https://www.reggae-vibes.com/articles/2019/01/interview-with-scientist-part-1/

https://www.reggae-vibes.com/articles/2019/02/interview-with-scientist-part-2/

https://www.reggae-vibes.com/articles/2019/03/interview-with-scientist-part-3/

December 30, 2018, Los Angeles

By Stephen Cooper

PART1

Mr. Brown, thanks again for taking the time to do this interview. I understand you just came back from doing a few shows in the U.K. with Winston Williams, also known as “Horseman.” How did that go?

It went very well.

Seeing as you were present in mostly all of the top recording studios in Jamaica when roots reggae and dub were born, and when many believe they peaked, in the 1970s into the early 1980s, and, that there’s no question [that] history will record you as [being] one of the greatest innovators and pioneers of the music, I have a lot to ask you today!

Okay.

As you said when we scheduled this interview, there exist many falsehoods and misconceptions about yourself and your highly distinguished career, many of which I hope we can address.

Yes.

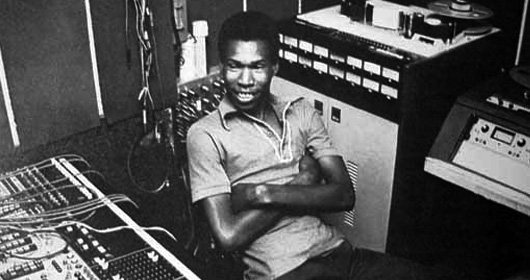

Just to clear up some basic biographical information, I want to start with your name. Not the title of respect “Scientist,” by which everyone knowledgeable about reggae and dub [music] knows you. The story of how [famous Jamaican music producer] Bunny [“Striker”] Lee, together with King Tubby, christened you “Scientist” because your ideas about mixing and recording music, as well as the technological possibilities of the mixing console (including things like “moving faders”), were more advanced, and more predictive of the future of Jamaican music, and one could argue [by extension], all music, [than anyone else, even though you were but a teenager] – that story has been well told! But, in reading about you, I noticed that journalists and writers alternatively refer to you as “Hopeton Overton Brown,” “Overton Brown,” “Overton H. Brown,” and other similar permutations. What is your full birth name?

My full birth name is “Hopeton Brown.” Those who know me from kindergarten know me as “Overton.” My Jamaican side of the family all call me “Overton.”

How come?

My grandfather mostly used to call me “Overton.” So anybody who knows me well from short pants-days, they know me as “Overton.”

Now I read that you were raised in a fishing village called Harbour View, near the Norman Manley International Airport in Kingston[,] [Jamaica]. Is that accurate?

Yes, that’s very accurate.

And is Harbour View also where you were born in 1960?

No, I was born in a more western part of Kingston. My first remembered residence was [on] Waterloo Road.

What was Harbour View like growing up? What are some of your fondest memories of it?

Learning how to smoke weed. (Laughing.) [And] I learned about His Majesty, Haile Selassie [I]. [Which] helped me to change some of my ways. Because I was getting ready to be on the wrong side of life. I met a couple of Rasta people out there. And they taught me about colonialism. [About] [h]ow the world is run by certain individuals, and what real Babylon was. So after that, I started to go on the right side of life.

Now in an interview with DJ 745 last month in the U.K., you said you grew up with your grandparents.

Yes.

Specifically, you said they wanted you to grow up to be one of “those people [wearing] a suit and tie.”

Yes. A lot of people grow up with a misconception that everybody in Jamaica smoke[s] weed. My grandfather was a police inspector. I was the embarrassment to the family.

Wow. [You were the] [b]lacksheep?

Yeah. They wanted me to take the bar [exam] like you, [become] a lawyer like you. [But] I hate suits. I hate dressing up. I couldn’t wear the uniform every day. I didn’t like going to church [and] dressing up every Sunday, choking [in] a tie. And then I would notice the same pastor pass all of us at the bus stop baking in the sun. Or getting wet in the rain. And he alone [was] driving an expensive car going to church.

Hypocrisy?

Hypocrisy! And then he talking about “oneness” and love.

I was curious whether you lived under the same roof with your grandparents –

Yes.

– and also your father and mother?

[Just] [m]y grandparents.

Did there come a [time] where your family saw [that] you were successful in music and accepted what you were doing?

Later on in life they started to accept it. Because one of the misconceptions was, whenever you see King Tubby in the newspaper, that he was part of a gang. Because every weekend you’d read in the newspaper [that] King Tubby’s sound [system, Tubby’s “Hometown Hi-Fi”] got shot up; police caught all these people with all kind of weapons. So my grandparents thought that [King Tubby] was influencing me the wrong way. I remember one day my grandmother run up to him and say, “You, you! Stop! Stop giving my grandson that thing to smoke!” Poor Tubby. He [didn’t] even smoke cigarettes.

Now I thought that Tubby’s sound system, [his] Hometown Hi-Fi, was one of the [sound] systems that, despite all the politics and the gangs that were clashing, that [Tubby’s] was one of the [sound] systems that everyone respected. That it was apolitical. That either side, PNP or JLP[, the two main political parties in Jamaica], would respect Tubby’s system, because the sound was so good?

Yeah, but not the police. Not the police. The police would actually destroy [Tubby’s] [sound] system.

Now I understand that your father worked full-time in electronics, and that at around age 14 you also developed your own interest for electronics by experimenting with old electronic parts you got from your dad. True?

Yes, that’s true.

And did your father work at the same electronics store where you got a job yourself as a teenager, on Orange Street, a few doors down from where Bunny Lee had his record shop?

No.

He worked at a different shop?

He was freelance. A television technician [in the neighborhood].

The [electronics] shop where you ended up working, just to confirm, was called “Lens Radio Electronics,” true?

Yes. Seems like you did a lot of homework. (Laughing)

(Laughing) I tried to. When you dropped out of school as a teenager to work at the electronics store, and also, to build and test amplifiers for local sound systems, did your mother and father support this decision? You talked about your grandparents, but I’m curious [also] about your mother and father, especially your dad. Because he was involved in electronics.

