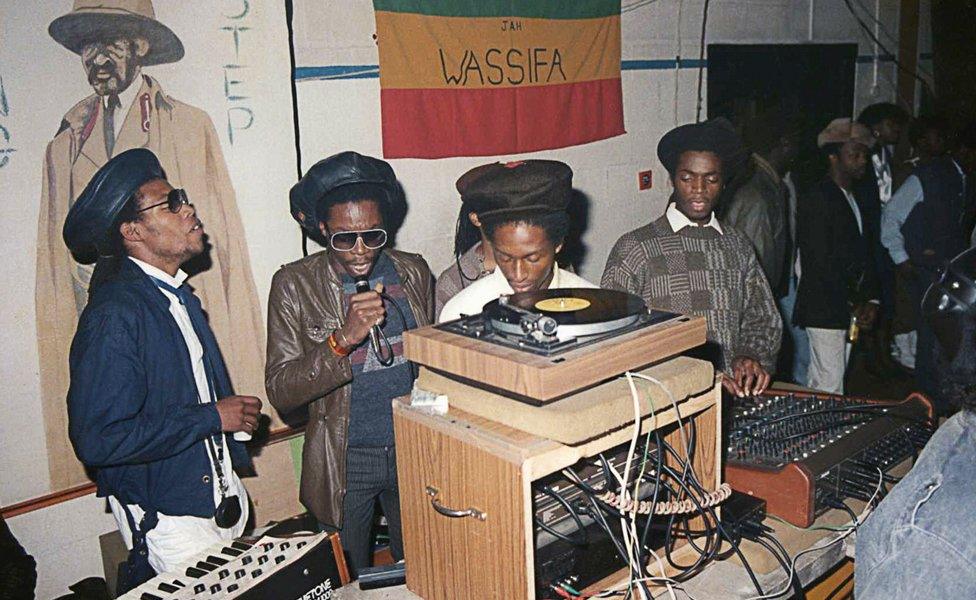

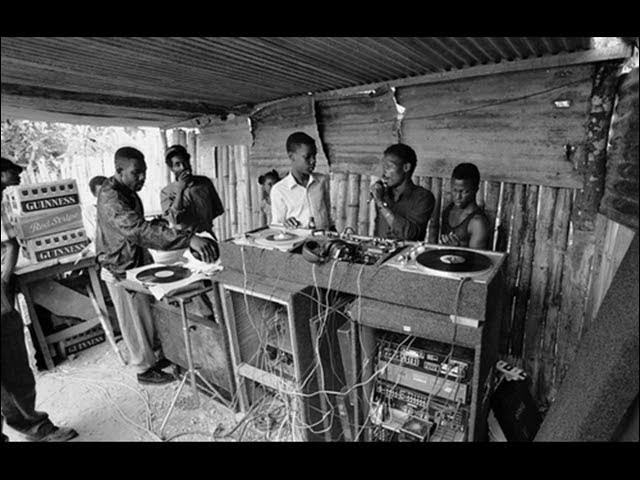

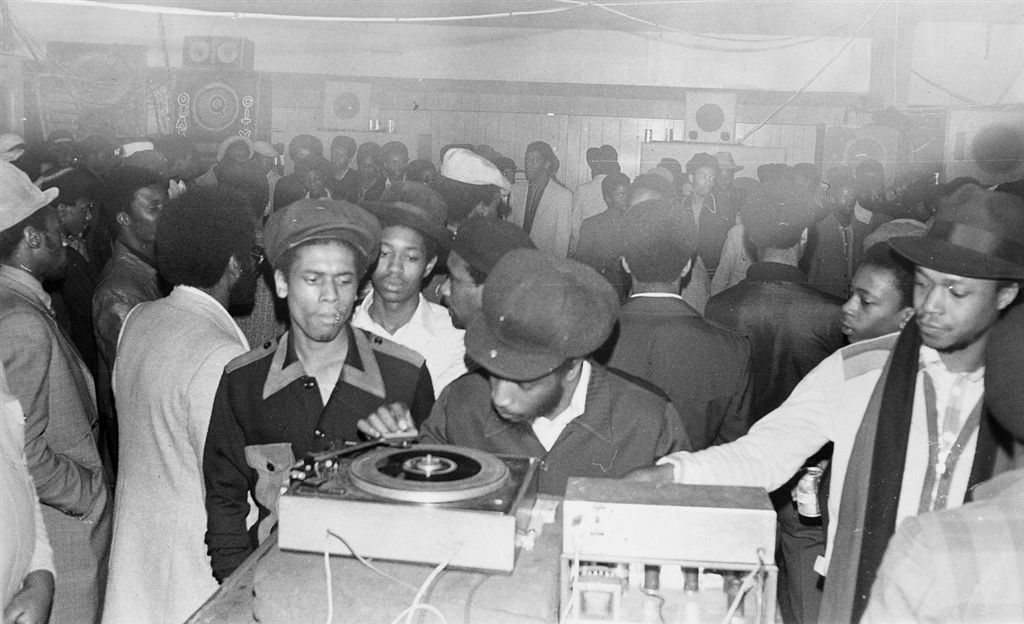

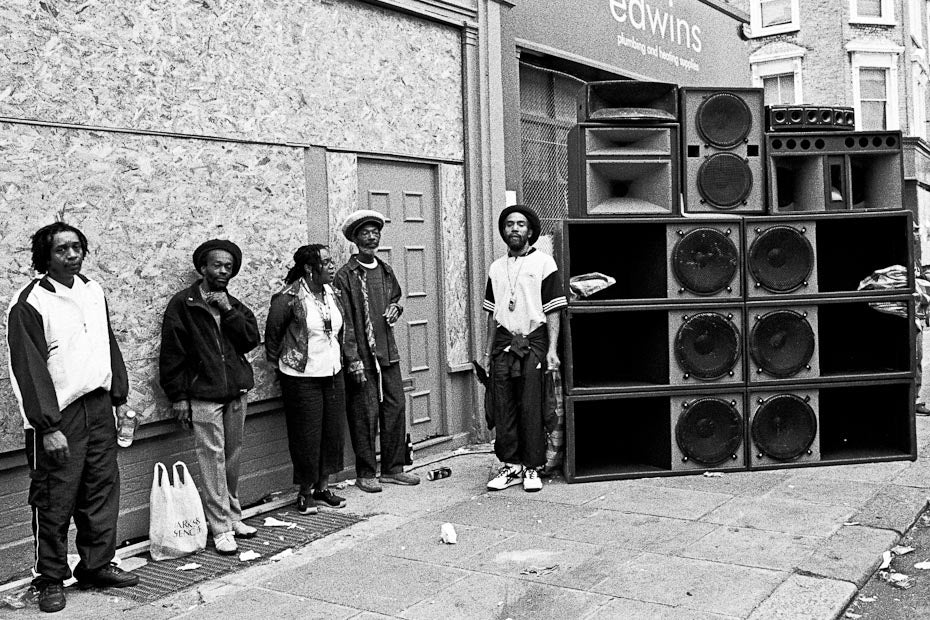

This paper advances existing work on spiritual landscapes by focusing on the affective experience of the roots reggae soundsystem. I show how the soundsystem creates a form of spiritual landscape by enabling the “performance, creation and perception of something unseen but profoundly felt” (Williams, 2016: 46 original emphasis; after Dewsbury & Cloke, 2009). Originating in Jamaica in the 1950s, soundsystems are musical assemblages that comprise mechanical systems of musical amplification (including turntables, speakers and a public address system) and their human operators (includingengineers, selectors/DJs and MCs). Essentially, they are mobile entertainment systems, providing audiences with the opportunity to experience a sonic environment that is “ethereal, mystical, conceptual, fluid, avant‐garde, raw, unstable, provocative, postmodern, disruptive, heavyweight, political [and] enigmatic” (Sullivan, 2014, p. 7), and to engage with the spiritual self. Whilst the work of Henriques (2003, 2011; see also D’Aquino et al., 2017) in particular has helped to build an understanding of the sonic dimensions of the soundsystem experience, the spiritual dimension has so far either been treated in cursory terms, or as an outcome of the social interactions brought about by the dancehall2 (see Järvenpää, 2015, 2016).

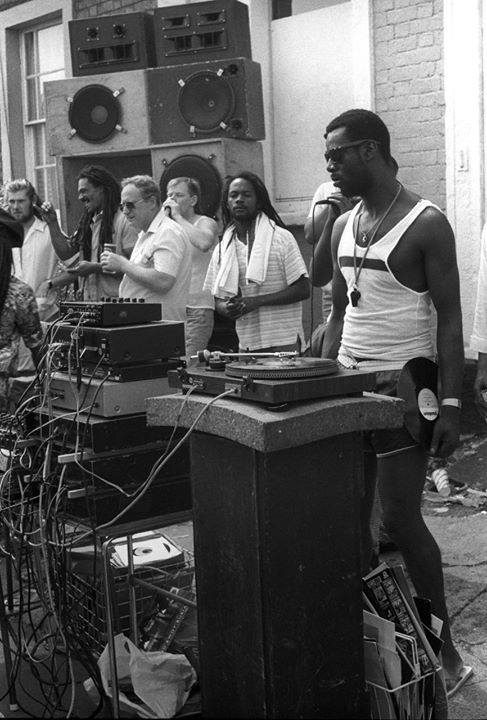

Often, it is also conflated with the Rastafari faith, although to do so is misleading. Whilst the roots reggae soundsystem may have originated from the Rastafari‐influenced musical culture of Jamaica in the 1960s, it has since attracted more broad‐based audiences and followers in Europe, North America, Japan and beyond. These audiences are drawn, amongst others things, to the “affective power” of bass‐driven roots reggae music, which, when listened to through a soundsystem, creates a “distinctly physical impact” (Jones, 1995, p. 7) that enables audiences to feel the sound through the body as much as the ears. It is the affective experience of sonic embodiment that renders the soundsystem a spiritual landscape with broad‐based, typically non‐religious appeal.From here, this paper is divided into three sections. The first provides a theoretical framework for investigating the interplay between sonic space and spiritual bodies. The second provides an introduction to roots reggae music and the role of Rastafari therein. The third is empirical in nature and explores the affective experience of the roots reggae soundsystem. It draws on an analysis of four documentary films (Dub Stories, 2006, directed by Nathalie Valeti; Dub Echoes, 2008, directed by Bruno Natal; Musically Mad, 2010, directed by Karl Folke; and Soul Rebel: Dub, Reggae and Soundsystem, 2013, directed by Percy Irie and Mighty Ital Studio) about soundsystem culture in general and reggae music more specifically.

My interest in the affective potential of sound originated in the early 2000s, when I used to attend weekly drum and bass events at the Fabric nightclub in London. Fabric has long been known for the quality of its soundsystems and, more uniquely, its vibrating “bodysonic” dance floor. This techno‐acoustic innovation involves transmitting low‐end bass frequencies through the dance floor itself, causing the music to be consciously felt through the feet and then transmitted through the body. Experiencing sound in such a way is profoundly impactful; it adds a new dimension to music and enables an appreciation of it in ways that cannot be accessed through listening alone. I elaborate on these processes below.

