Kenneth Lloyd Khouri, Graeme Goodall, Stanley Motta, Linford Anderson, Sylvan Morris

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ken_Khouri

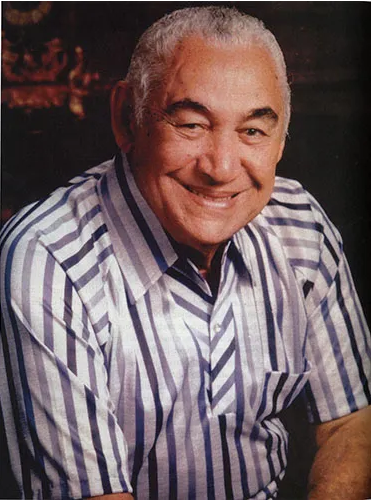

Kenneth Lloyd Khouri

Born 1917 in Kingston/Jamaica in a Lebanese/Cuban family.

Ken Khouri was a furniture salesman before he became a Jamaican music industry pioneer after he bought recording equipment in Miami in the 1940’s. Lacking a studio, Khouri traveled through clubs and recorded Calypso music, and then sent the master to the UK to get pressed, since there was no record manufacturing in Jamaica at the time.

In 1947 he built up a studio (Records Limited) which would become Federal Records Studio, which was for a long time the only recording facility in Jamaica.

In the early 1950s he finally bought a pressing plant in California, being the first man in Jamaica to press records.

On his two labels, Times Music and Federal Records (3) , Khouri released Boogie, RnB and Calypso records; also he had Jamaica distribution contract with Mercury Records. Later, when Ska and Rocksteady set in, he recorded the genre’s greats like Prince Buster and Hopeton Lewis. He was also the owner of KK Mastering Labs, Inc. which was first located in Jamaica before relocating to Miami, FL.

In 1981, Ken Khouri sold his studio and pressing plant to Bob Marley’s Tuff Gong record label. Khouri died on 20th September 2003 in Kingston

His second-born son Paul Khouri is a producer and mastering engineer based in Florida.

Federal Records is a cornerstone in the history of the Jamaican music industry.

It was the island’s first domestic recording studio and where the pioneers of reggae, such as Sir Clement ‘Coxsone’ Dodd, Duke Reid and Prince Buster, recorded the earliest examples of popular Jamaican music.

The name of the studio’s founder, Ken Khouri, is not well known

outside of Jamaica, but his contribution to Jamaican music is immeasurable and he is a well-respected figure in his homeland. He left behind many important recordings that should be passed down from generation to generation.

https://www.ipsnews.net/2003/09/arts-weekly-music-producer-pioneered-reggae-forerunner-rocksteady/

Khouri Producer Pioneered Reggae Forerunner, ‘Rocksteady’

Howard Campbell

KINGSTON, Sep 30 2003 (IPS) – When Jamaican record producer Kenneth Khouri died of heart failure here Sep. 20, aged 86, there was little mention of his passing in the local media. Indeed, it was three days later that his death was first reported. In life, the unassuming Khouri always kept a low profile.

Though he was one of the first record industry moguls in the Caribbean, his legacy is largely understated; he may not have had the huge catalogue of hit songs of other early reggae producers, such as Chris Blackwell at Island Records and Clement Dodd at Studio One, but for over 20 years Khouri’s Federal Records was the epicentre of Jamaica’s music business.

That is where Bob Marley recorded his first song, ‘Judge Not’, in 1962. Paul Simon recorded part of his 1972 album, ‘Mother And Child Reunion’ there, while The Rolling Stones visited in 1972 to do sessions for their 1973 album, ‘Goat Head Soup’.

Federal was also the Caribbean distributor for major U.S. record companies such as Decca, Capitol and Columbia Records.

Ironically, Khouri’s work as a pioneer was being recognised in the months leading to his death. In August, he was honoured at the annual Tributes To The Greats ceremony in Kingston, and in September, the Institute of Jamaica historical society named him and Blackwell among the 12 recipients of its Musgrave Medal. The medal, one of Jamaica’s most respected civic awards, will be handed out here Oct. 8.

Paul Khouri, one of Ken Khouri’s six children, says his father and Federal Records never got the respect they deserved from Jamaicans. “People have this notion that Bob Marley started reggae – we created rocksteady and formulated reggae,” he said in a 2002 interview.

Reggae historians credit the Khouris for starting the rocksteady craze of the mid and late 1960s. The slower, bassier beat replaced the jazz-based Ska as the sound of choice among partygoers here when singer Hopeton Lewis cut ‘Take It Easy’ in 1965 at the Federal studio.

Four years later, as the sound of Jamaican popular music again evolved, singer-songwriter Bob Andy recorded a version of American singer Joe South’s ‘Games People Play’ at Federal. Paul Khouri insists it is the first reggae song; most musicologists cite Larry Marshall’s ‘Nanny Goat’ in 1968 as the song that got the reggae train rolling.

While Paul Khouri’s claims may be debatable, no one can question the magnitude of his father’s contribution to the development of Jamaica’s pop music.

Ken Khouri was born in 1917 in rural St. Mary parish to a Lebanese father and Jamaican mother. He was working as a manager in the in-bond sector when he bought a disc-recorder from his mechanic and started manufacturing records by Jamaican calypsonians Lord Flea and Lord Fly.

Sales by both performers were so good that Khouri left his job and went full-time into the record business, which was accelerating during the mid 1950s. He started Federal Records in September 1954 and seven years later established the Federal Studios, where Jamaica’s leading producers eventually recorded.

As Jamaican music began making ripples overseas in the late 1960s and 1970s, U.S. acts began visiting Kingston to soak up the island’s increasingly popular beat.

Most of them went to Federal, including singer Johnny Nash, who recorded many of his reggae-tinged songs there. The record studio scenes in the 1972 film classic, ‘The Harder They Come’, were also shot at Federal.

For most of the 1970s, reggae was dominated by Rastafarian singers and protest records. Because Federal’s management was from Jamaica’s middle-class, the Khouris stayed away from such heady sounds; instead, Federal released light-hearted, up-tempo numbers by singers like Ernie Smith (‘Duppy Gunman’) and Pluto Shervington (‘That Thing There’).

In 1974, the company picked up distribution rights for Ken Boothe’s cover of U.S. pop band Bread’s hit song, ‘Everything I Own’. Boothe’s reggae version was a smash in the United Kingdom, where it made the top 20 of the national charts.

But by the end of the decade, recording all but ceased at Federal, which seemed out of touch with the political climate.

Like many in Jamaica’s middle-class, the Khouris moved to North America, fearing that the socialist government of Prime Minister Michael Manley was moving towards Communism. When Manley was beaten at the polls in October 1980, Ken Khouri returned but left the music business for good in 1981 when he sold Federal Records.

He lived in virtual seclusion until his death, splitting his time between Jamaica and Miami, where the family operates K&K Records, which distributes records from the Federal catalogue.

https://www.ndntk.it/2020/03/25/graeme-goodall/

GRAEME GOODALL.

IL DOCTOR BIRD ALLE ORIGINI DEL SUONO GIAMAICANO

25 Marzo 2020

A cura di Al Groove

Graeme Goodall fu un ingegnere del suono figura chiave dei primi giorni dell’industria musicale jamaicana. Ai più conosciuto come “Doctor Bird” fu anche co fondatore dell’etichetta Island e costruttore della maggior parte della musica prodotta nell’isola.

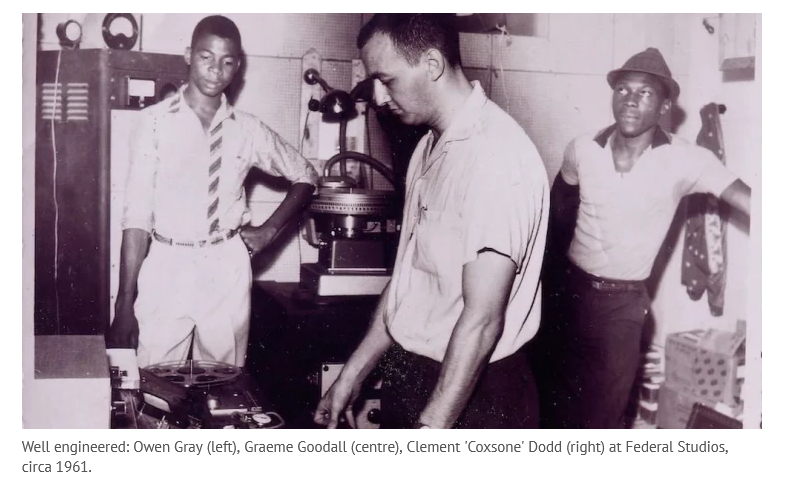

Iniziò come dj radiofonico per arrivare a costruire i due templi della musica jamaicana: i Federal Studios negli anni ‘50 ed il Jamaican Recording Studio (Studio One) nel 1963 avviando al mestiere i primi tecnici del suono.