Yeah, they were more impressed. But my grandfather, being that he was a police[man], he remembered back in the day when [you] used to go to Waterhouse, it was like a “no man’s land.” And then when they discovered that I’m not going to school – I used to pretend like I was going to school. And then, one day my cousin didn’t catch the mail for me. And the mail went straight to my grandmother. “Hopeton Brown has not come to school in six months.”

Wow.

When I went home, my grandmother said, “how was school today”? [And I said,] “Good, Grandma.”

Oh man!

And, [she said,] “How’s everything?” [I said,] “Good, Grandma.” And she said, “Go get ‘Willy.’” She called the belt “Willy.” I got a whipping from everyone in my family that day.

Wow, Scientist, wow. Well, at least you survived. And you’re still here to talk about it (Laughing).

(Laughing) It didn’t stop me. I got so much punishment. But after a while [they] got fed up of beating me. Because it didn’t make any sense. Because I’m going to go to the [music] studio. I’m not gonna go to school. I don’t want to learn about Christopher Columbus.

You followed your passion, music?

Yeah. Yeah. And after [a while] they leave me [alone]. But I was the embarrassment to the family. I was the person in the neighborhood – “don’t mix with that kid, he’s mixed up in gangs, he’s going to Waterhouse – ”

[He’s a] [b]ad man?

Bad man-business. Poor me. I was never in any gang.

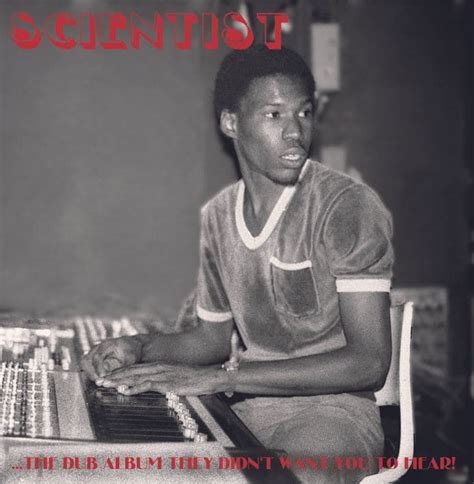

Many past interviews you’ve given have addressed the specifics of how several things King Tubby was doing [sonically] with his “Hometown Hi-Fi” sound system, and in his home studio (at 18 Dromilly Avenue) that really appealed and spoke to your technological curiosity, and further, that it was this interest you had in [the] albums Tubby was making, like “Roots of Dub,” together with introductions and recommendations from Bunny Lee and another friend of yours that led you to working with Tubby. Now, I do want to clarify a few things here. Is it accurate that you were only 16 when you first started working for Tubby, testing and repairing amplifiers, speakers, and other electronics?

Yes.

And before you began working with King Tubby, you already had experience working at Studio One for the legendary [Clement] Coxsone Dodd, true?

Yes.

When did you start working with Coxsone – even before [you started working] with [King] Tubby?

It was on and off. Before and after. Because I was neither full-time at both places.

I’m asking these questions because it seems, truly, you were a child prodigy as a sound engineer to be doing that at such a young age. And I want to explore a bit with you, Mr. Brown, the complex relationships that existed between King Tubby, yourself, King (then “Prince”) Jammy [also known as Lloyd James], and even some of the other famous sound engineers associated with King Tubby’s Studio, like Philip Smart, and [singer] Pat Kelly. Because other than Lee “Scratch” Perry, Errol [“T.”] Thompson, and perhaps also Prince Buster [Cecil Bustamante Campbell] too, [it was] Tubby’s studio [that] was really the birthplace of dub music in the world. And yet, still, there seems to be a lot of inaccurate thinking and reporting as it concerns the dub tracks that were cut at Tubby’s; who was doing the bulk of the mixing; and, the relationships that existed at the time between Tubby and his principal engineers (I mentioned), including yourself. In just about every book, documentary, [and] article about dub music, even panels and conferences you’ve been invited to participate in, you are often introduced or described as having been King Tubby’s protégé, or his apprentice. And Jammy is often described as having been Tubby’s “right-hand man,” the heir apparent, and Tubby’s most accomplished engineer. But you have been pushing back in recent years, and in stronger and stronger terms, against this commonly recited version of events. True?

Well, first of all, Jammy was very unreliable. That’s how I got my first break. Because he was supposed to come to the studio to do a session with Henry Lawes, and because I was a kid, Henry Lawes did not want me to work on it. And Tubby said: “The only way you gonna get this record mixed or cut is if you make ‘him’ [myself, Scientist] do it, because I am not doing it.”

And Jammy can’t be found?

He can’t be found. He was very unreliable. Jammy was never ever Tubby’s “right-hand” man. The only person that touched the money at 18 Dromilly Avenue was I [and] King Tubby. The only person that had a key to 18 Dromilly Avenue was I and King Tubby. The “Princess” (referring to Jammy) perjured herself in the United States second district court. When the Princess came to court perjuring herself saying he was my boss, he was one of the three directors [at Tubby’s studio] – those are lies!

And I’m definitely going to ask you a number of questions about your litigation with [the] Greensleeves [record label]. And feel free to say whatever it is you want to say about it, but I wanted to point out that on the issue of the misconceptions about the relationships at [Tubby’s] studio, you were interviewed [in the U.K.] by Lioness Izasha, and, when she said, “you’re known as King Tubby’s apprentice,” you pointed out, “King Tubby wouldn’t allow someone without full knowledge and experience to use his mixing equipment and to operate the studio.” Sarcastically and rhetorically, you questioned: “[A]nd they want to call me an apprentice? And I was doing all these things? Wow.” And 10 years ago, in an interview with Angus Taylor for United Reggae, you were even more direct on this point. You said: “Jammys do not have my experience. What live concert Jammys ever mixed with twenty-thirty thousand people? The only place Jammys ever worked was around King Tubby’s at that little piece of hell hole, he set up around there. He doesn’t have my experience. Not even Osbourne Ruddock [(King Tubby)] has my experience . . . working on different types of consoles.” And you’ve pointed out over the years, in a number of different settings, as you [also] just did, when you worked with Tubby, Tubby gave you the key to the studio. And [he] trusted you with collecting and holding the money, not Jammy. And you’ve said before that Tubby’s told you in front of Jammy, don’t allow –

“Don’t allow him to touch the money.” And, “Don’t allow him in the studio by himself.” Yes.