Over time, this interest evolved and expanded into the sonic affectiveness of soundsystem culture more generally, the spiritual affectiveness of roots reggae music more specifically, and the synergies that emerge when they intersect. Many of the ideas in this paper thus stem from my own affective experiences of roots reggae soundsystem sessions in London and Singapore, which have subsequently been validated and explained through the four documentary films.

The films are based on a series of interviews with a range of stakeholders, including globally dispersed reggae artists and producers of the music that is played, soundsystem owners and operators based in the UK and Amsterdam. This novel approach enabled me to access the views and experiences of difficult‐to‐reach stakeholders who are responsible for creating the affective experience of the roots reggae soundsystem. The interviews provided a holistic understanding of how the affective spaces of roots reggae music and soundsystem sessions are both shaped and experienced by the architects of those spaces. Many of the interviews involved a biographical element, which enabled me to gain an appreciation of the evolution of experience: from first impressions as an attendee of soundsystem sessions, to those of an artist now involved in the reproduction of roots reggae and soundsystem culture. The discussion of spirituality in/and the experience of the soundsystem emerged spontaneously, which serves to highlight its prominent role in soundsystem culture.

There is a meta‐value to this, as its unprompted discussion validates the fact that it is not an idea that I, as researcher, have imposed upon the interviewees, or led them to talk about through my questioning. Spirituality is discussed on the terms established by, and in the language used by, those who are responsible for creating the affective atmosphere of the soundsystem. Moreover, the emergence of spirituality as a spontaneous topic of discussion within each documentary parallels and, to a certain extent, reifies my argument that spirituality is something that comes from within; it is not an idea imposed from without.

Interestingly, whilst the interviews were mostly with males, only male interviewees discussed the spiritual dimensions of soundsystem sessions. This suggests that the affective experience of the soundsystem is a more masculine form of spiritual experience than is explicitly recognised by the interviewees themselves. Notwithstanding the above justifications for my approach, the fact remains that researching feelings, emotions and spirituality is inherently challenging and problematic. Echoing Wood et al.’s warning that few scholars “adequately account for how and why music works powerfully to shape [emotions and experiences]” (2007, p. 884, original emphasis), Mikey Dread, operator of the Channel One soundsystem, explains during the opening sequences of Musically Mad (2010) that:

Soundsystem is … I can tell you about, but you have to feel. You see, that is the nature of soundsystem. I can tell you about soundsystem from now until tomorrow morning, but you have to feel soundsystem to know what soundsystem is about.

Bearing this in mind, the views and experiences of people like Mikey Dread hold unique value in that they are the ones responsible for creating the environments in which such feelings are induced. They are not passive consumers of soundsystem culture, but are actively involved in its reproduction. They therefore provide an insightful vantage point from which new understandings of the spatial affectiveness of sound, and the spiritual affectedness of the body, can be forged.