Nato nel 1932, è cresciuto in Australia a Caulfield, Victoria, ha studiato alla Caulfield North Central School e allo Scotch College. All’inizio degli anni ’50 ha lavorato brevemente presso la stazione radio di Melbourne 3UZ prima di studiare televisione a Londra e allenarsi come ingegnere presso la International Broadcasting Company. Fu coinvolto nell’industria discografica indipendente e viaggiò in Giamaica nel 1954 per creare la prima rete radio FM a Kingston – Radio Jamaica Rediffusion.

Ha continuato a lavorare come ingegnere capo della Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation ed ha iniziato a registrare musicisti locali presso gli studi Radio Jamaica. Ha contribuito inoltre a costruire il primo studio di registrazione dedicato della Giamaica (Federal Records, ricostruito nel 1961 e in seguito diventato Tuff Gong Recording Studio) con l’imprenditore locale Ken Khouri, nella parte posteriore del negozio di mobili Khouri in King Street.

Goodall ha lavorato come ingegnere di registrazione per Ken Khouri in alcune delle prime registrazioni in studio giamaicano. Lo studio non solo ha fornito la prima struttura di registrazione dell’isola, ma ha anche prodotto dischi in acetato, consentendo agli operatori di sound system di registrare tracce e renderle disponibili per la riproduzione in poche ore.

Conosciuto dai musicisti locali come “Mr. Goody“, Goddall ha continuato a collaborare alla costruzione di numerosi studi, tra cui Dynamic Sound, Studio One e successivamente Channel One Studios, e ha svolto attività di ingegneria per produttori come Clement “Coxsone” Dodd , Byron Lee e Leslie Kong, registrando Laurel Aitken (“Boogie in My Bones”) Millie (“My Boy Lollipop”), The Wailers, Prince Buster, The Skatalites, Derrick Morgan e Desmond Dekker, tra molti altri. Ha anche formato ingegneri giamaicani come Sylvan Morris e Lynford Anderson.

Nel 1959 ha co-fondato Island Records con Chris Blackwell e Leslie Kong, ma il suo rapporto con Blackwell si è interrotto. Nonostante ciò ha continuato a fondare sue etichette dopo essersi trasferito nel Regno Unito nel 1965, le più riuscite furono Doctor Bird e Pyramid.

Dopo che “Poor Me, Israelites” di Desmond Dekker si dimostrò popolare nei club ma senza ottenere molti airplay a causa della produzione, Goodall fece in modo che Kong gli inviasse i nastri principali; lo remixò e lo pubblicò nel Regno Unito nel 1969 su Pyramid come “Israelites“, il singolo andò in cima alla classifica delle hit nel Regno Unito e vendette oltre due milioni di copie

Mr Goody ha anche gestito la West Indies Records, e contribuito a creare Trojan Records e Attack Records.

Goodall sposò la giamaicana Fay nel 1961 e nei primi anni ’70 si trasferirono negli Stati Uniti dove morì nella sua casa di Atlanta, in Georgia, il 3 dicembre 2014 per cause naturali, all’età di 82 anni.

Una figura oscura, ma sicuramente importante per tutta la Giamaica e il suono che proviene dall’isola.

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/graeme-goodall-audio-engineer-who-became-a-crucial-figure-in-reggae-and-helped-establish-island-records-10078685.html

Graeme Goodall, an Australian from Melbourne, was one of the hidden heroes of Jamaican music. “He was a wonderful guy, full of energy, and very bright, very smart. A terrific and exceptional person,” said Chris Blackwell, with whom Goodall helped establish Island Records.

“Goody”, as he was known, was involved in the technical setting-up of Jamaica’s first two radio stations; he was audio engineer on all Island Records early Jamaican releases, including Laurel Aitken’s “Boogie In My Bones”, the label’s first hit; he built the studio, set up the pressing plant and was a partner in Kingston’s earliest record company, Federal; in the UK he set up the Dr Bird and Pyramid labels, releasing classic songs, including Desmond Dekker’s “007 (Shanty Town)”, a UK hit, and “Israelites”, the first Jamaican record to make the US top 10.

Following a visit in 1962 to a Downbeat sound system event in dusty Trenchtown run by the legendary Coxsone Dodd, Goody understood the importance of the bass sound in Jamaican music: his pregnant wife Fay felt their unborn child shifting in her belly to the bass reverberations growling out of the speakers. From then on he always emphasised the bass in recordings in which he was involved.

In Melbourne Goodall had worked in radio, helping set up the outside broadcast of Queen Elizabeth’s 1954 visit to the city. He moved to London that year, aged 22. His experience in both live work and commercial radio – unknown in the UK – secured him work with IBC, a production company who made such quiz shows for Radio Luxembourg as Strike It Rich and Shilling a Second. IBC’s studio also produced records, and Goodall worked with up-and-coming artists like Petula Clark.

In 1955 he went to Jamaica to help start up a local commercial radio station. For RJR – which had personalities like Charlie Babcock, “the cool fool with the live jive” – he set up the entire technical network, the first FM station in the British Commonwealth. Discovering a pay gap, a source of resentment, between local workers and overseas “experts”, Goody consciously made friends with working-class Jamaicans, spending time at the docks learning patois, earning a reputation as a man of the people.

Returning to Melbourne after three years, Goody was quickly called back to Jamaica: his technical expertise was required by the Jamaican Broadcasting Corporation, JBC, a state-owned channel which began broadcasting in June 1959.

Almost as soon as he returned Goody, Chris Blackwell and Leslie Kong, an ice-cream entrepreneur, set up Island Records. Laurel Aitken’s “Boogie In My Bones”, a local No 1, was recorded in the early hours at RJR’s concert studio, employing the Caribs, a musical group which consisted entirely of Australians. “We’d been brought over from Surfer’s Paradise to play in Kingston’s Glass Bucket Club,” recalled Peter Stoddard, their keyboard player. “Graeme would come in and get the balances and off we went. We played on all the early Island recordings, all done at RJR.”

Goody worked with other producers, again using RJR’s studio. For Edward Seaga, later Jamaica’s Prime Minister, he made “Oh Manny Oh” by Higgs and Wilson, the first local hit to sell 50,000 copies.

After setting up Federal recording studio with his friend Ken Khouri in 1961, Goody became its chief engineer. As it was Jamaica’s only professional recording operation, Goody worked with every significant Jamaican artist of the era, including the Wailers, the Skatalites and Jimmy Cliff. The producers Duke Reid, Coxsone Dodd and Prince Buster also made their early releases at Federal, and Goody forged relationships with them.

He also taught future prominent engineers such as Sylvan Morris, revered for his work for Dodd’s Studio One label. Moving to London in 1962 with Blackwell, by 1965 Goody had stepped aside from Island.

Setting up the Dr Bird label, and then, in partnership with Leslie Kong, Pyramid, on which Desmond Dekker’s hits appeared, Goody utilised his Kingston street connections, calling on the likes of Lee “Scratch” Perry, Bunny Lee, Harry J, and Joe Gibbs for their latest productions.

By the early 1970s both Dr Bird and Pyramid had ceased to trade. Goodall spent most of his time in Jamaica; later in the decade he set up the Tuff Gong studio for Bob Marley. Moving to Miami, then Nashville, and finally Atlanta, Goody set up a business maintaining recording equipment and consoles.

“What was so strange,” said Chris Blackwell, “was that I desperately felt an urge to speak to him a couple of days ago and managed to track him down: he said he was feeling a lot better. And then he was gone that evening. Really weird. Goody was a really important man, and a great one at that.”

Graeme Goodall, audio engineer: born Melbourne 1932; married 1961 Fay Wong (two children); died Atlanta, Georgia 3 December 2014.

https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2014/12/graeme-goodall-rip

By David Katz on December 8, 2014

Graeme Goodall was an extremely important figure in the development of reggae. Something of an unsung hero, Mr Goody, as he was affectionately known, was responsible for engineering most of the earliest recordings issued on vinyl in Jamaica, during the late 1950s and early 1960s. He also helped build some of the most noteworthy Jamaican recording studios, was one of the original founders of Island Records, and played an important role in helping reggae to gain a foothold in Britain, most notably via the Pyramid and Doctor Bird labels he established in London during the mid-’60s.

Goodall was born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1932. After leaving school, he worked for commercial AM radio stations, performing a variety of audio engineering functions, including work on remote music broadcasts. In 1954, Goodall travelled to London, ostensibly to further his education in television engineering, and after selling appliances for a time to make ends meet, he trained as an audio engineer at the International Broadcasting Company (IBC), then the largest independent recording studio in Britain, voicing pop stars like Petula Clark at the facility and doing remote recordings around the country of quiz programmes.