And you’ve said quite clearly that you were the one running that place [(Tubby’s studio)], but it’s just, because you were so young [at the time], and because you weren’t in any way protected legally, folks have taken advantage of you in terms of reciting th[e] history [of dub music’s roots]? Am I accurate about this?

Yes. Very accurate. Let me make it clear: there were other people there; thank God to somebody like Pat Kelly, who I can salute, one of the guys in reggae that’s very decent. [He’ll tell you,] Jammy was never my boss. And what used to happen [is] at nighttime, Tubby used to leave the studio from about three or four o’clock in the afternoon. He would only come for about an hour. And then, at nighttime, Bunny Lee would work, and Pat Kelly would be working for Bunny Lee. And Pat Kelly would be mixing the “A” side [of a .45]. (Calling Pat Kelly on cell phone) I’m trying to see if he’ll pick up a call right now. Hello Pat Kelly?

Pat Kelly (by phone): Uh-huh?

Hey, we’re doing an interview here and I was just mentioning what went down with me and you [and how] at nighttime you’d be mixing for Bunny Lee, and you’d mix the “A” side, and then you’d allow me to mix the “B” side of the tracks.

Pat Kelly (by phone): Uh-huh.

Yeah, because people have a lot of things twisted. A lot of people don’t know that you mix, and that you’re also an engineer.

Pat Kelly (by phone): (Laughing) Yeah.

Yeah. So I was just trying to mention you in the interview –

Greetings Mr. Kelly! My name is Steve Cooper. I’m hoping someday I can meet and interview you, too. I’m writing a book about reggae music.

Pat Kelly (by phone): Yeah?

Yeah. And so I’ve been meeting with all the most famous [and emerging reggae artists] including Scientist, Lee Scratch Perry, King Yellowman, and, and everybody. So I’ll get your contact info from [Scientist] if it’s okay, then maybe I can catch up with you at some point?

Pat Kelly (by phone): Okay.

Give thanks, Mr. Kelly!

Pat Kelly is one of the people you should interview. Give thanks, Pat.

Pat Kelly (by phone): Okay. Alright. (Hanging up phone.)

So Pat Kelly was the one mixing a bunch of tracks at nighttime. And because I was the person to lock up the studio and make sure everything [went] well after Pat worked, Pat would say: “Hey, hey, come on man, you mix the dubs.” And I would mix the dubs. So Bunny Lee and [Pat] would mix the “A” sides. But, during that time, Jammy was never ever allowed in the studio by himself. Why? Because we used to have a guy there, we call[ed] him “CIA.” (Laughing) [And] Tubby would say: “So CIA, what time you leave the studio last night?” [And CIA would say,] “like 4 in the morning.” And Jammy would tell Tubby he left at twelve. (Laughing) So, Tubby was a very smart guy.

Was there ever a point early on when you and Jammy were friends and had a mutual respect?

Not really. Not really. His brother –

Jammy’s brother?

Yes. Trevor. Looked just like [Jammy]. If you don’t know them –

Does he do music, too?

Yeah, he produced a song that ended up in some kind of family feud – Jammy tried to take credit for it.

[What] was the title of the song?

“I Know The Score.” By Frankie Paul or one of them that he did. That he produced. And [it was Jammy’s] brother [Trevor that] I had a better relationship with. Because Jammy has been always jealous. And he couldn’t understand why I had such control over the studio when he grew up at Tubby’s. But Tubby’s mother, “Ms. Sissy,” is what people don’t talk about. She would come in front of Tubby and say, “I don’t like Jammy.” And Tubby listened to his mother, like most sons listen to their parents. And she would confront him. All the bad guys in the neighborhood, the gangbangers, it’s like when she come around, it’s like the queen come around. They’re all helping her get off of the bus. Carrying her groceries. [And] [s]he – she would cook for me in the evening and invite me over for dinner.

So you had a strong relationship with [Tubby’s] mom?

Yeah, with [Tubby’s entire] family. Tubby’s wife, his daughter . . . . (laughing). Only one thing Tubby say, “You! You’re not getting into my family. Leave my daughter alone! (Laughing)

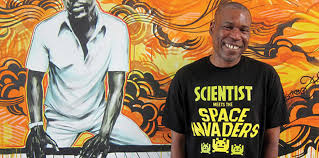

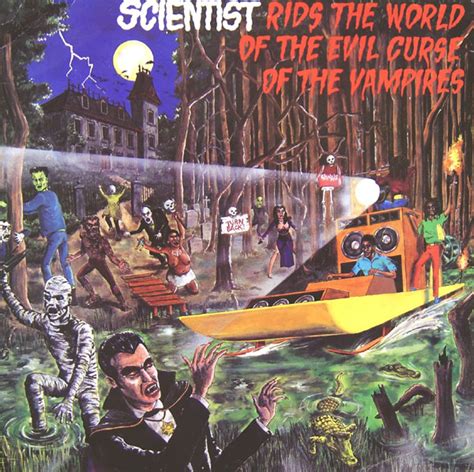

Now on Valentine’s Day in 2015 you published a very detailed post on Facebook in which you very clearly outline your position concerning your dispute about the 6 dub albums [“Scientist vs. Prince Jammy,” “Scientist – Heavyweight Dub Champion,” “Scientist Meets the Space Invaders,” “Scientist Rids the World of the Evil Curse of the Vampires,” “Scientist Wins the World Cup,” and “Scientist Encounters Pac-man”] that [the record company] Greensleeves released in the early 80s, without paying you a dime. And again, you also [stated] your position on this in a 2008 interview with Angus Taylor for [the online magazine] United Reggae, but, [have] there been any additional updates or legal developments in [your] [long running legal] dispute with Jammy, Greensleeves, Blood & Fire, VP [Records], etcetera, [concerning your allegations about the theft of your intellectual property and royalties from those 6 dub albums]?

Let’s look at what makes sense, alright? You’re an attorney, right? And for thirty years these albums [have] been out. They try to rename the title[s]. And when you look at it, the person who came to court to lie for them, who perjured themselves for [these record labels], is the one [given] credit [for] the album [and on the album cover] when he didn’t have anything to do with the album. So there is a conflict right there in court, right? Where the worker is now testifying for his boss. And then the worker there didn’t have anything to do with the[se] album[s], but yet still they think that they owe him some kind of loyalty.