2|SONIC SPACES, SPIRITUAL BODIES

Sound creates an affective atmosphere, which, in turn, can induce spiritual experience. Sonic spaces can be designed and curated through the positioning of speakers (or amplifiers), the diffusion of sound waves and the embodied experience of sound (see Gallagher, 2015; Gallagher et al., 2016). Sonic spaces play an important role in enabling such affective atmospheres, as they “allow us to block out rational processes, making the experience imminent, immediate and unmediated”(Henriques, 2003, p. 452). This section explores the theoretical framing of the interplay between sound and spirituality through three subsections. The first provides an overview of recent developments in the geographies of religion and shows how a focus on the affective experience of space and the sensory triggerings of spirituality can advance the subdiscipline. The second focuses more specifically on existing treatments of sensory experience and shows how decades of visual dominance have recently given way to an exploration of sonic media and knowledge production. The third provides an overview of existing work on the spatialities of sound, with a focus on its affective dimensions. The patterning of the subsections is somewhat circular; starting with religion, moving to the senses, then sound and space, before coming back to the notion of spiritual engagement. A holistic framework is therefore created, which is subsequently applied to an empirical analysis of the roots reggae soundsystem in the third section of the paper.

2.1 | The spiritual‐sensory turn in the geographies of religion

The geographies of religion are expanding in size and scope. In recent years, there has been a broad‐based shift from formal to more informal understandings of religion and spirituality. Whereas research was once dominated by the study of organised religions and the institutionalised praxis of religiosity, it has since given way to the exploration of more individualised interpretations and experiences of belief. This embrace of the “disruptive and unpredictable salience of the spiritual” (Dwyer, 2016, p. 758; see also Kong, 2001; Bartolini et al., 2016, 2017) is enshrined in Dewsbury and Cloke’s (2009) notion of a “spiritual landscape” and has yielded exploration of the everyday ways in which the spiritual becomes manifest – ways that often go beyond or reside outside of the formal prescriptions of religious spaces (Mills, 2012; Williams, 2016; Wigley, 2017; see also Holloway & Valins, 2002). Complementing this is an avenue of research that has adopted post‐phenomenological approaches to exploring the sensuous experience of the sacred by locating spirituality within the body (e.g., Holloway, 2003, 2006; Maddrell, 2013; see also Kong, 2010). Through this work, the body has been shown to have an active intelligence when sensing spiritual forms of affect and shaping the experience of the divine. Williams (2016, p. 46) for example, has demonstrated how a therapeutic community of recovering drug and alcohol addicts used Pentecostal worship practices to empower the body through various forms of sensory experience and, in doing so, to “open up, and close down, capacities and affective atmospheres of the divine.”

Most recently, research has taken the informal, everyday experience of a spiritual landscape and explored it within the more ad hoc framework of non‐fixity. Importantly, this has opened the discourse up to how the “affective registers of time and space” (Dwyer, 2016, p. 760) intersect with notions of religion and spirituality. Finlayson (2017, p. 304), for example, has shown how the sacred is “decidedly transient” and is only brought about through active processes of sacralisation in place, whilst Wigley (2017) draws on the new mobilities paradigm to show how spiritual praxis is not confined to codified religious spaces, but can also be conducted during the flows and movements of everyday life. In spite of these notable developments, exploration of the affective qualities of space remains “largely absent from the literature” (Finlayson, 2017, p. 307), as does a related focus on how different sensory experiences can either enhance or diminish such affectiveness (Williams, 2016; after Kong, 2001, 2010; Dewsbury & Cloke, 2009). I agree with these critiques and also contend that religion and spirituality are too easily and too often conflated, with spirituality typically being treated as an embodied response to religious belief. For example, Williams’s (2016) study locates spirituality within the framework of pre‐existing Pentecostal belief, whilst Wigley’s (2017) does so within a slightly looser framework of Baptist Christianity and Buddhism. To overcome the ascriptive impulses of religious belief, more work needs to be done to decouple spirituality from religion and explore it on its own terms instead.

Decoupling will open up possibilities for spiritual expression that go beyond the received authority of doctrinal religion and reveal a more sovereign sense of spiritual self‐realisation instead. I propose that whilst the body is mobile, constantly moving through the “affective registers of time and space” (Dwyer, 2016, p. 760), the spirit is located within the body and is therefore fixed. Every body has a spirit. This necessitates an understanding of the body as axis mundi, which, through the sensory experience of space, can engage with the spiritual self. Some spaces are more spiritually affective than others, just as some bodies are more spiritually engaged than others. What I am suggesting, therefore, is an embodied notion of spiritual essentialism – the idea that “all nature is capable of revealing itself as cosmic sacrality” (Eliade, 1959, p. 12). This idea finds meaning in Eliade’s original conceptualisation of hierophany – that of the “various and sometimes dramatic breakthroughs of the sacred … into the World” (1963, p. 6) – with my argument being that every body is capable of revealing its inherently spiritual nature under the right affective conditions. Just as Eliade suggests that hierophanies occur when the sacred reveals itself in place, I suggest that a sense of spirituality reveals itself in and through the body as an embodied hierophany; and, just as Eliade suggests that sacred space marks a point of departure from everyday, profane space, I suggest that the realisation of the spiritual body marks a point of departure from the everyday, profane body.

Spirituality becomes manifest through the decoupling of the body from rational thought and action, and the revelation of more uncontrolled and profound forms of feeling instead. Such forms are often synchronous with the affective experience from which they stem, which means that different sensory experiences can result in different forms of spiritual engagement. The body plays a pivotal role in mediating these transitions and in revealing the spiritual self. In the context of a roots reggae soundsystem session, the body becomes the sound through movement – a process that can induce feelings of transcendence and detachment from the profane self. To explore these ideas further, research needs to develop an under-standing of how the active intelligence of the body, as it moves through the affective registers of time and space, can engage this sense of spirituality outside of any pre‐existing (or associative) religious frameworks. Doing so will lead to a greater understanding of the spiritual body and how it may enforce, subvert or otherwise operate independently of religious belief. To do so, there is a need to overcome the longstanding dominance of visual forms of knowledge production and to embrace alternative sensory‐based epistemologies instead.

2.2 | Overcoming the sensory hierarchy

As a legacy of the Western philosophical tradition, the senses tend to be organised hierarchically, with the visual often privileged. The visual has provided a foundation for knowledge (Henriques, 2003, 2011; see also Jones, 1995), with images and words being the basis for the sacred texts that underpin most world religions. Such visual dominance reflects and reinforces the fact that “the West” follows a primarily visual culture, which in turn has led to the marginalisation of other sensory traditions. Overlooking the possibilities for an “epistemological matrix coded not in words but in sound” (Chude‐ Sokei, 1994, p. 80; see also Radcliffe, 2017) serves to reproduce the colonisation of knowledge production by the Western academy. Importantly, such sound‐based matrices are resonant in parts of Africa, which provides a cultural grounding and point of sonic reference for reggae music. In recent decades, the mind/body dualism that results from such privileging has been critically interrogated by geographers, which has led to an understanding and appreciation of more embodied forms of intelligence and knowing (see Anderson et al., 2005; Falk, 1994; Rodaway, 1994; Wilson, 1998). This has given way to a more focused consideration of sound‐based epistemologies.