Redifussion then offered him the chance to help install their cable radio subscription service in Nigeria or Jamaica, and after taking advice from an elder cousin, Goodall went to Jamaica on a three-year contract, designing and installing the first commercial FM service in the British Commonwealth as Radio Jamaica Rediffusion (RJR), using a studio transmitter link to reach various Jamaican locations during a time when FM transmitters were unavailable. During this initial Kingston sojourn, Goodall soon became involved in Jamaica’s fledgling music industry, helping his friend, Ken Khouri, to install basic recording equipment at the back of his furniture store on King Street in 1955 to form Records Limited, where some of the earliest mento recordings were made. Goodall also oversaw a recording of the Jamaican military band at RJR for Stanley Motta, since Motta’s tiny Harbour Street studio was too small to accommodate all its members.

At the end of his Rediffusion contract, Goodall returned to Melbourne to begin working for a local television station, but within six months, the Jamaican government requested he return to the island to help establish the Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation (JBC). Once back in Jamaica, Goodall soon became more concretely involved in the music scene, most notably arranging for Chris Blackwell to record Laurel Aitken’s landmark hit “Boogie In My Bones” at RJR in 1959, with musical backing provided by the Caribs, an expatriate Australian club act that featured Goodall’s future brother-in-law, Dennis Sindrey, on guitar.

Goodall subsequently engineered Blackwell’s further productions with Aitken, Owen Grey and Wilfred “Jackie” Edwards, becoming a partner in Blackwell’s Island Records along with Chinese-Jamaican producer, Leslie Kong, with whom he developed an enduring friendship. Other semi-clandestine after-hours sessions were cut at RJR for Edward Seaga, including Higgs and Wilson’s influential “Manny Oh,” and “Dumplins,” the debut single by Byron Lee and the Dragonaires, though Seaga would shortly abandon the music business for a political career. Nevertheless, these seminal recordings proved that a Jamaican music industry was a viable concern, and material recorded with local artists dramatically increased, following Goodall’s initial impetus.

In 1961, momentous things happened for Graeme Goodall: he married Fay Wong, a Chinese-Jamaican that worked as ground staff for BWIA in Kingston, and he also became the chief engineer at Ken Khouri’s Federal recording studio, then the sole professional recording facility in Jamaica. Goodall was thus responsible for pivotal recordings by every important recording artist of the ska era, including the Skatalites, Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff, Count Ossie, Rico Rodriguez, Higgs and Wilson, Theophilus Beckford, Derrick Harriott, Stranger Cole and Millie Small, to name but a few. He worked closely with all the leading producers of the day, forming strong working relationships with Clement “Sir Coxsone” Dodd, who would later found Studio One, and his main rival, Duke Reid, who would open Treasure Isle recording studio in the mid-’60s. Prince Buster made all but one of his early recordings as an independent producer at the facility, where he also developed a lasting friendship with Goodall; Lloyd “The Matador” Daley and Harry Mudie were among many others to benefit from Goodall’s guidance.

In these early years, Goodall facilitated many practices that greatly shaped the evolution of Jamaican popular music; after attending a Sir Coxsone sound system dance, Goodall understood the primacy of the bass in sound system culture, which changed his approach to sound recording at Federal. He also recorded Jamaica’s first stereophonic record there, which took the form of Byron Lee’s Caribbean Joy Ride, issued by Federal in 1964. During the same era, Goodall built the West Indies Records Limited studio (AKA WIRL) for George Benson and Clifford Rae – the first version of the studio later known as Dynamic Sounds. He was also instrumental in training the next generation of sound engineers, schooling both Sylvan Morris, who would become chief engineer at Studio One (and later, Harry J and Dynamic Sound), and Byron Smith, who would be head engineer at Treasure Isle, as well as technical engineer Bill Garnett, who worked at Federal, Dynamics, and Randy’s. It is clear that each of these engineers greatly benefitted from Goodall’s tutelage, helping to ensure the Jamaican music scene was committed to sonic innovation, rather than timid imitation.

Once Jamaica achieved its independence from Britain in August 1962, Goodall helped Chris Blackwell shift Island’s headquarters to London, and helped arrange for Mille Small to record the monster ska-pop hit, “My Boy Lollipop,” there. However, he soon became dissatisfied with the way the Island partnership was evolving, feeling side-lined by the A&R staff Blackwell employed. He thus formed the Doctor Bird label in partnership with George Benson and Clifford Rae in 1965.

Making use of his strong links with established producers such as Clement Dodd, Duke Reid, Lloyd Daley and Byron Lee, Goodall also cultivated his relationships with the younger guard of ghetto promoters that were then rising in the Kingston music ranks, including Carl “Sir JJ” Johnson, Bunny Lee, Joe Gibbs, Harry J, Lee “Scratch” Perry, and Rupie Edwards; Doctor Bird also handled a few British reggae recordings, produced in London by the likes of Sugar Simone, the Cimarrons and the Seven Letters, typically recording at a studio Goodall operated in Fulham Road. Since Goodall had impeccable taste and exceptional Kingston connections, the label housed a range of noteworthy material, from the rousing ska of Roland Alphonso’s “Phoenix City,” the Gaylads’ racy “Lady with the Red Dress,” and Justin Hinds’ proverbial “Higher the Monkey Climbs,” to some defining moments of the rock steady era, such as Alton Ellis’ landmark “I Have Got a Date,” the Latinesque original take of the Maytals’ “Bam Bam,” plus Bob Marley and the Wailers’ defiant “Good Good Rudie.” There were some early reggae scorchers too, such as Bob Andy’s spirited and oft-covered “Sunshine for Me,” as well as numerous influential hits by the Ethiopians, including “Engine 54,” “Everything Crash” and “Hong Kong Flu.”

At the same time, a new partnership with Leslie Kong yielded the Pyramid label, which found near-overnight success with the unprecedented popularity of Desmond Dekker’s “007 (Shanty Town),” which was later dwarfed by the incredible success of his “Poor Mi Isrealites.” Genre-defining early reggae tracks by the Maytals surfaced on Pyramid too, including “Do The Reggay,” “Sweet and Dandy” and “Pressure Drop,” and there was fine work by Derrick Morgan and Roland Alphonso. However, his gospel imprint, Master’s Time, which handled secular work produced by Duke Reid and Sonia Pottinger, failed to achieve any significant success.

Although Goodall enjoyed a massive hit with Symarip’s “Skinhead Moonstomp,” which surfaced on Trojan’s Treasure Isle subsidiary in 1969, both Doctor Bird and Pyramid folded at the start of the 1970s, though the latter was revived in 1973-4, for a handful of roots reggae releases. Goodall continued to spend the bulk of his time in Jamaica, bringing Jack Price to the island in 1971 while helping him to form Sioux Records, and going on to work on a variety of albums at Dynamic Sound, even mastering King Tubby’s excellent Dub from the Roots album there.

After working in Jamaica, off and on, to the end of the 1970s, Goodall subsequently settled in Miami, where he worked for Sony, selling and maintaining recording consoles and professional tape machines. He later served a similar function for the company in Nashville, and ultimately in Atlanta, where he remained after his retirement.

Though Graeme Goodall’s impact on reggae has sometimes been unfairly overlooked, his incredible contribution is undeniably of lasting importance. He is survived by Fay and their two children.

https://bigmikeydread.wordpress.com/2010/08/25/stanley-motta-mottas-recording-studio-kingston-mrs/

Stanley Motta – Motta’s Recording Studio Kingston

August 25, 2010

Being a short study of one producer and label from Kingston.

Stanley Motta was a businessman living in Kingston Jamaica who originally traded in electrical goods and began his recording ‘studio’ in the early 1950s, before there were any other studios or mastering and pressing facilities on the Island. He would have artists record their songs in one shot and the acetates would then be sent for duplication in the United Kingdom. These records were then sent back to Jamaica to be bought mainly by early tourist visitors to the Island. Motta recorded Mento; a style of music that is sometimes inaccurately described as Jamaican Calypso. To this day Stanley Motta Cellular Repair is a Jamaican company, specialising in electrical repair.

First ever Jamaican production to get UK release.

In 1952 Melodisc the UK label reknowned for it’s ‘Ethnic’ output produced MELODISC Cat no – 1214 / MOT 01-8. This is the first Jamaican produced single to see a release in the UK. Having been written and recorded and ‘produced’ in Jamaica the acetates were sent to the UK and pressed both for release in the UK and Jamaica, both issues of the single share exactly the same Matrices. This intimates that they were pressed by the same company, but labelled with two different record company labels. MRS (Motta’s Recording Studios) and Melodisc.