Are your lawyers still pursuing this? Because people haven’t heard mention of this [in the news] recently, and I wondered if you’re still pursuing [the vindication of] your rights on this?

Well, yes. Because, you’re a lawyer as I say, you know what it is to be systematic. When the courts see you as systematic. This is something you are continuously doing.

Litigation, especially civil litigation, takes forever. And I think you’ve said before, and I completely understand, some of these companies, what they do [is try to drag things out], because the litigation costs so much to keep pursuing it – just the cost alone to keep pursuing it – [that] it can be prohibitive. Especially so for artists, I would think.

Yes. And then what you have, you have lawyers that are involved in what’s called “willful blindness.” As an attorney, you know exactly what that means. But for people who don’t understand: if you’re working at a mechanic shop and ten years go by and you’re just answering the phone. You know what these guys are doing in the mechanic shop, but you still choose to work there. So it becomes “willful blindness.”

Even though the drugs may be moving in and out of the backdoor –

In and out of the backdoor, but you just answering the phone? After a while it becomes willful blindness. And what I find is a lot of attorneys, or some attorneys, they don’t apply what you call “candor.”

That’s for sure. I’ve noticed that in the legal profession. I agree with you 100%, Mr. Brown.

Rule 3.3 [of] the American Bar Association –

(Laughing) Wow! When are you going to start practicing law? You know the law, Mr. Brown – I can tell. You’ve been involved in this fight for [a long time]?

Well, here’s what I know: I’m not a lawyer [just like] I’m not a mechanic, but I know about cars. My specialty is electronics but you find that a lot of these attorneys do not practice candor. Rule 3.3, when your client is about to commit perjury, do something illegal, you have to deter the client. If that doesn’t work, you have to tell the judge. And if the client still wants to go forward, you have to drop the case.

Laughing) If you ever want to practice law, Mr. Brown –

The judge wouldn’t want me because I would be smoking too much weed. (Laughing)

Selecta Jerry, a DJ in New Jersey, sent me a picture of a vinyl pressing [put out] by VP Music in 2016 of [the album] “Scientist Rids the World of the Evil Curse of the Vampires.” Now as Selecta Jerry observed, it has much of the same artwork that was on your famous album released [in the 80s], except for now, [the album] has been retitled. It doesn’t have your name on it. [Instead,] [i]t’s called: “Junjo Presents the Evil Curse of the Vampires.” And then[, adding insult to injury,] your image? Where you’re at the mixing board? It’s [been] blocked out [entirely] by a big [search]light. You wouldn’t have any idea by looking [at the artwork] that Scientist was involved in [the making of] this [album]. Now, in a 1998 interview you did with Mike Pawka, you said that [this album,] “Scientist Rids the World of the Evil Curse of the Vampires” is one of the best, and [also, your] personal favorite album of all of the [many] albums that you’ve made. Given that, how do you feel about the album cover being manipulated in the way that it has, and also, [the fact] that, if you go on iTunes, a person who is interested in dub music, that is the album that pops up, the “Junjo Presents” [version] without [any attribution or credit to you]? Because [personally], I think this is one of the best [works] of music ever created. And it’s very disturbing to me, and I can’t even imagine as the artist who created it how you must feel about this.

Well, here’s what: We had a court ruling that came down against [these infringing record companies] in France. And the illusion that producers own copyrights – do you know about the Berne Convention?

Only because I read about it on your Facebook [page]. (Laughing)

Yeah, well in Jamaica and [also] in the United States, [as signatories] to the Berne Convention, anything having to do with drawing, architecture, music, sound recording, anything that you create [there are only a certain number of ways under the law that ownership can pass]. And when we were in court in France, I showed the judge the law. And I asked the judge to rule on the law. The judge ha[d] to [follow] the law. So [these infringing record companies] thought by taking this Lamborghini, [and] painting it black when it was red, and calling it something else – well, when the cop stops it, it has the same VIN number. It has several VIN numbers written all over the car. See the judge has to rule on the law. And when lawyers are involved in willful blindness, and then, when lawyers start to be a part of the crime scene, you know as a lawyer, how the judge feels about that.

Now another related but independent issue concerning the theft of royalties from you, and perhaps the equally or more important theft of recognition and historical musical legacy, concerns many of the same [record] companies we’ve already mentioned, and others too, releasing dub mixes, especially with the famous session band the Roots Radics, but crediting and putting King Tubby’s name on it, not yours. True?

True. Listen to what makes sense: Why when Tubby was alive, none of these albums came out? Doesn’t make any sense, right? Why after Tubby died all these albums just suddenly appear? And then here’s what, you remember that stuff that Tubby put out with [Anthony] Red Rose and them? Where all that sound went to? You know what happened? I set the bar so high, that not even Tubby could reach that bar. That’s what makes sense.

[Y]ou’ve said [this] before, and others have [too], [that King Tubby didn’t do as much] mixing as [some] folks [have been] saying [all these years]? [That] [h]e stopped mixing.

The last song Tubby mixed for anybody was [Barber Shop Saloon/]“Weather Ballon” with Mikey Dread. And I used to say, Tubby don’t want to mix. Why? Why? Why he doesn’t want to mix. He’s like me now – I don’t really want to mix your song, man. And he would mix none of these songs. But here’s what happened: the bar that was set, and the expectation. Not to be disrespectful, but because the bar was set so high, everybody – and then the misunderstanding about Tubby’s thought. First of all, Tubby [didn’t] deal with apprentices. You either know it or you don’t know it.

That makes sense to me. There’s no time for that in the music business.

No time for that in the music business. You either ready or you’re not ready. But the bar was set so high.

In my research on this, I was particularly perplexed by the TV show “David Rodigan Looks at the Life of King Tubby and the Influence of Dub on Today’s Music.” It aired on BBC1’s “Extra Stories” and is easily found on YouTube. Narrating the show, Rodigan asserts, quote, “Hundreds if not thousands of dubs were cut by [King Tubby],” and, that “Tubby mixed thousands of records.” What’s your reaction to these assertions by David Rodigan?

Look here. He was not there. He’s going by hearsay. That’s the first thing that makes sense. Why, when King Tubby was alive, none of these albums came out? Why?

