Interview with Sir Lloyd Coxsone

http://uncarved.org/dub/splash/coxsone.html

https://www.factmag.com/2015/09/02/sir-coxsone-outernational-interview/

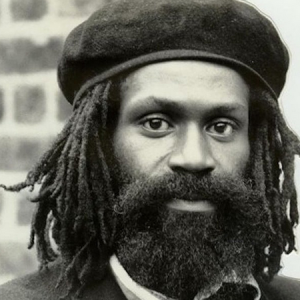

Lloyd Blackwood better known as Sir Lloyd Coxsone, a tall slim man hailing from Morant Bay, arrived in England in 1962. Since his arrival Coxsone has been based in South West London and has been involved in the subterranean network of blues and sound system dances in that area. Then Coxsone has becomed the sound against which all others are judged, becoming an influential figure in the growth of the UK reggae scene and sound system culture and business. He says “it is a good business” will also concede “it is a hard life, uncertain. . . today up, tomorrow down. We have been up and down many times but we have experience. To run a good sound in the UK is teamwork… a young team of men who are ambitious, record crazy and have young ideas, If I get old within my ideas there is many young men who come up with suggestions. By building a team you are building your sound for a long term. In my time in England I have seen a lot of good sound die ‘cause they didn’t build a team to manifest the work of the sound. Teamwork and effort is crucial as you can’t live off your name.”

During the mid-80s Coxsone handed control of his sound over to the younger elements in his team, notably Blacker Dread, and a new breed of DJs. Blacker released his own productions by the likes of Fred Locks, Frankie Paul, Mikey General, Sugar Minott, Michael Palmer, Don Carlos, Earl Sixteen. Recently, as interest in the roots music of the 70s has increased, Coxsone has emerged from his semi-retirement to stand again at the controls of his sound.

Lloyd Coxsone sound was the first UK system to play dub, that they set the pace in equipment and pioneered the use of echo, reverb, equaliser, and also in paving the way for a sound system such as Shaka to take sound to a new dimension, creating atmosphere out of rhythmic weight and effects. Sound system has come a long way since the days of Lloyd the Matador, Coxsone first sound system, when upon asking an electronics man named Fred to build him a 600 watt amp, Coxsone was greeted with: “You must be fucking crazy. Do you know how much power it takes to drive a cinema? Ten watts!” The past 15 years has seen a shift from one extreme to another, and the banks of amplifiers in evidence at any sound dance are testimony to the current fixation with wattage rather than, Coxsone feels, an ability to select and present the music. “People can’t dance to wattage. If a man comes to me and he deals with sound he almost always deals with wattage. Listen, the more you step up weight you lose quality, and a man must be able to hear your vocal playing. Too much sound in this country is running down weight, but I don’t see sound as is rootin’ down like bulldozer as good sound. I am more interested in quality and selection of music.”Different philosophical attitudes result in different approaches. Those who have witnessed Shaka and Coxsone in dub conference will know that in following Shaka’s distorted swirling dubonics and sheer physical weight, Coxsone will operate one piece of amp less and maintain a sharpness and a clarity, a kind of “round beat” and initially let the music do the work, before Poppa Festus – the Coxsone Hi-Fl controller– puts on the pressure, injecting tension into the rhythm and building the climax into the dub cuts. Playing reggae and presenting reggae are two different things, and to Coxsone playing a dance means more than catering for the militant steppers who mainline warrior rhythms. “We think of our dance public all the time. I am supposed to select music for the people to dance to, that is our job. That’s hat they’re paying us for. If I Lloyd Coxsone am playing as a disc, I like to have the majority of the people dancing. I have no other excuse than to make people enjoy themselves, and I can’t do that if I’m not fit to do my job.””We have to use our brains. You just can’t sling record onto the turntable, it have to be selected. Each rhythm coming after a next one have to be directed so that if you play a song with a certain argument you must find a next one with an argument to match the first.” Lloyd Coxsone’s reasoning and observations on sound are incisive and revealing and he is justifiably proud that “no other sound have achieved what Coxsone have done for reggae in the UK”. In its heyday of the 70s and 80s, with an endless supply of superior dubplates sourced from top producers in Jamaica, augmented by some of their own productions cut with high-ranking music makers in the UK, Sir Coxsone was undeniably top of Britain’s sound system circuit. Their superior selection and the manner in which they presented it to the public gave Coxsone the kind of credibility that most other sounds were never able to achieve thanks to the unbeatable tag-team of proprietor Lloydie Coxsone and his star selector, Festus, and an ever-changing crew of supporting members that kept the sound perpetually fresh and innovative.