The Home Market

Initially local interest was limited, the up-market Kingstonians were not interested in what they saw as the ‘Rural’ music of Jamaica and it wasn’t until the western white tourist audience grew that Jamaicans themselves, at least the wealthier ones, began to take an interest. Poorer Jamaican families could rarely afford the equipment to play the 78rpm records on and so it was left to them to write and perform the songs that Stanley Motta recorded.

Mento is now a sought after collectors commodity, rare and VERY difficult to find. Once it was just something that captured a little of the flavour of a visit to the Caribbean and something to put away in the attic with the Hawaiian shirt, holiday snaps and Bermudan shorts.

Later in his career Motta had a few now rare 45rpm singles and E.P.s pressed and also released his music on a well known series of 10″ Lps, amongst them the ‘Authentic Jamaican Calypsos’ Series with vols 1 to 4. Some of the material released on these 10″ Lps was also released by the London label as ‘Authentic Jamaican Calypsos’ this time without a series number and a as a compilation of tunes that appear on the Jamaican produced series of the same name. In England at least this London Lp is easier to find.

Rare MRS E.P. of Count Lasher and the less desirable Brute Force Steel Band

Mento continues to be more easily found in the United States where the short hop from Miami had meant that tourists from North America were more likely to visit than other nationals. Of course the Brisith colonialists only left Jamaica in 1962, however it remains hard to find Mento in Britain for some reason.

You can find out more at the excellent – http://www.mentomusic.com/

https://skabook.com/2014/01/03/stanley-motta-recording-pioneer/

Stanley Motta, Recording Pioneer

January 3, 2014

Stanley Motta is always mentioned as an early pioneer in the ska industry since he had the first recording studio on the island, although they were not pressed there–Motta sent the acetates to the U.K. for duplication. But Motta began the recording industry in Jamaica. His recording studio was opened in 1951 on Hanover Street and his label, M.R.S. (Motta’s Recording Studio), recorded mostly calypso and mento. Motta’s first recorded in 1952 with Lord Fly whose birth name was Rupert Lyon. It is to be noted that in his band on these recordings were Bertie King on clarinet, an Alpha Boys School alumnus who would go on to have a successful jazz career in Europe, as well as Mapletoft Poule who had a big band that employed many early ska musicians and Alpha alumni. Motta also recorded artists like Count Lasher, Monty Reynolds, Eddie Brown, Alerth Bedasse, Jellicoe Barker, Lord Composer, Lord Lebby, Lord Messam, Lord Power, and Lord Melody (good Lord!).

There is a strong ska connection too. While I originally thought and posted that Baba Motta was Stanley Motta’s little brother and got that misinformation from Brian Keyo (here: http://www.soulvendors.com/rolandalphonso.html), I have been corrected by mento scholar Daniel Neely, as you will see from his fantastic and helpful comments below. They, in fact, are not related. Baba Motta was a pianist and trumpeter who also played bongos at times. Roland Alphonso performed with Baba Motta and Stanley then employed Roland to play as a studio musician for many of his calypsonians. Baba Motta had his own orchestra based at the Myrtle Bank Hotel. Baba Motta also recorded for his brother Stanley Motta with Ernest Ranglin. And other ska artists who recorded for Stanley Motta include Laurel Aitken and Lord Tanamo. Rico Rodriguez also says he recorded for Stanley Motta. Theophilus Beckford also performed for other calypsonians that Motta recorded, playing piano before he cut his vital tune “Easy Snapping” for Coxsone, the first recognized ska recording.

So who was this Stanley Motta character and what was his interest in Jamaican music? Well as most Jamaican residents know, Motta was the owner of his eponymous business that sold electronics, camera equipment, recording equipment, and appliances. They also processed film, if you remember that! Motta started his business in 1932 with just two employees. Motta’s grew to hundreds of employees over the years and they sold products from Radio Shack, Poloroid, Hoover, Nokia, and Nintendo, to name a few. Stanley Motta was born in Kingston on October 5, 1915. He was educated at Munro College and St. George’s College. He was married twice and has four sons, Brian, David, Philip, and Robert.

Motta chose to get into recording perhaps because it was a new industry for the island. And as a businessman, he saw that there were tourists who flocked to Jamaica with spending money, and in an effort to capture some of that money, he began recording to send them home with a souvenir. Many of these calypso and mento recordings for MRS were intended to be souvenirs, a take home example of the sounds enjoyed while on the north coast beaches. In fact, later Motta would serve on the board of the Jamaica Tourist Board from 1955 to 1962, so this was a focus for Motta. He recorded 78s, 45s, but also 10 full-length LPs including “Authentic Jamaican Calypsos,” a four volume series targeted at tourists upon which Roland Alphonso is a featured soloist on the song “Reincarnation.” In short, Motta was an entrepreneur, so his interest in recording came from a vision to fill a need, and he quickly moved on into more enterprising endeavors when he saw that need was being met better by others, like Federal Records, a physical pressing plant, and he chose to focus on his retail stores instead, stores which are still in business today.

Motta was also involved in broadcast, but not as you might think. In 1941, after viewing a program that was broadcast on NBC, Motta was so moved by the content of the program titled “Highlights of 1941,” that he wrote to NBC to obtain a recording of this broadcast. He secured the one-hour program which he then showed for audiences at the Glass Bucket Club and he used donations from the screening to support war funds. The program dramatized many of the events of the year interspersed with real footage of Pearl Harbor and the milestones leading up to World War II.

Motta was likely also a supplier for many sound system operators, as you can see from the advertisement above. He sold amplifiers, speakers, and all types of recording equipment so without his influence, the face of Jamaican music would not be the same, in many ways. Share your stories, memories, and research on Stanley Motta here and keep the dialogue going!

Here are a number of links to more information on Stanley Motta and his recording legacy:

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1842828

http://www.mentomusic.com/1scans.htm

http://bigmikeydread.wordpress.com/2010/08/25/stanley-motta-mottas-recording-studio-kingston-mrs/

Perhaps motivated by a desire to have recordings of local music to sell in his namesake department stores, Stanley Motta’s MRS (Motta’s Recording Studio) label released at least 70 tracks in the country and dance band styles by a variety of excellent artists on more than fifty 78 RPM singles , a few 45 . Mostly drawing from these, MRS released a five volume series of 10″ LPs, called, “MRS – Authentic Jamaican Calypsos”, as well as at least three other LPs and at least one “album” of 78 RPM singles.

MRS is the first mento label and the start of Jamaican’s recording industry. Descriptions of these albums start below, beginning with the MRS “Authentic Jamaican Calypsos” series. This is followed by some additional narrative on Motta and his label as well as several 1950s advertisements from The Daily Gleaner for the record department of Stanley Motta’s stores.

A nice collection with Lord Messam’s great rural mento on the first side and Baba Motta’s smooth urban sounds on the other. (See the Lord Messam page for a discussion of the Messam tracks.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynford_Anderson

Linford Anderson

Anderson was born in Clarendon Parish, Jamaica on July 8, 1941, and gained his early studio experience working for the RJR radio station, after initially being employed there as a log keeper, having studied accountancy.[From there he moved on to Ronnie Nasrullah’s recently created WIRL studio, where he gained experience with a two-track mixer, under the guidance of Australian engineer Graeme Goodall.[ His engineering skills were used extensively by producer Leslie Kong, and he eventually moved into production himself, using an Ampex two-track mixing board to create remixes of tracks and to combine several tracks into a single song. He also founded the Upset record label in 1967 along with Lee “Scratch” Perry and trainee engineer Barrington Lambert.His self-productions included “Pop a Top”, which he described as the first ever Jamaican “talking” record (although a handful of deejay records had been released earlier), which at the time of its release in early 1968 was unusual in that its rhythm was noticeably faster than the prevailing rocksteady beat. “Pop a Top”‘s rhythm track was based on Dave Bartholomew‘s “South Parkway Mambo”, and its lyric was based on a Canada Dry commercial; The song was later used by Canada Dry in an advertising campaign in the 1970s.The line “taste the tits, taste the tits” caused controversy when it was played by John Peel on his BBC Radio 1 show, with the BBC receiving a number of complaints. He further contributed to the development of reggae later in 1968 when he worked with Perry on “People Funny Boy”, which had a rhythm based on music that Anderson and Perry had heard at a Pocomania church service the night before.

Anderson has been described as one of the most gifted recording engineers ever to work in Jamaica and was described by Winston Holness as “the greatest engineer at those times…a genius in the business”.He worked for several years for Byron Lee at his Dynamic Sounds studio, working on recordings including the backing track to Roberta Flack‘s “Killing Me Softly with His Song“, and on recordings by The Wailers. He stated in the 1990s that during that period he would record or master up to 100 songs a day.He also recorded for Lee himself, including the 1970 single “The Law”.In 1970, Anderson mixed the first truly multitrack dubs at Dynamic Sounds.He also co-produced the Byron Lee & the Dragonaires album Reggay Blast Off the same year.