I noticed that [in March 2014] you posted to Facebook: “These are the only legit [King Tubby] albums” [on the market]. Then you listed three albums Tubby should be credited with: (1) Dub From the Roots; (2) Roots of Dub; and (3) Tommy McCook’s “Brass Rockers.”

That’s the only three albums.

And in June 2013 you posted an old interview [originally posted] by “Silver Kamel” [and available] on YouTube of Bunny Lee. It’s only about twelve minutes in length, but in there is so much critical history of reggae and dub music. It’s a must watch for [anyone] interested in the history of the music. It explains so much. And in this interview, Bunny Lee [says] exactly what you, Scientist, have been saying for many, many years now: [King] Tubby did not mix thousands of dub tunes as David Rodigan and others have asserted – including a number of record companies that have been releasing [all kinds of reissued] albums with Tubby’s name [on them]. The truth of the matter is, many of these dub mixes put out after Tubby’s death, and marketed under Tubby’s name, are actually Scientist mixes. [Work] [f]or which you’ve received no financial compensation. Is that true?

Yes. This is what I don’t like with Jamaican producers. Jamaican producers [have] got things twisted. You might own the master tape, but what was the producer doing? Standing up in the studio giving [out] high-fives? And so the Jamaican producers are just looking for new ways to make money. And guess what? When you talk to [legendary bass guitar player] [Errol] Flabba Holt [for example], [ask him] about how the producers register everything 100% to themselves. So Flabba Holt don’t get no money. Pat Kelly [is] going through the same thing. First of all, you can’t have a contract with a dead man. When the artist is dead, you have to settle the estate. And, you see, they don’t like to deal with me. Well you see, I have a contract. The person died. So a dead man can’t enforce his contract. So I say, “what are you talking about?” Well you can’t have a contract with a dead person.

I have trouble imagining the frustration you must feel about these issues. Now nothing I’ve said, or [that] you’ve said, or that Bunny Lee said in that interview [posted by Silver Kamel], is meant to show any disrespect to King Tubby and his legendary and tremendous contributions to Jamaican music. And, as you’ve said before on numerous occasions, you had a tremendous relationship and a mutual respect with Tubby?

Yes.

Indeed, in a September 2001 interview you did with Michael Veal, associate professor of ethnomusicology at Yale University, you said: “Tubby’s [sic] is somebody I saw every day of my life for about five, six years. Not a day passed and I didn’t see him. We was very close. A lot of people thought I was his son!” And so despite the fact that you have publicly complained about the release of dub mixes you made, that have [been released with] King Tubby’s name on them, that hasn’t dampened at all the fondness of the memories and the bond you had with King Tubby – true?

True. Look here, Tubby gave me a break, one of the biggest breaks in life. Without any doubt. A lot of people couldn’t believe it. Tubby allowed no one to touch his money –

But you. A young kid like you [were, at the time]?

And guess what? My two pockets filled with money every day. In the middle of Waterhouse [an economically depressed, but artistically rich area of Kingston]. And not one person ever bothered me. Not one person ever bothered me about money, or tried to rob me. But I was not a part of a gang. I was running the studio. And when you look at what makes sense, where was Jammy’s name during that time on the albums? Where was Tubby’s name during all that Greensleeves time on the albums? Why? Because [I] set the bar so high. Why after I left Jamaica all that stopped?

Part2

Now [in the first part of this interview] we mentioned briefly King Tubby’s famous “Roots of Dub” album. That’s an album that there’s no question about whether Tubby mixed it – he did.

It’s a big inspiration until today to me. Every time I hear that album it carries me right back to day one.

And I love that album too, and [I understand that] that album was one of the reasons you were drawn to Tubby’s in the first place –

Yes.

In a 2012 interview with Boomshots, you were asked whether Tubby’s “Roots of Dub” [album], or Lee Scratch Perry’s “Blackboard Jungle Dub” was the first dub album in the world. And at the time, you said, candidly, that you weren’t sure, but that you were sure [that] Tubby’s “Roots of Dub” album was the most known. I don’t want to revisit the age-old debate about which was the first dub album – both are terrific – but [I want to ask you this question] because I interviewed legendary percussionist Larry McDonald recently [, in October,] after he and Scratch played at the Dub Club [in Los Angeles] to celebrate the 45th Anniversary of the Blackboard Jungle Dub’s release. And [so] I asked Larry: How involved was King Tubby in the final product that is the Blackboard Jungle Dub? As some people have suggested – I believe David Katz [, for example,] the biographer of Lee Scratch Perry – that Scratch has downplayed Tubby’s participation in the mix of that [famous dub] album. And Larry McDonald said specifically that he didn’t know, but that Philip Smart might know, though [Philip Smart] has passed on. And then, Larry said, “You know what, Scientist might know the answer to that.” So here I am with you and it’s a great time to ask.

Candidly, I have to say, I don’t know. If I hear it – but look at what makes sense. Why is Scratch not mixing any albums now? If I hear it, I would have to hear it to remember it, I could tell you if it has King Tubby’s signature.

Well hopefully, sooner rather than later, when we meet again, I can play it for you or ask you before we meet to listen to it closely. Because there has been a lot of speculation about the Blackboard Jungle Dub and how much of a hand King Tubby had in it.

Well I met Scratch at Tubby’s. I know his wife, Pauline.

His ex-wife?

His ex-wife, right, Pauline. Scratch was – yes, Scratch was responsible for [the rise of legends like] Junior Byles, Bob Marley and [many other performers]. As far as the Blackboard Jungle Dub, I would have to hear it.

Okay, we’ll revisit this question then.

Yes.

Do you maintain contact still with any of the surviving members of the Roots Radics, the session band you had so many hits with? I believe Flabba Holt is playing bass, and that Dwight Pinkney is playing guitar, for Israel Vibration these days? And I believe percussionist Christopher “Sky Juice” Blake may still be alive, too? And I guess I wanted to ask you if you thought these would be good people for me to talk to?

Yes, I’m still in touch with Flabba. (Calling Flabba on his cell phone.) Yo, Flabba?

Flabba Holt (by phone): Hello.

Yeah, we’re doing an interview here, and I was trying to set the record straight about what you did.