“I brought that test pressing to England and start to play it, and it’s the first time people hear the name Burning Spear.” Lloyd Coxsone

The Sir Coxsone story really begins in Jamaica, where Lloydie and Festus knew each other as schoolkids, growing up in rural St Thomas to the east of Kingston, which has the reputation of being the ‘rebel parish,’ since the Morant Bay Rebellion and other notable uprisings took place there in slavery days. It is perhaps unsurprising that the parish later became a hotspot of soundsystem culture, given reggae’s general association with ‘rebel music’.“Growing up in St Thomas, there was a lot of sounds that inspire us, right in our region,” says Lloydie, his voice a slow, deep drawl. “Like there was Mighty Merritone, Atomic, Phonics, Mellow Canary. So when I come to England in 1962 to join my father and my brother, I didn’t really know that I was going to go down the sound system way, but it happened automatically. I know Festus from Jamaica, going to school, and when Festus come to England, we link and we create this history.”Both men were based in south London, amongst the growing Jamaican expat community. In fact, at his first London home, which was in Balham, Lloydie lived next door to a West Indian social club that had a resident sound called Queen of the West, Lloydie began playing on that sound until a friend introduced him to the better-paying Barry Skyrocket, based at Colliers Wood. Lloydie says he brought Festus to play on Skyrocket, not long after the latter’s arrival in Britain in April 1965, and by September of that year the pair had formed a set of their own called Lloyd the Matador, which soon became the hottest sound around. Incidentally, the name was lifted from the powerful set established by Lloyd Daley in Jamaica, which was standard practice for British sounds in those days, and the name made sense for the south London sound, too, since its chief proprietor also had Lloyd for his given first name.During the mid-50s, Duke Vin and Count Suckle introduced soundsystem culture to Britain, after stowing away on a banana boat at a time when rhythm and blues ruled Jamaica. These men and a number of counterparts played ska and rocksteady in basement shebeens and house parties through the mid-60s, with Suckle even bringing ska briefly into the West End before settling into a long residency in Paddington. But by the time the new reggae style hit Jamaica, down in south London, Lloyd the Matador transformed itself into Sir Coxsone sound, following a very contentious incident.

The disasters of the past become wisdom of the future and Coxsone shakes his head as he recalls how Lloyd the Matador blew up due to water in the amp. Being young and reckless, living for the moment and not dealing with saving and bank accounts, Coxsone was left no option but to return to deejaying a next man’s sound, as he had done originally with Barry Pierocket, reluctantly accepting an offer from the UK Duke Reid.

As Lloydie explains, “Matador had a big fight and mash up, so we weren’t playing no sound for two years. There was a sound in Balham called Duke Reid the Trojan, and some of my friends persuaded me to go and play Duke Reid. So I went as a selector and bring Duke Reid to become one of the biggest sounds in London. Neville the Enchanter was playing at a pub in Balham every Thursday and he left, so Duke Reid took the job and the sound went and string-up there every Thursday. One night I was coming late as the selector, and two white man grab me up at the door, and me and them have a fight, and I fling one of them down. I didn’t know that they were two police, so they gather all the police from the station and arrested me, and the policeman planted me with a big machete — I remember the policeman’s name up until today, his name is PC Salter.

“When I go to court in Balham High Road, Mr Reid was supposed to come and give evidence for me, because Mr Reid know I didn’t have any weapon, and Mr Reid only live round the road from the courthouse. The judge put off the case two times, and the third time I go round and beg Mr Reid to come, just walking distance, and he say, yes, he will come, but he didn’t. So the judge give me six months for the machete that the policeman planted me with. So while was I doing six months in Brixton Prison, I decide that I wouldn’t go back and play Mr Reid’s sound; I’m saying to meself, in Jamaica, you’ve got two big sounds, one named Duke Reid, and one named Sir Coxsone, so when I come out, I’m going to build over my sound and call it Sir Coxsone, and lick off Duke Reid’s head.”

“Coxsone sound started in 1968 in Clapham Common,” adds Festus. “Three of us start Coxsone sound: Lloydie, myself and [future Top Records label founder] Glen Marcinick, because Glen had two amplifiers, and we had the records. Then we start to play in the West End at the Grotto on Wardour Street, in front of the Flamingo jazz club.”