Within geography, there has been a growing appreciation of the value to be derived from sound. Whilst there has been a growing interest in the geographies of music (after Kong, 1995; Smith, 1997) and associated soundscapes, recent calls to rebalance the textual bias by embracing more listening‐based methodologies (e.g., Gallagher & Prior, 2014; Gallagher et al., 2016; Woods, 2018; see also Wood et al., 2007) highlight the ongoing need for redress. Indeed, as Rose (1993, p. 86) observed nearly a quarter of a century ago, “the visual is central to claims to geographical knowledge,” resulting in situations whereby “seeing and knowing are often conflated” (see also McCormack, 2003). This foregrounds the shift towards exploring more sensuous experiences of the sacred by geographers of religion and reveals the expansion of epistemological horizons that can arise from exploring the affective nature of sound. Whilst the visual is typically rational and cognitive, the sonic is typically irrational, emotive and embodied (after Henriques, 2003, 2011) and can therefore open up new avenues for understanding the nature and extent of non‐representational spiritual experience. Indeed, Henriques goes so far as to suggest that the verb sounding is a more accurate way to describe the agency of sound as “kinetic activity, a social and cultural practice, a making and becoming” (2008, p. 219; after Lastra, 1992; see also Small’s, 1998 notion of “musicking,” which encapsulates the practices of taking part in musical performance). The process of sounding is a spatial phenomenon and leads to the creation of sonic spaces.

2.3 | The spatial affectiveness of sound

Sound travels through space and it creates it as well. In contrast to the ambient noises of everyday life, sonic spaces are “specific, particular, and fully impregnated with the living tradition of the moment” (Henriques, 2003, p. 459; after Augé, 1995). The spatial modalities of sound have been advanced by scholars of cultural and sound studies (see, for example, Augoyard & Torgue, 2008; Camilleri, 2010; Henriques, 2011; LaBelle, 2006, 2010), with geographers also contributing understandings of how music can enable various forms of socio‐spatial connection and intimacy (Saldanha, 2003, 2005; Wood et al., 2007; Woods, 2018; see also Gallagher & Prior, 2014; Gallagher, 2015).

Consolidation of the field of “rave studies” in the 1990s brought about a more sustained focus on the presence of religion and spirituality within musical sub-cultures (see St John, 2003, 2006). Research has since explored how such subcultures carry “traces of the spirit” – often through the achievement of transcendence or a “natural high” (e.g., Saldanha, 2003; Takahashi, 2003; Takahashi & Olaveson, 2003) – and function “in the same way as a religious community, albeit in an unconscious and postmodern way” (Sylvan, 2002, pp. 4–5; see also St John, 2006). Notwithstanding the value of such work in unravelling the intersections of music, affect and religion, it has failed to advance more theoretical engagement with the spatial affectiveness of sound and the ensuing possibilities for spiritual connectivity.

More instructive for the purposes of this paper, therefore, is consideration of the ways in which sound intersects with both the body in space and the space of the body. Such a recursive relationship between the body and sonic spaces has been articulated as being “inside you as well as you being inside it” (Henriques, 2003, p. 459). The porosity of the boundary between the acoustic space outside the body and the space within therefore causes individuals to experience sound in an embodied way. The notion of an embodied experience of sound is replete with opportunities for the listener to explore new forms of becoming, as the “materiality of the body” enables “the becoming of new spaces of musical possibility” (Wood et al., 2007, p. 873). The outcomes of such exploration can help to unlock new understandings of the self and can pave the way for spiritual connectivity. As Wood et al. (2007, p. 873) explain, “the immersion of our bodies within music problematises the experience of self as separate and individualised; sound passes through and into the body, making personal boundaries porous and emphasising the sociality of self.” Beyond sociality, “immersion” can enable the spiritual self to manifest, a process that goes beyond listening and involves more subtle and profound sensations of feeling as well. For example, Henriques (2003, p. 460) explains how sound travels as a vibration and as these vibrations encounter and enter the body, they create an affective experience: “you feel both the air as the gaseous liquid medium that “carries” the sound and hear the waveform of the shape of the sound” (original emphasis; see also 2016).

Some sounds are, however, more affective than others. The affective potency of sound is contingent upon both the listener’s (or experiencer’s) personal tastes and encultured sensibilities and the “spatial musical structure” (Otondo, 2007, p. 12) that defines its rhythm and timbre. The sounds and rhythms of music thus forge a “nonverbal signifying system; they express precisely what we cannot express in language” (Wood et al., 2007, p. 883). The effect of such non‐verbal significance is that it can translate into embodied forms of knowledge, experience and understanding (see, for example, Saldanha’s (2005, p. 707) discussion of how Goa’s rave scene brings about “mysterious effect[s] on the body”). Reggae is a rhythm‐dominant musical genre; the emphasis on an offbeat, bass‐heavy ostinato has been recognised as rendering it infectious in its transmission through space and into the body (Browning, 1998; Henriques, 2008). The feeling of rhythm has been theorised by Roholt (2014) as “grooves,” with the embodiment of grooves creating new forms of understanding that can circumvent mental processes of cognition. The body is therefore able to know through movement a priori what the mind seeks a posteriori. Grooves – rhythms – situate the listener within their own body, creating new experiences that the mind is always trying to understand and rationalise. Thus, the feeling of a groove is the “affective dimension of the relevant moto‐intentional movements” (Roholt, 2014, p. 105; after Merleau‐Ponty, 1964); the channelling of motor skills to achieve a particular end. It is in this sense that sound “moves as an affect,” and whilst sound has been shown to “mov[e] people to feel that they have a connection with other people and other places” (Henriques, 2008, p. 216; see also Wood et al., 2007; Overell, 2014), I go further and suggest that the affective experience of sound can create a sense of spiritual connection as well. Such connections are often built on an extreme experience of sound – through either its unavoidable presence or absence.