Hey Mr. Holt! This is Steve Cooper. I write about reggae music for Reggae Vibes and several other publications, and someday, I [plan] to write a book about reggae music. And [so] I’m hoping you and I will get together [for an interview]. Right now I’m interviewing Scientist[, in part,] about some of the misconceptions that exist about the mixing that was done at King Tubby’s studio.

Flabba Holt: Yeah man. Scientist is the champion of dub mixers. Tubbys was a good mixer you know, but Scientist really carried dub, especially Roots Radics dub. Scientist really make the dub thing carry on officially, you know? You understand?

Yeah, I do. But one last thing I want to ask before we say goodbye is, what is it like working with Scientist? How was it that you guys were able to produce such crucial music together, and to really make dub explode in ways that no one could ever imagine?

Flabba Holt: (Laughing) Yo, mi a tell you already, mi a tell you again, you know? (Laughing) You see, Scientist, he is the man. Scientist – that man create dub. I and I – Scientist make the dub thing [with the] Roots Radics. The Roots Radics riddim, that, Scientist a-build. Scientist a-make the dub thing fi really work. Because no one knows it like Scientist. You understand?

Yes. Give thanks, Mr. Holt! (handing phone back to Scientist who says goodbye and hangs it up.) Now [two] people who follow me on Twitter, “Gong’s Pinnacle” (“@RasThaFarEye”) and Dominic Ali (“@domali3”), wanted me to ask you how you felt about dub music being more popular and much more heavily produced in countries other than Jamaica, where it was born. Of course, I know you’ve discussed this many times in other interviews – including recently [in the UK] with DJ 745 – but it’s such an important issue when it comes to celebrating Jamaican culture, I feel it’s worth asking if you have anything more you’d like to say on the subject?

It’s a disgrace. Dub comes from everywhere but Jamaica where it was created. And when you look at what makes sense, I am not there anymore. Tubbys got murdered. And when you look at what makes sense, “Princess” is still there [referring derogatively to King Jammy]. So why is the Princess not making any more dub albums? Why? And here’s why: There is a formula – and don’t get me wrong, you have the musicians like Flabba Holt, they are very important. But the engineering technique – that I didn’t really show anyone else – everyone back there [in Jamaica] was trying to look over my shoulder, and trying to figure out the technique, including King Tubbys. I didn’t choose it, it chose me. After I left, the day I left [the famous] Channel One [studio in Jamaica], it closed the next week. Or the following week.

You went to Tuff Gong [Studios]?

Yeah. And then Tuff Gong became the place where everybody and their grandmother who never worked there, started to work.

And in fact, Professor Veal [at Yale], who interviewed you in 2001, wrote in his book about dub music that you could see by the number of [artists] who were coming from Waterhouse and other tough areas, were suddenly, many of them, were suddenly moving over to Tuff Gong

whereas they used to go to Channel One [to record], now they were coming to Tuff Gong.

Yes. Why?

Because you had moved there?

That’s the only reason and what makes sense. Because here’s what happened: When I used to leave Channel One – I used to just go up there just to hang out with the Wailers, with Carly and dem, and smoke weed – and one day I was in the studio and [the late] Willie Lindo said to me, “Look here, man, I see you with that smile. You have something that you know you’re not telling anybody.” And I was there smiling. And him say, “What is it, man? Come on, tell me! Tell me what it is.” And I say, here’s what you do Willie Lindo: “Book the studio, and I will show you. And I come like this, “See this button right here, Willie Lindo?” They all been mixing Bob Marley, everybody’s song in “monitor mode.” The [mixing] console has several different modes and positions. And bingo! Then they start to get the same type of sound like we got at Channel One. And then everybody and their grandmother, Yabby You, everybody, and no disrespect to Errol Brown, but he was kinda put in an embarrassing position as chief [engineer at Tuff Gong]. As they say, sometimes the best place to hide something is right under somebody’s nose. It was right there all the while. “Click” monitor mode. Click “channel line” position. Click, click, click different positions. You want to do a dub mix? Click, click, click. Well the dub mix is something different. Because I’m an electronics engineer, I know how to manage a console.

In your opinion, who are some of the labels, and sound engineers, and others who are producing the cutting edged dub tracks in the world today? [And] where are they based?

To be honest, I’m the worst person with names, but they’re all based right now in the U.K. They’re taking it and they’re supporting it more than even Jamaica.

In a Facebook post [on June 25, 2013, you wrote]: “The current state of technology in the now familiar “digital world” has made it the perfect time to create a new mixing tool specifically suited to the needs of dub and other remix genres. It’s called the ‘Dub Control Mixer.’” Further you wrote, “I’m exploring collaborations with pro-audio manufacturing companies in the design of the new dub control [mixer].” Were you ever able to produce and bring to market the “Dub Control Mixer”?

Well here’s what: By the time you get your cell phone, it goes through so much different reviews [and upgrades] that you don’t see it. Because I build it, not good enough. I build it, not good enough. And now I am at, what do you call it, the “final stages.”

So you are still building it?

A: Yeah. [It’s just] the technology keeps changing.

Another person on [Twitter], Jadesignlovin’ (@jadesignlovin’), wanted me to ask you if you’ll soon be developing a line of electronics, such as amplifiers (and noted that this question was based on something he understood you to have told [famous dub poet] Mutaburuka in a radio interview during the last year or so)?

Yes, right when I was leaving to meet with you I was finishing up a circuit board. And the digital technology, it just keeps changing. But at this point, I think I’m at my final design.

So we might see it [on the market] in 2019?

Yeah. Because I have a couple of people that have been patiently waiting. I need to do it, I need to finish it, and the good thing about it [is] when I need to update it, I can update it over the internet.

Nice.

You see, the old electronics, you want a noise gate, that’s a separate circuit. You want a whatever, that’s a separate circuit. The new electronics, you basically have an input and an output circuitry, and it’s whatever you upload into the chip. So I have to study the digital language –

I don’t know how you do all that, that is amazing!

Yeah. That’s what I’ve been doing, and it’s like pulling teeth out of your head.

Two more questions about equipment, and especially for the people who might read this who are “gear heads.” First, in an interview you did with “Space Bomb” records, you talked about how since moving to the U.S., in addition to continuing to create great dub music, you’ve also maintained a business creating mixing boards, amplifiers, and other personalized sound processing equipment. Putting aside the “Dub Mix Controller,” which maybe we’ll see in 2019, are you still doing personalized electronic work for people?