In 1977, Anderson emigrated to New York City, where he eventually landed a position as an audio engineer for the United Nations. He retired to Charlotte, North Carolina in 2004. After suffering a lengthy illness, Anderson died on March 16, 2020.

Linford Anderson was born on July 08, 1941 in Clarendon, Jamaica. Andy Capp, as he was affectionately called by many, grew up in Kingston Jamaica, graduating from Buxton High School in 1959. Andy had an early chance introduction to the Radio, Television, and Recording industry in 1961 when a total stranger encouraged him to apply for a position at the local radio station, Radio Jamaica Reddifusion (RJR). He was hired as a log keeper and was responsible for recording the commercials played and the order in which they were being played. His good fortune continued when a second position presented at RJR for an Audio Engineer. Andy applied and was able to complete a required three month training course in less than three weeks.

Andy’s talent was immediately recognized as he went on to receive five Production Awards at RJR for Special Radio Programs over a three year span (1961-1963). His radio broadcasting career at RJR was interrupted by his desire to venture into music recording. Andy’s transition to recording studio engineering was aided by Byron Lee of the Dragonaire’s Group. Byron Lee hired Andy as his Chief Recording Engineer at West Indies Records Label in 1963. Andy was instrumental in creating the new Rock Steady and Ska sounds that emanated from Jamaica during those years from 1963 through 1970. Andy went on to record accomplished artists to include Bob Marley, Eric Clapton, Roberta Flack, Jimmy Cliff, Peter Tosh, Derrick Harriott, and Prince Buster, to name a few. He received special recognition for his work recording Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly” in 1966 while honing his craft at Dynamic Sounds Recording Studio.

His passion for recording evolved into some playful and creative experimentation that led to the recording of several songs of his own, to include “Pop A Top” and “The Law.” Andy’s studio recording ended in 1971 when he returned to RJR to serve as their Chief Broadcast Engineer for the next six years. Andy migrated to the United States in 1977 and lived in Bronx, New York. He drove a taxi cab before he was hired as an Audio Engineer by B. Eichwald & Company to work at the United Nations Headquarters in New York, New York. Andy recorded and broadcasted many world leaders and dignitaries to include former President George H. W. Bush and Bishop Desmond Tutu over his 26 year career as an Audio Engineer at the United Nations Headquarters. Andy retired in June 2004.

https://www.reggaeville.com/artist-details/sylvan-morris/about/

Sylvan Morris

Sylvan Morris is the jamaican sound engineer behind thousand of tunes and some of the best classics reggae albums. From the mid sixties till the 90’s, he shaped a unique sound in the best studios of the island in the sun. He’s done work for artists like Gregory Isaacs, Burning Spear, Augustus Pablo, Dennis Brown, Bunny Wailer, The Heptones, Big Youth, Ken Boothe, The Gladiators, Delroy Wilson and many many more.

Sylvan Morris started his career at the famous WIRL studio (renamed Dynamics later) in 1966. Thanks to Graham Goddall who was looking for a technician to set up some equipment. He worked there for two years and then went to Duke Reid (Treasure Isle Recording Studio) for a couple of months. He was responsible for recording and mixing hit tunes like The Jamaicans ‘Ba Ba Boom’. He decided to leave this studio because the neighborhood and the environment were rather harsh.

In 1968, Sylvan Morris was 19 years old and he joined Studio One Recording Studio at 13 Brentford road. There was a lot of rivalry going on between Duke Reid (Treasure Isle) and Clenment Dodd (Studio 1). Coxsone recruits him because he needs a good engineer to bring out a unique sound and also a good ear to accompany the musicians and singers at the arrangements level. Coxsone used to do a lot of mixing himself, before Sylvan Morris came. He started as engineer but became quickly producer and arranger of a lot of songs because most of the time, Coxsone wasn’t even in the studio so he didn’t know what was happening. Coxsone was focused on auditions. After the Coxsone’s auditions, the artists were in the studio with Sylvan Morris, Jackie Mittoo, Leroy Sibbles most of the time. At Studio One Recording Studio, Sylvan Morris have recorded the greatest singers of that time: Ken Boothe, Delroy Wilson, Dennis Brown and The Heptones to name a few and the best musicians : Lloyd Knibbs, Horsemouth, Phil Callender & Bog Walk (Drum), Bagga & Leroy Sibbles (bass), Jackie Mitto (keyboard), Cedric Im Brooks, David Madden, Vin Gordon & Trammie (horns). When Jackie Mittoo left the ship, it was Leroy Sibbles and Sylvan Morris who takes care of all the work.

Sylvan Morris worked on a two-tracks. “What we actually do, is that we would record the original rhythm the bass and drum on one track, and all the other rhythms on the other track. What we would do then is play it back to the singer, and then record it on another two track because we had two machines. So we would have the whole rhythm on one track, and the voice on the other. And then we probably do another mix to bring the whole together.”

Jackie Mittoo had a lot to do with the formulation of bass lines, when he was there. Sometimes they had a tune, and they wanted to do another tune, so they would use the bass line and turn it backwards! So they would get a sound that audience was familiar with, but they didn’t know where it’s from. Sylvan Morris would play it, play it from the back to the front instead of the direct way. “A lot of people don’t know all the things still (laughs), the same bass, we would use it in so many different ways. We might skip a beat here, put in a beat there, but use the original format.” Sylvan Morris nickname was ‘My Engineer’. Now the reason for that, was that at the time he was very strong in getting the tune to sound a particular way. Sylvan Morris built a bass box and mic it from the back to get that special sound. “To me I always hear a heavier sound from the back of the box, but it doesn’t really penetrate out. If you put a mic there you will get it, and we usually do that. So it had a lot to do with arranging and engineering, cause I don’t think they can get back that sound.”

As far as Sylvan Morris remembers, The Studio One studio equipment was good : Hammond organ B.3 (quite unique on the island), Ampex tape recorder, Pultek equaliser, Sound Dimension echo unit and reverb machines, AKG mic on the piano But others things like the console which was a ‘Lang’ or ‘Long’ wasn’t top of the line. Some of the microphones weren’t sensitive to the bass end of the spectrum, they were more sensitive to the mids and the top end. So they would use them in such a way to get a mixture. It was a unique arrangement, Sylvan Morris had to use his imagination to get the right vibration. “Even the mic of the drums, at the time. The way you mic drums is sophisticated now, having eight microphones or more on the drum, we never used to do that. We had about two, so you would get an overall sound of the drum, you have to place it a strategic spot to get everything. You notice on the tunes that you don’t get the heavy bass drum beat, but then its together, which made the sound so good“. That unique sound came from the actual knowledge of Sylvan Morris and the musicians. Sometines also a singer would come along like Burning Spear. “Burning Spear came by Studio One, one day, he said he had a vision that he should come by the studio to sing. So he came and we listened to the songs that he had, and then go into the studio to create a rhythm to suit them“.

After six intense years of recordings and mixing, Sylvan Morris left Studio One around 1974. He was working a lot, like he was Coxsone’s son. “I got a lot of promises, that didn’t really come about. I’ve lost too much time doing a lot of work, and not collecting enough for it. Coxsone is a very smart chap, it seems as if he exploited the youth. If a man is young, and just coming as an artist he doesn’t know really much. They should have gotten a better deal from him.”