Coxsone later settled into a long residency at the Roaring 20s on Carnaby Street, bringing reggae firmly into the consciousness of a growing multiracial audience. Part of the appeal was the unknown exclusives that remained outside the grasp of any other soundsystem, including unreleased material by Bob Marley and the Wailers. “People used to come to the Roaring 20s just to hear ‘Rainbow Country’, because we were the only sound on the entire planet earth that got that song,” says Festus of the legendary number, recorded at Lee Perry’s Black Ark studio. “We played it for 21 years on dubplate till Mr Perry decided to release it!”

Burning Spear was another specialism of Sir Coxsone. In fact, the sound system was responsible for breaking Spear in Britain, at a time when he was not even well-known in Jamaica. The Spear link originates from the time when Lloydie Coxsone finally met the original Coxsone — that is, Studio One founder, Clement ‘Sir Coxsone’ Dodd, whom Lloydie was introduced to by veteran singer Alton Ellis, on one of his many visits to Jamaica in search of exclusive material. The pair hit it off, leading Dodd to sanction Lloydie’s use of the Coxsone name, and when Dodd asked Lloydie for feedback on a test pressing of an album he’d recently recorded with “a countryman,” it turned out to be the landmark Presenting Burning Spear LP. “I fall in love with a track on there named ‘Swell Headed’,” says Lloydie. “So I brought that test pressing to England and start to play it, and it’s the first time people hear the name Burning Spear.”

After Spear left Studio One to work with Jack Ruby, Sir Coxsone continued to air Burning Spear material before it was on general release, boosting the popularity of his peak-period works and enabling him to build a strong following in Britain. But it wasn’t just Burning Spear that the sound was associated with. Sir Coxsone was known for strong links with King Tubby, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Roy Cousins, Gussie Clarke, and a range of other producers in Jamaica.

In 1973, Lloydie began making his first forays into record production himself, but early efforts felt a bit random: there was a reggae instrumental of a Louis Jordan rhythm ‘n’ blues standard, cut with a London-based horn player, and a KC White record issued by Gussie in Jamaica, but crediting Lloydie Coxsone on its UK issue. Their exclusive I Roy dubplate ‘Coxsone Time’ was eventually issued by Roy Cousins in Britain too. But then, in 1974, Lloydie shook up the British reggae scene in an unprecedented fashion by cutting ‘Caught You In A Lie’ with teenage schoolgirl Louisa Mark, kick-starting the lover’s rock craze.

“When I produce music, I hardly want to release it, I just want to keep it, playing it on the sound,” Lloydie explains. “But, yeah, we made the first lover’s rock music with Louisa Mark that was recognised worldwide, coming out of England. And since that, it’s like we open a can of worms, where so many woman singers in England was inspired by this likkle 16-year-old girl. I think the other girls think that, if she can do it, we could do it too.”

“We started the revolution of everything.”

Lloyd Coxsone

Some sporadic Coxsone-produced roots reggae singles followed, with established figures like Delroy Wilson, Keith Poppin and Barry Brown, as well as a few with British-based vocalists such as Tony Washington and the J Sisters. The very rare 1977 album The Coxsone Affair had unknown dubs of Lloyd Campbell productions and some Channel One material, all embellished by unusual horn overdubs; later, King Of The Dub Rock featured scintillating dubs from Gussie Clark, as well as dubs of Lloydie’s own productions, while King Of The Dub Rock Part 2 was cut at Channel One and mixed by Scientist.

“We start go to Jamaica and start to record Fred Locks and Creation Steppers, and do Jimmy Lindsey’s ‘Easy’, and that’s where we really get into the producing thing,” continues Lloydie. “Mostly we was doing those things just for Coxsone sound, but we start to release them on the Tribesman label and that’s how we come into the business.”

Soundsystem culture is all about evolution and keeping abreast of the times. Sir Coxsone was one of the first British soundsystems to tour the UK, and as reggae’s audience widened, they began branching into other territories too, leading to the Outernational tag. “We started the revolution of everything,” Lloydie emphasizes, “cause there was some very good sound in London, like Metro Downbeat, Duke Vin, Count Suckle, Duke Lee, Sofrano B, but they were only great in London, they wasn’t going anywhere else. When me and Festus come with Sir Coxsone Outernational sound, we start to go to Bristol, Birmingham, Manchester, and we mash the whole of England. We are the first sound to play in Holland, the first sound go to France. Germany, Belgium. We revolutionise the reggae right through Europe and the US, and right here in the UK, and we hear a lot of people make claims that they do this, and they do everything, but we are the first soundsystem to play stereo, with weight, middle and top, and we are the first soundsystem to put two 18-inch speakers into a speaker box.”