Not so much, no. I’m mostly concentrating – like I did a “Master Class.” Showing some engineering technique –

Yeah, you talked a little bit [in your recent interview] with DJ 745 about that.

I’m getting ready to go back to the U.K. again. So that’s where my head is right now, and I need to finish up this digital electronic stuff that I’m doing.

[In that same Space Bomb interview you did,] you said that often you would get home from a club, and your day [and night] would continue because you’d still [have to get] on the phone with China to get circuit boards. Are you still having to do that?

Well here’s what: If I don’t agree with Trump [on] anything else –

Has [Trump’s] trade war affected your ability to get circuit boards from China?

Well here’s what: The U.S. is a very good place. I would rather to be able to do it right in my backyard.

To buy the circuit boards in the U.S.?

Yes. But, to stay in business you have to have this enormous cost, which forces you to go overseas. So I and Trump agree with those things –

Forcing China to be fairer on trade?

Yes, because they can sell their cars over here, but we can’t sell our cars over there.

Since you mentioned one thing you agree [upon] with Trump, is there anything you want to say [in this interview] about the things you do not agree with Trump [about]?

Well, let me say this, I came to the United States in 1985 and not one policeman [has] asked me what my name is. I’ve been into all kinds of neighborhoods. I used to live in Woodstock. Not one police officer [ever] asked me what my name is. And I hear, “you’re getting targeted because you’re black.” Okay, why did the police stop you? You’re driving 60 miles an hour in a 25-mile-an-hour zone. That never happened to me, not one time. You have some people that come, and they come with destruction.

Come to the U.S. you mean?

Yes. They a-come with their destruction. They break the laws, dem create problems. So my thing is, if it’s a person [and] they’re going to school, they have their kids in school –

The Dreamers?

The Dreamers. They don’t have any criminal record. [And even if] they commit a crime, everybody make[s] mistakes. If it’s not a repeated felony – felonies should be looked at differently. I firmly agree that someone who goes through the correctional system, come[s] out, [and] continues to be in the correctional system, then that punishment is appropriate because you don’t learn your lesson.

Do you have any particular feelings about the release of reggae star Buju Banton, recently, from having served a lengthy prison sentence in the U.S. for a drug conspiracy case? Recently, he received a hero’s welcome in Jamaica, and there were many different feelings about this. Did you have any particular thoughts about Buju Banton’s release? And further, do you have any desire, or if given the opportunity, would you do any work [in the future] with Buju Banton? Why or Why not?

Well, everybody’s entitled to a mistake. He probably got caught up. [And it is] kinda screwed up the way the laws are in America and the rest of the world. With certain convictions. When you become an artist – and you, as an attorney, you also know this, you have to pass the bar, but you also have to pass a moral test.

True.

When you become an artist, you [equally] have a moral responsibility. Because a lot of people now start to listen to you. So what I want Buju to do, is to use his moral responsibilities and try to deter others so that they don’t get caught up in the same trap that he may have gotten caught up in.

Part of the controversy surrounding Buju Banton is not just of course the prison sentence [he received, and conviction in the U.S.], but also has to do with previous lyrics of his and songs like “Boom Bye Bye” that some people have said have increased the homophobia that exists in Jamaica. And so that is part of the controversy surrounding Buju Banton. He has renounced [any homophobic views] publicly I believe, and he signed onto an agreement that he was no longer going to use lyrics that disparage gay people. Do you feel that, going forward, Buju Banton has any responsibility with his music to counterbalance any of the negative impact of the homophobia in some of his [earlier] material?

Well, yes. Here’s what: [If] [a]nyone of us has an emergency situation, you don’t know what the doctor or what the caregiver’s personal [sexual] preference [or identity]. And that might be the same person to save your life. Inciting violence is not a good thing. Because you can’t have two set[s] of rules – because “boom bye bye on a batty bwoy’s head,” you have to treat it as a homicide. So you can’t incite violence. I know it’s a catchy sound, but at the end of the day if a gay person is throwing you a rope, and you’re drowning –

You’re gonna catch that rope.

You’re gonna catch that rope.

Now we were talking about equipment, and we got a little sidetracked. And there’s still one equipment [question] I want to make sure I ask you [on behalf of Twitter user] Dominic Ali: “What are your favorite pieces of music-making equipment?”

I can tell you the ones I’m not fond of anymore: [anything] analog. There’s no fun anything [in analog]. A digital desk does it all.

What are some of the ways that your approach to mixing and creating dub music – in terms of miking instruments, the separation of instruments, the use of effects, working with singers and musicians, touring or giving performances – how has any of that changed or matured over time [for you]?

After a while it becomes automatic. It’s like I can now do it in my sleep. But make no mistake, dub is just the performance, the engineering technique that enhance[s] the dub comes first, like the proper tonation and balancing of the instruments. That comes first. Then dub is just the musical performance.

Before I forget, DJ Selecta Jerry in New Jersey wanted me to ask you: what are a few of the very best albums that everyone who loves dub music should have in their collection? And please, there’s no need for modesty.

I would say [King Tubby’s] “Roots of Dub.” There was one by Errol Thompson and Joe Gibbs that I grew up on, I think it was “African Dub.” And there have been a few from Studio One. But I would tell everybody to get “Roots of Dub.”

After interviewing you for his book on dub music, [Professor] Michael Veal concluded: “Using the mixing board as an instrument of spontaneous composition and improvisation, the effectiveness of the dub mix results from the engineer’s ability to de-construct and reconstruct a song’s original architecture while increasing the overall power of the performance through a dynamic of surprise and delayed gratification. The engineer continually tantalizes the listener with glimpses of what they are familiar with, only to keep them out of reach, out of completion.” Do you agree with this characterization of dub music by Professor Veal?

There’s an art to it. Where you get the person hooked to a certain sequence. And then you keep switching them. And then I develop a technique that – one of the reasons it surpasses the original music is – you never hear it the same way twice.

When it’s performed or you mean whenever you hear it?

Whenever you mix it. If you even record a live performance and you play it back. To the listener, it’s never the same way twice [when] you hear it.