Sylvan Morris became resident recording engineer at “Harry J”, on 10 Roosevelt Avenue, Kingston. He did famous recording sessions like Bob Marley & The Wailers ‘Natty Dread’. Harry J’s studio became one of the most famous Jamaican studios after this session. Unfortunatly in the 2000’s, Sylvan Morris turned blind and needs a helper most of the time.

https://www.reggaeville.com/artist-details/sylvan-morris/news/view/interview-sylvan-morris-at-studio-1/

Interview – Sylvan Morris at Studio 1

04/01/2019 by Angus Taylor

Compared to most forms of music, reggae can take a lion’s share of the credit for elevating the studio engineer to the status of artist or musician. And few engineers in Jamaica can claim to have worked on so many top reggae releases by elite artists as Sylvan Morris. Growing up in Kingston’s Trench Town, Morris’ youthful aptitude for fixing and assembling electronic equipment slipstreamed his route into music: a path that would set the template for the famed engineers of reggae’s offshoot, dub – such as King Tubby, Scientist and Mad Professor. (In fact, Morris went by the nicknames of both “scientist” and “professor” when dub was yet to be born). The adolescent Morris’ technical abilities and golden ears led to mid-60s stints at WIRL and Treasure Isle studios, before he took up residence at “the Jamaican Motown” Studio 1 Records. At 13 Brentford Road he presided over Studio 1’s immortal era, shaping the sound of some of the greatest rocksteady and early reggae sides ever made. Financial dissatisfaction resulted in Morris leaving Studio 1 proprietor Coxsone Dodd to become house engineer at Harry Johnson’s Harry J studio on Roosevelt Avenue. Again, the move proved timely: Sylvan was at the controls for the exemplary albums of the roots reggae period, by Bob Marley, Bunny Wailer and Burning Spear, to name just three. By the mid-80s, when the music was becoming digital, Morris had gone back to the place where he started, the old WIRL site, renamed Dynamic Sounds. There he would stay until his failing eyesight brought him into semi-retirement. He now lives in Kingston, where he needs regular medication and care. Highly opinionated, heavily technical and deeply spiritual, the visually impaired Morris is still a dominant and imposing personality. It’s easy to imagine him as a youngster telling Jamaica’s biggest tastemakers that they weren’t doing their job properly, a practice that cost him his employment more than once. Having worked on so many sessions he doesn’t have much of a memory for details of individual songs. Sometimes the timelines of his tenure at different studios don’t quite marry up to the release dates of the records where he is credited. But while he is not backward in advancing with his own contributions, the picture that emerges is one of a man so skilled in his craft that everywhere he went, the cream of reggae talent followed. Angus Taylor spoke to him at his home in Kingston for this two-part interview. The first half concentrates on the Studio 1 years.

Thank you for taking the time.

Yeah man, no problem.

You were born in Trench Town?

Yes, I was born right at Greenwich Street. Have you ever been down there? You know where the tank is? You have a big tank there. So that is right at the top of Trench Town. Right there is where I was born. 5 Greenwich Street.

Was Trench Town a real singing place when you were growing up? Or was that later?

That was later. What kind of place was it then?

Well I want to tell you now, I have an aunty that lived right down in the middle so she was more like a mother to a lot of the people. But I never stayed down in that section much because I used to live at the top. My father and mother they were living on Lincoln Avenue which is… you ever go down Black Roses? That’s just a little bit above you know?

What did your parents do for a living?

My mother used to do selling you know? She would go to market and buy things and sell them, like foodstuffs. Like bananas, oranges, yams, anything you can think about that had an agricultural feel. But my father he used to work at the telephone company, he was a foreman there. He went away to the States and would go and come. Like on farm work and all those things.

Was his telecoms job technical?

No. It was more like driving.

So were you the first technical person in the family?

(laughs) Well I am the only one in the family! Out of my siblings.

So how did you first get interested in electronics?

There were some books that used to come out called Practical Wireless. Because in those days they were just moving from vacuum tubes to transistors. So these books would show you how you have some circuits and things and how you can build them hobby-wise. So I started from there getting interested in making some little radios.

When did you first build an amplifier?

The first amplifier I built was when I was about 12 years old. I don’t remember if it was 6L was the output at the time. ECC83 but they use that as the preamplifier and the driver. At that time, 15 amps was a whole heap of amps. I think it was the first one I built and I stepped it up after that with some KT 88 you know? Like 100 watts and all that.

Why did you decide to do that and where were the amps being used?

Well it was just me playing them at my home you know? I was quite young.

How did building and fixing radios and amps turn into work?

Well at the age of 15 there was a man by the name of Mr. Martin and he used to do some business. There was a place on Eastwood Park Road by the name of Comtec. So he used to do business with them. Through him seeing me every day with this whole heap of wires all over the place. Sometimes I’d go to church with lights in my pocket or blinking out and things! He just suggested to them saying he has a little relative and if they could take him and train him or something you know? But I could not tell them that I was 15 at that time. In those days you had to be 21 before you could start getting the money and those things there as an apprentice. So he told them and they said “Yeah man bring him come man”. They wanted to get rid of me still but they didn’t want to tell him no! When we went up there they had about 50 radios. And they said “See you we have some radios man? See if you can fix them man.” And within the space of about two weeks I had about 40 of the radios working. So they said “This youth here!” And they said they were going to hire me. So I went on that trip and started to work with them. And within the space of about a month they put me on staff. In those times the taxi cabs and the bauxite companies had these two-way communication radios. The taxi cabs’ radios were called the “reporter”. And you had some of these other more advanced transmitters and receivers and they were used in the bauxite companies. I used to work mostly on the reporters.

They called you the “reporter professor”.

You know the thing man! Yeah man.

Did you love music at that age?

Well let’s put it this way I was more interested in the electronics. So the music came with it, you know what I mean? I did a course down by Kingston Technical to learn radio and TV, where they have the name of Union of Lancashire and Cheshire Institute. That was right in the time when I left Comtec. In between Comtec time and then I reached to Coxsone.

So how did you go from working at Comtec to going to WIRL studio between 1966 and 1967?

What really happened was I had some disagreement with one of the workers. So we parted company. But I was living at a place now where there was this man named Abrahams, he was working at Dynamic Sounds. And I think at that time it was WIRL – it wasn’t Dynamic Sounds. West Indies Records Limited or something. He said to them that “There is this chap and he know a lot about electronic equipment and thing”. So I was asked to come down there you know? So anyway, when I went down there I saw this gentleman by the name of Graeme Goodall. I think he was from England [Australia] and he was working with Dynamic Sounds. They were setting up some studio thing you know? Graeme Goodall was there, he took me under his wings you know? In terms of the music now. So I helped him set up the studio. (laughs) In those times it was about two track to three track. That’s the very early days. And then we left from three track to four track. He and I set up the studio and he started to teach me the rudiments of recording. This was how I got indoctrinated and started to do some work.

Is it correct that while you were there you worked on Judge Dread by Prince Buster and Errol Dunkley You’re Gonna Need Me?

Yes. Yes. Well Judge Dread with Prince Buster and Lee Scratch Perry was on it too, right? But Errol Dunkley You’re Gonna Need Me, that tune the rhythm was not properly done. The tapes were busted you know? So I had to do some configuration, create an intro by splicing the tape like recording it and re-recording it and then splice it and make it into a tune. Errol Dunkley did his tune down there you know? And this brethren was there too – what’s his name? Hold Them. Roy Shirley. Because we did Hold Them too.

Is it right that you left because you were insubordinate to Byron Lee?

No! Well, it depends on who’s looking at it you know? (laughs) One day I was there because it was me that maintained the place you know? One day I was there and Byron came in with his friends. Normally he is a person who wanted to push himself forward. Progressive you know? So he would go run, sit around the board and start turning it up. As I said at that time you had vacuum tubes and all those things so you had white noise coming up through the electronics you know? It’s not like transistors now where it’s silent. So he came now and he turned up the volume and he heard the white noise and said unto me “What you no maintaining the studio properly?” But he turned up the volume full you know? So I looked at him and I said unto him “Let me tell you something sir, if you don’t know what you’re doing, don’t come and trouble nothing here so. Don’t touch nothing if you don’t know what you’re doing.” And I saw him look upon me you know? And he stormed out of the place you know? And within about half an hour I was fired! (laughs) So he fired me but before I reached my home the same man who introduced me to them, he was doing some work for Duke Reid. So the message just reached Duke Reid right away and they hear about “This youth here? Where he comes from telecommunications” right down the line. Duke Reid called for me the same day so I left Byron Lee and went to Duke Reid. And he hired me the same day. You see the next day? Byron Lee sent back for me. (laughs) Byron Lee sent back for me the next day but by this time I was working for Duke Reid. So it goes.

While you were at Treasure Isle you mixed the 1967 Festival song winner Festival song winner by the Jamaicans?Ba Ba Boom by the Jamaicans?

Yes. The festival song. Because he was trying to test me out to see which one of the mixes was better so Smitty who was working down by Duke Reid… He mixed a mix and I mixed my own and thing. I was told that he preferred mine so they put it out. But I didn’t really stay there long. I don’t think I stayed there more than about 3 months.

Why did you move on?

(laughs) Well a sort of similar occurrence to what happened do you know? When I went there Duke Reid said that he was glad for me to come help him out and thing? Because he heard about me as a youth. So when I go me and him were there one day and they were doing a tune and I made a suggestion and he said unto me “Any time you see me a do – you know, produce? You don’t have nothing to say.” So that’s the reverse of Byron Lee you know? So I considered myself and I thought “This man sent for me and he said he heard about me, so I think he wants some help?” I was there about two months and two weeks after that I said “I’m going to leave”. So he said “Why?” I explained to him that the reason. Because he had asked me to come and help him and I made a suggestion and I was sort of embarrassed. As a youth, you know what I mean? Straight from there now to Coxsone – and do you realise that when I went to Coxsone, Duke Reid never stop calling me you know? Saying he wanted me to come back. Because he didn’t believe that I was going to leave him.