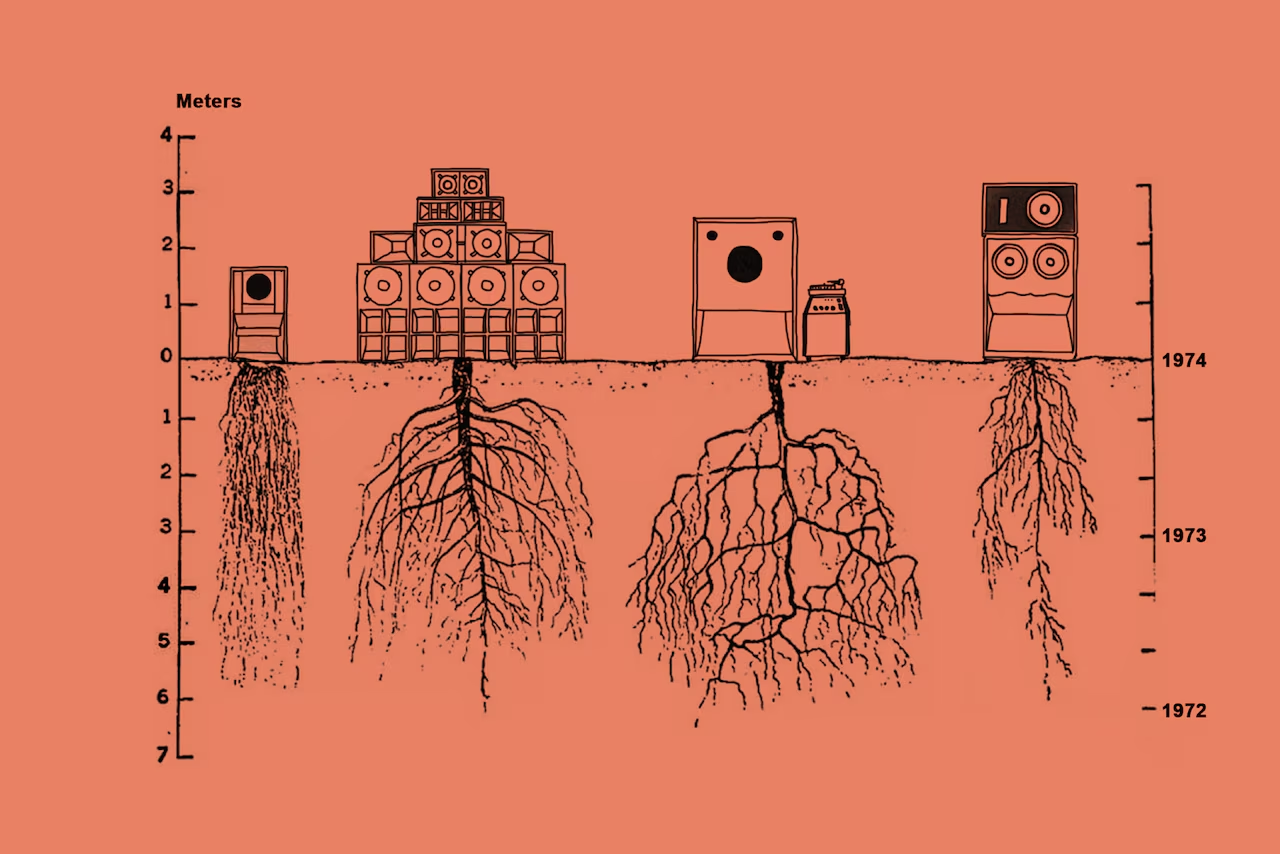

Extreme forms of sound are closely entwined with spiritual engagement, with overload and underload representing two poles of sensory experience. Both circumvent processes of rational cognition. Sonic underloading is the creation of absolute silence through the removal of sound. Meditation techniques, for example, rely on the sensory deprivation associated with underloading to bring about experiences of hallucination and out‐of‐body floating (Henriques, 2011). Conversely, sonic overloading is the creation of a state of hyper‐stimulation through the (excessive) amplification of sound. It is about creating a situation of sonic dominance that, through the violence of sensation, creates ‘grounding “into body” experiences’ (Henriques, 2003, p. 458) that cause the body to assume an involuntary intelligence that the mind often struggles to comprehend (after Deleuze, 2003). Sonic overloading can make bodies “quiver with affective energy” (Thrift, 2004, p. 57); they become a “grounded orientation point” (Dewsbury & Cloke, 2009, p. 700; see also Kong & Woods, 2016) through which the ineffable can be experienced and the spiritual can become manifest. The fact is that spiritual experience is an intuitive, sensual and visceral phenomenon, and sonic overloading (and underloading) creates the conditions through which it can be realised. Sound can therefore “open out spaces that can be inhabited, or dwelt, in different spiritual registers” (Dewsbury & Cloke, 2009, p. 696), with the spiritual landscape of the roots reggae soundsystem creating an affective atmosphere through which the spirit of every body can be engaged.

3|THE RASTAFARI ROOTS OF REGGAE

Any discussion of the spiritual dimensions of a roots reggae soundsystem must recognise the religion with which it is most closely associated – Rastafari. Rastafari emerged in the 1930s in Kingston, Jamaica as a breakaway sect of Revival Zion, an indigenous form of Christianity. It started as a socio‐religious movement that engaged with issues of pan‐African internationalism and Afro‐Caribbean anti‐colonial resistance. It recast black people (irrespective of nationality or origin) as Ethiopians and hailed the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie as a divine saviour of black people around the world (Chevannes, 1994; Järvenpää, 2015, 2016). Over time, Rastafarians developed a range of practices and taboos – such as the growing of dreadlocks, the sacramental use of cannabis, a politicised patois and the following of an ital3 diet – that have since come to define the group in the popular imagination. Since the 1960s, many of these practices and taboos provided a point of crossover into Jamaica’s burgeoning music industry, with Rastafari becoming an integral component of the musical (and cultural) aesthetics of reggae music. Indeed, many of reggae’s most famous musicians – including Bob Marley, Winston Rodney, Horace Andy, Augustus Pablo and Max Romeo to name but a prominent few are/were Rastafarians, causing religious influence to permeate their music and lifestyles. Over time, as reggae music metamorphosed into more contemporary strains of ragga, dancehall and dub(step), its Rastafari origins have become enshrined in a specific subgenre known as roots reggae (see Järvenpää, 2016; King, 2002).

As Jamaica’s music industry developed, so too did its soundsystem culture. The soundsystem is not just the acoustic environment created by amplifying sound through subwoofers and woofers, midranges and tweeters, but also the medium through which the latest music could be shared amongst audiences (Henriques, 2008; Veal, 2007). It exemplifies the sound culture of Jamaica and the Jamaican diaspora – soundsystem owners and operators have the power to shape their sound to suit their music, thus enhancing the affective experience. Not only that, but the soundsystem is most commonly associated with roots reggae music; it is the medium through which the “driving bass and drums of reggae ‘riddim’”4 (Chude‐Sokei, 1994, p. 80) could be shared with live audiences, along with a politico‐spiritual message rooted in the pan‐Africanism of Marcus Garvey. The flexibility of the soundsystem is not limited to its acoustic arrangement, but extends to its mobile nature as well. Soundsystems are not tied to specific venues; instead, they are a “peripatetic, highly mobile, circulating nomadic institution” (Henriques, 2003, p. 454) that, like the music they play, move through space. The soundsystem was introduced to the UK in the 1970s with the arrival of Jamaican immigrants and the ensuing formation of the Jamaican diaspora in London and other urban centres. Since then, it has spread to Europe and beyond.