Even though Sir Coxsone was at the forefront of the roots reggae scene, when the new dancehall style became the order of the day, Coxsone helped usher in that new wave as well, thanks largely to bringing through a younger crew. “Coxsone is a sound where, we always maintain a team,” Lloydie emphasizes. “When it come down into the 80s, we have youth like Blacka Dread, Gappy Crucial, Bikey Dread, and Levi Roots; they were the understudies to Festus and myself, and we tour so much places that we get a bit tired, so the sound automatically hand over to those youth, and they carry the sound into a different area.”

Soon, dancehall stars such as Frankie Paul, Super Cat and Nicodeemus were featured guest artists on the sound, and Blacka Dread launched into record production under the Sir Coxsone banner, cutting some of the best digital dancehall of the late 1980s. His passion for dancehall and his understanding of that field helped keep Sir Coxsone to navigate the scene’s turbulent waters. But by the dawning of the 90s, the sound was clearly beset by difficulties. “That is when Coxsone sound started to go down the hill,” Lloydie suggests. “After they put away the music that we had and start to cut their own thing, it couldn’t work, because the generation of people who listen to Coxsone over the years, the same standard was not there. So the crowd start to fall away. But we were a big team of people, and everybody was knowledgeable in their own right, so I don’t think we could have stayed together for ever. I go and do my own thing, Festus went and do his own thing, and the other man, them doing their own thing.”

Despite the long wilderness years, the enduring friendship of Lloydie and Festus means that another chapter of Sir Coxsone Outernational is about to unfold. A recent appearance backing Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry brought to mind their longstanding reputation, these two champions of sound thrilling the audience with a specially tailored selection as usual. “Although we split up, we always was friends,” Lloydie emphasizes. “It wasn’t in a bad way, so today we can get together. We reason and decide that we still have some history to give people who never really hear it. So no love was lost. We have got all the original dubplates and we are coming back now to let people hear some of the tunes that they never hear before. So we are back for real.”

Sir Coxsone’s 55th Anniversary Show “Uniting The Tribes Tour”

Friday 28th February 2020

8pm – LATE

SIR COXSONE OUTERNATIONAL ABA SHANTI-I MAD PROFESSOR SAXON KING TUBBYS LUV INJECTION (Birmingham) INDICA DUBS MAFIA & FLUXY SOUND LION PULSE (Bristol) FRONTLINE VINYL STAR S UPATONE I-SPY QUAKER CITY (Birmingham) JB CREW

Live PAs:

LEVI ROOTS LITTLE ROY WINSTON FRANCIS BROTHER CULTURE CHOSEN FEW BARRY ISAACS

Sir Coxsone Presents “Uniting The Tribes Tour” is a series of shows celebrating sound system culture to be held throughout the UK during February 2020. Each show will feature an impressive line-up of UK sound-systems led by the legendary Sir Coxsone, who recently marked his 55th anniversary as one of the world’s leading reggae soundmen. Other well-known names already confirmed include Mad

Professor, Aba Shanti, King Tubby’s in addition to a growing line-up of singers and deejays.

Interest in reggae sound systems is currently at an all-time high, and there’s a younger generation of reggae lovers from across the world building their own amps and speakers, cutting dubplates and starting record labels in greater numbers than ever before. The MCs and “live” mixes that were synonymous with reggae soundsystems of the past have returned, and there’s now a wealth of festivals, films, exhibitions, books, online communities and academic studies representing all aspects of sound system culture. It’s had a massive influence on genres such as hiphop, drum & bass, UK dub, and grime, and also left an indelible stamp on fashion, language and a range of other lifestyle choices.

The sound of young Jamaica first came to the UK after WW2. Early sound systems helped provide a sense of belonging and purpose, as well as a platform for aspiring entrepreneurs, technicians, carpenters and performers.

“We had the best set of sound-systems here and the most reggae music, even more than in Jamaica,” says Lloyd Coxsone. “We are the ones who establish it and then expose it worldwide. And we bring a spirit to other people because the sound-system is a joyful thing really. We want to see people smiling and looking happy, y ‘know?” He and other well-established sounds like Channel One are keepers of the flame. There’s history and cultural resonance in every note they play, and years of unwritten tradition in their approach. They’ve learned their craft the hard way, and bring all of that knowledge to bear when stood behind the decks entertaining a crowd. These Uniting The Tribes events are intended to convey the thrills and experience of witnessing authentic UK reggae sound-system culture first-hand, in venues across the UK both small and large and to unite all the soundmen on one tour which will spread their message of unity and belonging.[:]