A lot of artists told me that they were quite scared of Duke Reid.

Yeah, well he used to carry his gun. He had his long gun in his hand, the rifle and he had a gun at his side, you know? Sometimes he had all two and if the tune them I get away he would just fire two shots. When the vibes reached, you know?

But you were what, 17 or 18 at the time?

Let me see now… 16… Yeah I was I was 17 or 17 plus.

I guess I’m saying you must have been quite confident at that age.

Now I’m going to tell you something. I’m really a spiritual person. I don’t know if you understand what that means? I had an auntie that was a mystic. And she took me under her wings, not necessarily teaching me but making certain statements to me you know? And as a matter of fact I started to study our culture book called the Bible right? So I had confidence within myself as a person dealing with God through what I’ve been reading you know what I mean? So it wasn’t fair then I’m leaving one place to the other, you understand what I’m saying?

So you went to Coxsone and you replaced Syd Bucknor?

Yes. As I entered Studio 1 I think the very same day that I went there Syd Bucknor left. Because he and Dodd used to be some relative, you know?

His cousin.

But apparently he was on his way out it seemed, so Coxsone was glad to see me. When I came he said to me “Boy you come here like my son, so I want you to work here and I will look after you, take care of you, you know? Just work man.” So from him saying that to me as a youth I said “Boy I put down my foot” you know? I did the best I can. I wasn’t rewarded properly but I suppose he gave me an opportunity. As a matter of fact he said to me one day that if I worked with him properly then he can make me a big man in this country. I remember him saying that to me. As I say I worked there for quite a while and pure hit tunes. The way that the studio was set up I rearranged it. To suit my thing. Because in those days you never had a whole heap of electronic echo, there was no digital business in those times there. You had a thing they called the spring reverb which we used to use. So I had read about something and I built a delay system and the delay system was built in such a way that I used to feed the output of the amp and feed it back into the input and it creates an echo. A delay system. You know a bit about the music from Coxsone days?

I know a little.

I don’t know if you listen to most of them tunes you hear, they have a delay. The Heptones and Delroy Wilson. I used to feedback the output into the input and you had a delay system. At that time that was considered to be very revolutionary.

How did Coxsone’s studio setup differ from Duke Reid and Dynamic?

Now I want to tell you. I didn’t really do much recording [at Treasure Isle]. To be totally frank I don’t think I did any recording there. I just did mixing. So it’s really Smitty – you hear of Smitty right?

Byron Smith.

Yes. It was really Smitty who used to do the recording and everything. I might do some mixing. But when I went to Coxsone now that was a totally different thing because I was totally in charge. You had some long, long equipment – it was a long board. I think it was four channels input because we had two longboards that we put together – some Chinese made boards. So you had about eight but I don’t remember if I brought it up to about 10 inputs. But you know at that time it was two track you know? Depending on what we were doing, we might record a rhythm on one track and the bass and the drum on another track and then we’d do overdubs. Sometimes I’ll be putting on horns or some dub on so I’d have to transfer it back now to another track so sometimes it was three generation. Because you have the original then you overdub and then you have to overdub again. To do the voice.

How good an engineer was Coxsone?

Engineer? Coxsone wasn’t an engineer in that time now. I heard that he used to take some tunes, that was before I came there. But from I came there he never did and I’ve never seen him do anything.

How much time did he spend in the studio?

From when I go there I’d hardly see him you know? Because at that time Jackie Mittoo was the arranger and the general producer. So they’d usually probably do some auditions on the weekends and then they would arrange who was going to come in. I think we had sessions about three times or four times in a week. Monday, Tuesday and Thursday if I’m not mistaken.

Did you ever disagree with Jackie Mittoo about the way the music was going?

No sir! No man, Jackie Mittoo was a genius. The man was a… I don’t know if genius is a good word, probably that belittles it. The man could play the organ and the piano together you know? So while he was playing one he would play the next one. And then when he would play the organ, I don’t know how he knew this but on the Hammond organ he had some little buttons where you pull out, you know? To make it different. And I don’t know how he did them so fast you know? He just changed the thing when he wanted to change it! The man was a genius, man. Total genius.

When Jackie was the arranger, who were the musicians you were working with?

That is trouble now. There were a lot of mixtures. At one time you had people like Bagga. There was a brown brother in there I can’t remember his name. You had Eric Frater. On guitar. Bo-Pee. And eventually after a while you had people like Leroy Sibbles.

Yeah he came in a bit later.

A year later on. At one time we had Richard Ace there. One time we had Headley Bennett there too. Benbow.

What about Joe Isaacs and Brian Atkinson – had they moved on by then?

I don’t remember them guys being there. I wonder if they were a little bit before me. You had Horsemouth. And as you know Fil and what’s his name…

Boris Gardiner?

Boris Gardiner used to play a lot of tunes too. You know the thing man. Pablove Black was there too. As you know they call Eric Frater Rickenbacker. You had Trommy.

Vin Gordon.

Yeah, Vin Gordon. And there was this other guy who was the arranger for a lot of the tunes, this trumpeter and I can’t remember his name. He used to do a lot of the arranging after a while when Jackie did leave. Robbie Lyn that was one of the musicians I forgot to tell you about too. Him and Fil came in at the same time you know?

Yes, because they were both part of In Crowd.

Yeah, yeah. And you remember this brethren named Skully? Skully was there with us and he was a musician too. He used to play percussion. And there was this other brethren, I can’t believe I left him out, Denzel Laing. He was one of the percussionist who played on all those tunes there.

I heard he used to bring bits of scrap that he found into the studio to make percussion, chains and things.

Yeah. Everything. Yeah man.

So when you joined it was rocksteady time?

Yes it was just blossoming.

So tell me about some of the tunes and some of the rhythms you worked on.

(laughs) Well I worked on everything! I want to tell you something it’s thousands of tunes you know? Because I spent about 9 years at Coxsone. We would do sessions sometimes three times a week or four times sometimes. And we would sometimes do three or four tunes for the day. And that was a regular thing, never stopped from when I went there. So if you check that for nine years – whole lot of tunes man. Tunes like Fatty Fatty. How Could I Leave. Cables. What Kind Of World. I did the majority of tunes with Delroy Wilson. Alton Ellis. Any tune you can think about, because I alone was there working.

From the musicians that you mentioned it must have been things like Real Rock, Hot Milk, Feel Like Jumping.

Yes. Yes. Yes. That’s with Marcia. And we did a lot with Ken Boothe. Delroy Wilson and do you remember this brethren named Freddie McKay? Picture On The Wall. Freddie McGregor used to sing some tunes too but not much. Because at that time he was really a drummer.

What about Dennis Brown?

Yeah man well Dennis Brown did a lot of tunes with me too. But the first tune we did was No Man Is An Island.

At Studio 1.

Delroy Wilson, Alton, Ken Boothe, Cornell Campbell, you hear about that guy?

Yeah of course! You did Queen of the Minstrel with him.

That man had a phenomenal falsetto you know? Phenomenal, man.

What about Jacob Miller?

To be truthful I think I might have done a few tunes. Love Is A Message.

So tell me what you did to create the unique bass sound at Studio 1.

Ok! Well I had observed from some time before that at the front of the speaker it was more a direct sound but coming from the back it was like it was more round you know? It was like the bass was deep. So what I did I created a box, a speaker box, I don’t remember the dimensions now but I made some apertures around the back. Two apertures. That’s where I put the RCA mic. So sometimes I’d mic it from in front and sometimes I’d mic it from behind. And we also had direct inputs too. So more time I’d use the direct input and the mic from the back. There was this big RCA mic. But this RCA mic here now, it used a ribbon. It has a ribbon and the ribbon got busted so I disassembled it and there was a piece of tape that usually came on the two track tape at the beginning, a piece of silver tape. And this is what I used to reconstruct the ribbon in the RCA mic. So a lot of the mics that were at Coxsone at the time some of them were damaged you know? So what I had to do especially when you put them round the piano and things was I had to go and listen. I listened to the piano and the organ and some of the instruments and listened to how they sound. Because the mic wasn’t really bringing the exact replica of the audio that was being picked up. There were some equalisers called the Pultec equalisers and they were what I used. I sent the signal through them and then because I listened to the sound in the studio, like all the piano and so on, I had to try to recreate the sound that I heard you know? The frequency response at the bass end and middle end and so forth with the equaliser, because the mic wasn’t really picking it up. Because some of them dropped them so much and all of that. So that’s how I came now to become so versed as a mixer. Because I had to listen to the sound and go back in the studio and try to duplicate it. And as you know the even the drum, the drum booth I usually would go in there and listen. And we used to pad the drums like with some shammy and things and then tell the drummer to lick it and then we move it to where I feel is the right sound. And then I’d tape it down and even there were some springs on the drum especially the main drum…

The snare?