Soundsystems create spaces of connection. They have been shown to connect people across national, social and ethnic boundaries (see Gilroy, 1993; Hesmondhalgh & Melville, 2002; Järvenpää, 2015, 2016; see also D’Aquino et al., 2017),yet there has so far been little consideration of their spiritual connectivity, or their ability to align the body with the spirit.Indeed, the diffusion of soundsystem culture around the world has caused its Rastafari influences to become diluted; whilst many soundsystems are owned and operated by Rastafarians, they typically attract majority non‐Rastafarian audiences. For most, attending a soundsystem session is a cultural experience. In a similar vein, whilst roots reggae music contains a strong religio‐political message (the “music message” – see below) relating to issues of justice, truth and rights (Chevannes, 1994; Järvenpää, 2015), the music itself is just one aspect of a much more enveloping affective experience. This distinction is important. Whilst the roots reggae soundsystem may have a grounding in Rastafari, the spiritual experience is not limited to Rastafarians, or any other religious affiliation. Indeed, the opposite is true; it attracts people from all walks of life, professing any or no religious belief. Järvenpää, for example, shows how reggae sessions in a township in Cape Town, South Africa, are mostly attended by non‐Rastafarians as they are “more inclusive than explicitly religious Rastafarian ceremonies” (2015, p. 6; see also Chawane, 2012). The soundsystem therefore creates an affective atmosphere that is conducive to spiritual engagement, which itself is distinct from Rastafari religious practices.

4|THE AFFECTIVE EXPERIENCE OF THE ROOTS REGGAE SOUNDSYSTEM

Having provided an overview of the spiritual‐sensory turn in the geographies of religion, the visual dominance of knowledge production, the spatial affectiveness of sound and the role of Rastafari in the genesis of reggae music, I now apply these ideas to the affective experience of the roots reggae soundsystem. In doing so, my intention is to build on Barthes’ (1985, p. 245; original emphasis) well‐rehearsed distinction between “hearing [a]s a physiological phenomenon; listening [a]s a psychological act” by suggesting that experiencing sound is an affective process that can open a person up to new forms of (spiritual) becoming. I do this by exploring three co‐constitutive aspects of the roots reggae soundsystem, which can be summarised as the stimulus, the channel or medium and the effect. The stimulus refers to the music that is played on the soundsystem – specifically, roots reggae and dub; the channel or medium refers to the soundsystem itself as a transmitter of music and creator of sonic space; and the effect refers to the affective experience of the soundsystem and the creation of embodied hierophanies. Through the analysis of interviews conducted with soundsystem operators and music producers from four documentary films, these three aspects are expounded in the sub‐sections that follow.

4.1 | The music message and the affective spaces of dub

Roots reggae is one half of the musical equation that is played through soundsystems; the other is dub. Whilst roots reggae music includes a vocal and harmonised musical arrangement, dub involves stripping away the vocal and harmony, and emphasising and distorting the riddim through the use of various sonic effects such as reverb, echo and delay. Whilst roots reggae music is typically recorded by a band or artist in a studio, dub is created by a music producer and mixing desk.

During a soundsystem session, both the original version (the A‐side) and the dub version (the B‐side) are played sequentially, as explained by recording artist Alpha Roots:

The A‐side of the record is the message, and it gives you something to think about, and then the B‐side is the dub version, which gives you some time, personally, for some meditation, and to think about what that mes- sage was. (Soul Rebel, 2013)

The A‐ and B‐sides therefore play complementary roles. The A‐side, with the vocal and full instrumental, is the “message,” which is often rooted in Rastafari teachings and ethno‐political consciousness. Exhortations to praise Jah,5 to continue the struggle for justice and equality, and to overcome oppression and sufferation, are common. Such messages often provide critical commentary on topical issues and seed ideas of socio‐spiritual awakening for listeners (Dawson, 2002; see also Gilroy, 1993). This blend of religious and political messages often finds broad‐based appeal and resonance (especially amongst the socially dispossessed and politically marginalised – see Sterling, 2010; Järvenpää, 2016), as explained by UK‐based music producer, Russ Disciples:

Like I said, I’m not a Rastaman, but there’s a spiritual thing going off still, you know? And there’s a teaching thing with the music, and a learning thing, and a message thing, you know, which I hope people will take in and kind of understand, you know? … It’s just like ‘listen to it, and see how you feel about what these guys are singing about,’ because even if it’s about Jah and Rastafari, it doesn’t necessarily mean you have to start locks up [i.e., grow dreadlocks], you know … But you can be a spiritual person and deal with love and unity and honesty and good vibes and that kind of stuff. (Musically Mad, 2010)

Russ Disciples’ comments reveal the sort of spirituality – the “spiritual thing” – that is commonly associated with the soundsystem experience. It is a form of spirituality not overtly linked to religion (or, in this case, Rastafari), but more to do with a process of introspection that involves “meditation” or inward reflection on the self. This notion of spirituality – of cutting through to the essential core of the self – is triggered by the message (the “teaching thing” and the “learning thing”) of roots reggae music.

If the A‐side provides the ideas, the mental stimulation that can provide a precursor to spiritual awakening, then the B‐side provides space for reflection. Dub is repetitive, tribal music that enables reflection on the vocal message. Playing the two sides of a record sequentially enables “you [to] get the chance to reflect, and then you keep reflecting because you’re staying in that repetition” (JT, operator of the Kibir La Amlak soundsystem, Soul Rebel, 2013). Repetition is an enabler of affective experience, as it creates a cyclical feeling of solidness or consistency. The power of the riddim is that it “lifts you out of yourself, there’s a repetitive sense to it that’s hypnotic, that takes you over” (Brian Nordhoff, sound engineer, Dub Echoes, 2008). This facilitates the process of decoupling the self from rational thought and action, and provides the basis from which inner exploration can begin. Music producer, Howie B, explains how “repetition, I think, is a platform for freedom, you know. It means you can jump, you can jump, yet I know that beat is going to be there when I fall down” (Dub Echoes, 2008). Looking beyond the metaphor, repetition provides a sort of metaphysical crutch that enables the listener to explore their sense of self (“it means you can jump”). The sound of dub music can therefore yield a variety of “indirect implication[s]” that occur when “the listeners start to use their imagination and their own experience to find a place in the music” (Otondo, 2007, p. 14). Musician Brother Culture explains how the B‐side is:

A space where we put our mind, that is what dub essentially is. It’s something that can be interpreted by different people, different times, because it puts the power of interpretation back with the audience … The audience sort of create their own reading. (Dub Stories, 2006)

The significance of “put[ting] the power of interpretation back with the audience” is that it renders the experience of roots reggae music truly emancipatory. It provides a trajectory and ideas, but no prescription; the feeling of the spirit is self‐directed. Spiritual realisation is therefore “invented in sound by the open metonymic spaces of heavy dub echoes” (Chude‐Sokei, 1994, p. 80). Thus, whilst the music of roots reggae provides the stimulation needed to engage the spirit, the soundsystem provides the affective atmosphere through which it can become manifest.

4.2 | The spiritual landscape of the soundsystem

Soundsystems are built to deliver bass‐heavy music. They are, in other words, built to deliver an immersive sonic experience that is based on the principle of overloading. Henriques (2003, p. 452) uses the term “sonic dominance” to describe situations when sound “has the near monopoly of attention” and thus displaces the usual dominance of the visual. He goes on to explain the experience6 of sonic dominance in more detail:

The first things that strikes you in a Reggae sound system session is the sound itself. The sheer physical force, volume, weight and mass of it. Sonic dominance is hard, extreme and excessive. At the same time the sound is also soft and embracing and it makes for an enveloping, immersive and intense experience. The sound pervades, or even invades the body, like smell. Sonic dominance is both a near over‐load of sound and a super saturation of sound. You’re lost inside it, submerged under it … There’s no escape, no cut‐off, no choice but to be there. (Henriques, 2003, pp. 451–452)

The experience is intense, almost oppressive. Yet, despite the volume and weight of noise being produced, it is also a very intimate experience. Rather than projecting music outwards, onto the audience, speaker stacks are arranged so that they encircle the audience, projecting the music inwards. This creates a sort of sonic cocoon that envelopes the audience. The selector (or DJ) mediates the experience, engaging the audience through exhortations, call‐and‐response exchanges and dedications, and controlling the “psycho‐acoustic space of the dancehall” (Chude‐Sokei, 1994, p. 82). Whilst playing music, the selector (or an accompanying MC) provides an intermittent form of musical commentary, delivered as “disembodied voices which evoke impressions of omnipresence and omnipotence” (Järvenpää, 2015, p. 20). This draws a clear parallel with the Judeo‐Christian tradition of linking voices with revelation and feelings of spiritual ecstasy. The spiritually affective atmosphere is created and maintained through other forms of sensory stimulation as well. JT, operator of the Kibir La Amlak soundsystem in London, explained how “often the dance is quite dimly lit, so it adds to the meditative vibe. When Kibir La Amlak play, we always burn frankincense, again to try and add to that meditative vibe” (Soul Rebel, 2013). Combined, the dim lighting, the burning of frankincense, the rhythm, structure and composition of roots reggae music and the sonic dominance of the soundsystem create a unique sensory environment that can open up the audience to new forms of (spiritual) experience.

The soundsystem experience is an embodied experience. Soundwaves are felt and translated into rhythmic pulses by the body, a process that is amplified in a soundsystem environment. Bass‐heavy music is powerful; to produce bass, air is literally thumped out of a subwoofer, creating a physical moment of impact with the body. When talking about bass, the experience moves from listening to feeling; from sound to vibrations, as “the wave form is so slow that the ear isn’t picking it up, but the body is, and it’s moving the body” (Brian Nordhoff, sound engineer, Dub Echoes, 2008). Bass is about the body more than it is the ears or the mind; it “touch[es] you and connect[s] you to your body” (Henriques, 2003, p. 452; see also Duffy et al., 2011), thus creating a sense of “immersive whole‐body listening” (Henriques, 2008, p. 224). The primacy of bass forces the body to surrender to the affective dominance of sound, a dominance that at once evokes power and pleasure. Understanding the embodiment of bass is important, as this is what enables spiritual connection. The transition from a corporeal, sensory experience to a more profound form of spiritual experience is explained by DJ Stryda of musical duo Dubkasm:

You hear a lot of talk about bass music in this day and age … And that is a huge part of soundsystem, you really feel it in your chest and stuff, but then there’s so much more to it, and I think that some people who might initially come for the bass vibe, they, actually, when they go a bit deeper by repeatedly going to soundsystem sessions, they start to listen to the wordsound and feel the power in the message as well, not just the powerful bassline. And also feel the atmosphere and energy that’s created in a roots reggae soundsystem event, which is something quite unique and special … There are different opinions as to what is spiritual and stuff, but I think, myself, and many friends in the scene, have been really uplifted at a soundsystem event, and reached a real high. (Soul Rebel, 2013)

This interplay of sonic dominance and spiritual engagement creates a paradox that simultaneously involves surrendering the body to the power of bass whilst freeing the mind for reflection and internal discovery. Henriques (2003, p. 468) describes this as the “transcendence” of sound, which results in vertical connections (or “upliftment”) to a higher sense of purpose or realisation. The interplay between sonic dominance and affective experience is explained by Simon Ratcliffe of electronic music duo Basement Jaxx:

When I came to London … I started going to Jah Shaka soundsystems, and then, you know, that was it. I was addicted … It was quite a spiritual experience … You were in a club in a way, and you were listening to this big, loud music, but it wasn’t, it was a place of reflection, you know? It was a place where you could almost meditate. And you really got absorbed by the music. (Dub Echoes, 2008)

The soundsystem is a form of spiritual landscape, which, through sonic dominance combined with the message of roots reggae and the repetitive riddims of dub, enables the audience to retreat into themselves. Such engagement with the internal self – the spiritual self – manifests in various ways, which will now be examined through a consideration of embodied hierophanies.

4.3 | Transduction and embodied hierophanies

Soundsystems have a strong spiritual quality that is nurtured and encouraged by the music (stimulus) and its delivery (via the soundsystem). Whilst spiritual engagement is not necessarily realised by all who attend a soundsystem session, the soundsystem creates the conditions through which a person can engage their spiritual self. These conditions have been theorised by Henriques (2003) as “transduction” – the process of crossing a boundary and bringing about some sort of change. Materially, a loudspeaker is a transducer that converts energy from one form to another. Electromagnetic coils are used to move the diaphragm of the speaker, creating a pulsating movement that creates wave after wave of sound that can be heard. Microphones operate in a similar way. Beyond such techno‐material examples, there are also the embodied aspects of transduction. At a soundsystem session, the body becomes a form of sensory transducer:

At its simplest a musical bass line provokes the kinetic movement of tapping your foot to the rhythm. This occurs automatically and without thinking about it, as a bodily rather than a rational response. It’s a transformation [of] sonic energy into kinetic energy. (Henriques, 2003, p. 468)

This almost involuntary sense of movement is a function of the bass frequencies described above. Beyond materiality and corporeality, transduction can also be used to explain the spiritual engagement brought about by the soundsystem. Just as transduction connects energy to sound, and sound to movement, so too does it connect the body to the spirit. More than connection, transduction translates the embodied feeling of sound into spiritual energy; a sense of spiritual liveliness that is awakened by the affective atmosphere of the soundsystem. The sensory experience of sound can create the conditions needed to awaken a sense of latent spirituality within attendees, which manifests as an embodied hierophany. King Shiloh,operator of the King Shiloh soundsystem in Amsterdam, explains such embodiment as validation of his view that “reggae is inside all of us, do you know what I mean? We just need a reaction … to make us realise that, right?” (Dub Stories, 2006). Recording artist Alpha Roots affirms such sentiment, but goes a little further when explaining how “reggae music is within all of us, the riff pattern is like the beat of our heart, you know?” (Soul Rebel, 2013). In recognising that reggae is “within all of us … like the beat of our heart” and awakened by the soundsystem experience, we can see how processes of transduction have the potential to “transcen[d] the dualities of form/content, pattern/substance, body/mind and matter/spirit” (Henriques, 2003, p. 469), whilst remaining responsive to the dictates of individual experience. Soundsystems create a liminal space that parallels the experiences of glossolalia or voodoo; forms of inspirited worship that circumvent the cognitive experience of religion by making sensory connections with an intrinsic sense of spirituality instead.