The snare drum. So sometimes we had to also tape that because for me personally I didn’t like to hear the sound too trashy so I would always try my best to get it very tight. I’d usually do the taping and make them play the snare and thing you know? And then deal with it from the angle.

Tell me a bit about this story I’ve heard about the Sound Dimension delay and its effect upon the guitar sound.

Well Eric usually had this thing where he played the “check-eh” because I realised that is where the reggae really came from. A lot of people didn’t really realise that. “Check-eh check-eh” he used to do that with his hand. Double it you know? So eventually now Coxsone went away and he must have seen this thing called the Sound Dimension and it was a machine that could record and playback but it used a tape – you had a loop tape. So the same thing that I used to do on the board, that machine was doing by itself. In other words you feed the input and then now when it recorded it you are recording ahead, it records to the loop tape and then it has a playback head so you can move it to get the length of delay that you want. Eventually we started feeding the guitar through that so the Eric never had to do the doubling again. When you play the “check-eh check-eh” you could just move it to adjust it to where you want. Because each tune has a different tempo and you have to get the repeat in the timing.

Yes because I think some people have got confused about the story over the years. They thought that the Sound Dimension delay was what created the reggae but actually it was Rickenbacker doubling the guitar first.

There you go. Oh yeah at the beginning. Well a lot of people try to say what they don’t know. Some people misunderstand and a lot of people try to say what they don’t know because they were being told and sometimes they don’t hear properly or they don’t understand properly.

What other innovations did you create at Studio 1?

(laughs) Well let’s put it this way. I was the innovation. In other words, I became so renowned that I was called “the dancing operator” at one time. I never used to sit down around the board. I’d stand up and every time the music would play and I’d feel it I get up and dance you know? So if a tune would start and they’d not see me dance they’d stop playing. And ask me say what me no like? You understand what I deal with? So I helped out a lot with the time in the vibes because music has a spirit you know? And if you don’t get the time and the tempo proper then you don’t get the vibes. You have to get the tempo, the tempo has to suit the lyrical content and it has to suit the dancing, so it has to have the dance content within it. They would kind of know my feel because whenever I didn’t feel it I’d stopped dancing and they say what happened? What me no like? So I’d always have to give them some pointers.

They say Scratch used to dance a lot to communicate his ideas as a producer. Did he get that idea from being around Studio 1?

Well it is a possibility you know. I don’t want to say what I don’t know but it’s a possibility, because he used to go there and we would work a little bit – not much.

Who was the best drummer that you worked with at Studio 1?

Now I want to tell you something. Horsemouth I think is one of the most steady drummers. And he was innovative too because he would do some ad libs and things. Benbow wasn’t bad. But there was this brother named Malcolm.

Hugh Malcolm.

Yeah Hugh Malcolm. He seemed to be above them in terms of technicality. But I don’t think he was in the reggae that much. But Horsemouth… You’re talking about while I was there right? Fil Callender came after a while, he wasn’t bad, but he was more… he never had so much innovations. So Jackie left and Leroy Sibbles became the arranger. Well, he now was a phenomenon. He would say it too that it was Jackie that mentored him. But he mentored himself too. Because he is a talented individual. When I say talented, I mean multi-talented. So he was a part of Studio 1 because he arranged, he played the bass, he did harmonies. Practically every tune he was in the harmonies.

https://www.reggaeville.com/artist-details/sylvan-morris/news/view/interview-sylvan-morris-at-harry-j-and-dynamic-sounds/

Interview 2 – Sylvan Morris at Harry J and Dynamic Sounds

04/10/2019 by Angus Taylor

In Part 2 of our exclusive interview with Sylvan Morris in Kingston, he recalls his time at Harry J working with Bob Marley, returning to Dynamic Sounds, losing his sight and why his skills and intellect are still in demand…

So why did you leave Coxsone?

Bad treatment. When I went there he said to me that I must work with him and he would treat me good. And after I was there everybody started coming there because everybody came to get a taste of Coxsone. Even Harry J came there to get a taste you know? He promised me a raise on many occasions and it never came to fruition. So I decided to leave and as I said I thank him you know? I thank him very much but he was becoming a bit jealous. Envious. Because some of the tunes that he did not engineer – he wasn’t an engineer – but he started to put his name on it as engineer. But the joke about it was he never wanted to pay me what he said he would and then he wanted to take the credit! He was a man who usually threw one or two punches here and there. But he couldn’t catch on with me because I was lifting weights and he realized that I was not one of those kinds of people. He couldn’t bring that to me so eventually he started trying to little things but it never worked. There was a brethren there working as an accountant so I sent the accountant to him saying that I’m leaving the work. Because from the time he was supposed to give me a raise he never gave me it. So he sent back the accountant and told the accountant to say to me he would double the pay if I don’t leave. So I sent back the accountant to him and told him it is that the makes me want to leave now. Because I’ve been there for 9 years and it’s when I leave and every time I ask for a raise and he’d say yes and he changed his mind sometimes. He’d say he’d give me a raise at the weekend and then he changed his mind. So I said “If it’s when I leave you give me double pay it doesn’t make sense to bother to stay. Because if you offered me double to make me stay you didn’t respect me all the while.” So you left Coxsone – did you go straight to Harry J?

Yes. There was a record shop on Slipe Pen Road or Slipe Road. While I was coming up the road I saw Harry look at me, because he did know me as he came there [to Studio 1] to do some tunes. And he looked out and said “What happened Morris? You want come work for me?” Just like that you know. So as I left, straight up to Harry J I went.

And when you left for Harry J did you find lots of other artists started coming there as well?

Every one of them. When I left Coxsone I got a vision seeing everybody saying that they’d not go back there. They said anywhere I go that’s where they’ll be. So when I went to Harry now I started working with him. But did you know that at the same time that I went to Harry J was the same time again that Syd Bucknor was leaving?

(Laughs)

Yeah because he was working there. Why was he leaving this time?

Was it to go to Channel One?

Well I don’t know… we never question nothing you know? But when I came in, he came out!

Two people who’d already moved from Studio 1 to Harry J were Bob and Marcia. Marcia told me that Harry J used to come down to the gate of Studio 1 and asked her to leave.

Yes yes yes. Well even the Heptones came up there and did some things because even this tune Book Of Rules it’s by Harry J we did it. That tune was a unique tune. As a matter of fact the Heptones said they came there for me to do the tune. So when I heard the tune at the beginning it sounded so beautiful man. But when I started to mix the tune it came like the sound changed. So what I had to do was take back all the equalisation and just bring up the levels, the faders, until I heard it sound the way it sounded to me and then just tweak. Just barely tweak. A very unusual tune there that tune, Book Of Rules.

So how was the set up at Harry J different from Studio 1?

Well, he had eight track you know? So we had eight tracks there and eventually we went to 16. Because I think Harry had some arrangement with Chris [Blackwell]. Chris he was involved in the music from all over the place. So I think he must have helped him out. We got a board called Helios board, so this is totally advanced from Coxsone.

So you came to Harry J after he did Liquidator?

Yes, I was after that.

But when you went to Harry J dub music was taking off… You would release some dub albums 1975’s Dub Wise (Morris on Dub), Reggae Workshop and 1978’s Cultural Dub.

Well let’s put it this way. It’s started to take off from Coxsone you know? Because what caused the dub thing now, Black Arrows and Prince Patrick and all of them and when he had sound clash they used to come and ask me if I had any tunes that I can give them. So I might play some tunes and they would select a tune. What happened was we used to cut dubs down at Coxsone too you now? Dubplates. So I would give it to them up on a Dubplate and they carry it down so they could mash down another sound or conquer them. Now the next sound now would send in some spies because more times when we gave them the tune and gave them a name, they changed the name you know? So they were sending some spies and when the spy would go in to find out what the tune was named. Because if they used the tune to mash them up they’d want to get the tune too. So that’s how come the dub thing started. What happened is sometimes a man would go and he would see the name of the tune up on a Dubplate and when he’d come and ask for that tune, we didn’t know the tune by that name so we didn’t know which tune he would talk. So then he’d have to hum it or have a horn phrase or something. So what we started to do was we had to give them a different style. So we might give one with the pure rhythm and thing and we might give one with a little drum and thing so the drum and bass thing started. I want to tell you some of them also suggested it too, like “Cut out a little of this you know?” So eventually we started to go with it. So the dub thing started.

So Bob and Marcia had already started to have some international success from Harry J. They started to travel.

Yes, yes. And they started to put strings to some of the tunes.

Obviously Bob Marley did a lot of recording at Harry J – the albums Catch A Fire, Burnin’, were part recorded there and you worked on Natty Dread and Rastaman Vibration.