The power of the soundsystem lies in the fact that it can uplift the audience, enabling it to transcend the mundane, everyday world and enter an elevated state of experience. Soundsystem operators are the architects of such experiences, responsible for creating the affective atmosphere through which the spirit can be engaged. This creates an atmosphere of inclusiveness, one that “brings everyone together in a way that other music doesn’t” (Alpha Roots, Soul Rebel, 2013). The ostensibly non‐religious nature of the soundsystem renders it a spiritual landscape that transcends the boundaries of religion or belief. The affective atmosphere is predicated on the creation of what is commonly referred to as “vibes,” with “good vibes” often indicating an atmosphere that is conducive to inclusiveness and spiritual realisation. Recording artist Afrikan Simba shared how people would tell him that “I feel different coming out of that sound; I feel that that all my problems have gone, my shoulders feel light, like I was carrying something and it’s gone” (Musically Mad, 2010). The creation of “vibes” is the cumulative effect of various factors, including the music selection, the sound quality and the responsiveness of the audience. JT of Kibir La Amlak explains why creating such an atmosphere is so important to him as a soundsystem operator:

Kibir La Amlak is an Amharic term, which means “Glory to Jah”. So, this is really the essence of what we bring when we play. But in terms of giving glory to Jah, it’s giving glory to Jah through the experience of appreciating the divine qualities of music and rhythm and wordsound via the soundsystem experience, which is the sharing experience. And that can bring about different sorts of meditative states, it can bring about a sort of cathartic experience, where you’re in that sort of intimacy of the soundsystem and the sharing vibes, it consciously is giving people the freedom of expression to really free up themselves. (Soul Rebel, 2013)

The desire to give “give people the freedom of expression to really free up themselves” often results in a style of dancing known as “skanking.” Skanking is typically expressed through the rhythmic stomping of the feet, a forward‐backward rocking motion and the outward extension of the arms. As much as it is a physical act – Henriques (2008, p. 230) describes the “flat‐footed stamp” as “emphasis[ing] their earthly connection” – it is also part of the meditative act of spiritual engagement. For example, Järvenpää (2015, p. 14) observes how skanking involves audiences being “lost in their own thoughts,” which shows how the physicality of skanking can be interpreted as the embodied manifestation of hierophany. These ideas are taken further by soundsystem operator and musician, Ras Terry Gad:

I get my vibes from the music, and it’s the vibes of the music, it’s a very deep, conscious music, reggae music, roots music, and it’s very spiritual, and I move in the way that the spirit wants me to move. That’s why I jump and skank, you know? However the music wants me to move, I move. (Musically Mad, 2010)

As manifestation of an embodied hierophany, skanking is an encultured response to the spiritual energy that is created through the soundsystem experience. It is an expression of “ritual dance and spirit possession” that is triggered by “repetition of the beat for an extended period of time, and its rupture, so that dancer can lose consciousness” (Järvenpää, 2015, p. 21). Combined, the message of roots reggae and the affective spaces of dub, when delivered through the spiritual landscape of the soundsystem, enable processes of transduction that cause embodied hierophanies to become manifest. More than that, for many attendees, the soundsystem enables a sense of spiritual connectedness that exists beyond the boundaries of religion and feelings of transcendence that mark a departure from the everyday, profane self.

5|CONCLUSION

This paper opens with a quote by dub music producer and sound engineer, Mad Professor. It refers to the relationship between a record and the dub version of the record; between the A‐side and the B‐side respectively. The record is the object, the dub version is the shadow that needs to be “found” by the producer. This metaphor is instructive for the understanding of spirituality advanced by this paper; every body has a spirit, it just needs to be found or discovered. As I have shown, one way of discovering it is through the affective experience of the roots reggae soundsystem. A broader point is that spirituality, like dub music, is about stripping away thought and cognition, and embracing the essence of the self. Dub does this by removing the vocal and accentuating and distorting the riddim; the soundsystem does it by providing an affective experience that overrides cognition and induces a sense of embodied hierophany instead. It enables meditation, which in turn enables a profound sense of connection to the spiritual self. The spiritual dimensions of the roots reggae soundsystem lie as much in the religious framework of Rastafari as they do the sonic experience and affective outcomes of roots reggae music (after Chude‐Sokei, 1994). Thus, whilst the affective experience of the soundsystem is rooted in Rastafari cultural practice, its effects go far beyond the prescriptions or dogma of any formal sense of religious belief.

By developing a new perspective on the sensory triggers of spirituality, this paper has helped to advance the geographies of religion in various ways. As part of the spiritual turn (Bartolini et al., 2016; after Holloway & Valins, 2002; Holloway, 2003), it has developed a new perspective on spirituality (as an embodied phenomenon that is latent within every body) that is rooted in the conceptualisation of an embodied hierophany. This recycling of Eliade’s (1959) term shows how reframing existing thought through a spiritual lens can help to revive, refresh and enrich old perspectives and, in doing so, advance new ideas. More than that, however, is the focus on sound as a spiritual trigger. By bringing the geographies of religion into conversation with existing thought surrounding (the spatiality of) sound, I have not only shown how the cross‐pollination of ideas can help to enrich geographical discourse, but also how much more work needs to be done to overcome the existing bias that privileges the visual over other forms of sensory experience (after Williams, 2016).

To this point, this paper raises two areas for further investigation. The first concerns the relative influence and affect of different sensory experiences (olfactory, haptic, gustatory) on spiritual experience, however defined. Relatedly, further work is needed to explore the relationship between movement and spirituality. I have shown how skanking is an outcome of spiritual engagement, yet more work can be done to explore how the body channels the spirit through (non‐)movement in and through space. The second is more specific and relates to the affective experience of the soundsystem in different (religio‐cultural) contexts around the world. As mentioned above, soundsystem culture originated in Jamaica, but has since moved and settled around the world. The empirical data used in this paper derive from Western European (mostly British) perspectives; yet, we can expect the processes of spiritual transduction to differ around the world. The largely secular context (and audiences) of Western Europe may, for example, lead to a situation of greater spiritual openness than in parts of Latin America or Asia, where soundsystem cultures also prevail. How the experience of soundsystem culture around the world brings about processes of spiritual translation and adaptation to suit different (religious) contexts will yield important insights into the interplay between religion and spirituality, and between formal and informal spiritual praxis.