You hear different things in the music every time?

Yeah.

Before you work on a dub version of an album, for example, when you collaborated with Hempress Sativa on the very, very fabulous release, “Scientist Meets Hempress Sativa in Dub,” how much time do you first spend listening to the artist’s non-dub tracks, to familiarize yourself with their music, in order to be able to better manipulate the mix?

No time. Here’s what, to every dub album out there, there’s an “A” side. For example, Barrington Levy. “A” side. And then most of those albums back in the day, they were completed in three or four hours time. So a young up and coming producer like Henry “Junjo” Lawes, that we all were helping, who didn’t really have any money, so we give them an hour or two hours [of] studio time. And guess what? We have to mix the whole album in two hours. And if you talk to Flabba, a lot of times we were just helping out those producers. ‘Cause they didn’t have any money or was not financially capable. Like, for example, “Cocoa Tea.” And they make up the songs. We’d have to record them right there on the spot. And they’d only have two hours total to do the whole record. Because that’s the only money they could afford. So it [wasn’t] a whole lot of back and forth. You have to learn the songs right there and then.

There was a lot of celebration in Jamaica due to the recent announcement that reggae music had been added to the United Nation’s Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) list of cultural treasures that must be safeguarded. There were a lot of government officials [in Jamaica] who took to social media and other [platforms] to [celebrate] this news about reggae music, highlighting the fact that this happened. Did you have any particular feelings or reactions about either UNESCO’s announcement, or any thoughts or feelings about the reaction by government officials in Jamaica, who, at least in my own personal opinion, have not done enough to support [reggae] music and musicians financially, or actually, in any way. Any thoughts [about this]?

Yes, I agree with you. The government needs to do more in preserving reggae music. There are three things that bring notice to Jamaica: Rasta, marijuana, and reggae. It’s a disgrace to see an artist like Junior Byles lying in a trash heap.

There was a YouTube clip about that circulating recently.

Yes. It’s a disgrace. King Tubby’s console should have never left Jamaica. The Jamaican government should have preserved it.

I heard you talking about that [in your interview] with DJ 745. And this has always been something that has bothered me, and that I’ve asked numerous reggae [artists] about, [this] lack of financial support for reggae music [by the Jamaican government]. And a lot of [different things] have come up in the conversation, including the fact that reggae music has always been Rasta music. And that Rastas in Jamaican society have a long history of being looked down upon. Only recently are they starting to get some [real respect]. And also, not just Rasta, but that it’s poor people’s music. That downtown and uptown [divide]. I often think about reggae star Etana’s song “Wrong Address” [when I have this conversation now]. Because that song explains so much for me in terms of the lack of support [for reggae artists]. And it’s confusing to me, because as you said, [reggae music] is what Jamaica is [best] known for. [Jamaica] could make so much [more] profit [from it]. So even if [in Jamaica’s] soul, this is not [what you love], which I find hard to believe, because as Protoje and other reggae stars have told me, even if they don’t say they love reggae music in Jamaica, behind closed doors they’re dancing to Bob Marley.

Yes. Well, here’s what: Jamaican reggae music [is] the voice of the oppression and colonialism, and injustice. Make no mistake: without dub and reggae, you wouldn’t have all these sub-genres [of music]. There wasn’t any way for speaker manufacturers or amplifier builders to end-test the result of their equipment without reggae.

Mr. Brown, I know that you’re gonna be back in the U.K. next year. You have a number of shows lined up with “Mad Professor” [at the Jazz Café]. Are there any other projects or any other endeavors of yours that you’d like all of your many fans around the world to know about and watch out for?

Yes. Right now my head is at electronics. When I go back to the U.K. next year, I’m gonna be conducting some more “Master Classes.” Like we did in Liverpool. And in Brazil. It was very successful. It shed light on a lot of things, and a lot of misconceptions that people had. So that’s where my head is right now.

Can you describe what these “Master Classes” are?

Well, for example –

– What I imagine is like a conference where you teach people what you know about dub music.

Well it’s not dub music. Remember, dub music is just the performance –

– the performance. The electronics piece [I mean,] I’m sorry.

Yeah. Proper mixing techniques. One of the bad things that’s been going on since the 1960s is the guitar amplifiers on stage.

What about them?

[They’ve] caused so much problems.

Because they – they go on fire? Or what?

No. You have the main speakers. The keyboard player’s been trained – I don’t know who came up with that nonsense – the keyboard should only have keyboard alone in his monitor. And the drummer should only have drums in his monitor. Here’s what happened: There’s a calculation that’s used in electronics to calculate to put sound in phase. Especially on a big stage. The time that the guitar or the keyboard take[s] to reach the drummer. And then the sound engineer up front, he’s hearing all this different phase shift. Plus he’s hearing what’s coming through –

– You said “phase shift”?

“Phase shift,” yeah, that’s an electronic term. Even though it may be 10 milliseconds out, so when you have the keyboard, the drums and all these things picking up on a different monitor, it confuses the house mix. So especially in the Jazz Café [shows in the U.K. with Mad Professor], I’m gonna be showing why not to do it.

Cool.

‘Cause here’s what: you have the guitar amplifier on stage, the engineer at front house position, he can’t accurately tell what’s coming through the guitar amplifier from what’s coming out of the house [amplifier]. Because one of them [is] always going seconds behind, milliseconds behind. So I’m gonna be teaching more on that like I did in Brazil. Waiting on some editing to get done. And you’ll see some stuff that’s talked about for the first time. Like I say, I don’t know why this profession choose me. It choose me more than how I choose it. And thank Almighty God for life.

PART3

Geetings Scientist, great to see you again!

Great to see you too, Stephen.

Scientist, at the end of last year, the first time we ever met, you called legendary singer, producer, sound engineer, and your close friend, Pat Kelly, on the phone in Jamaica. We were talking and all of a sudden you picked up the phone – as we were talking about King Tubby and the relationships between the sound engineers that worked for Tubby – and you called Pat. You handed me the phone briefly, and I was so nervous and also excited to be speaking with Pat Kelly! [But] he was so cool and down to earth [when we talked on the phone.] Sadly, of course, I’m reminding you of this because Pat died about two weeks ago following complications from kidney disease. So I wanted to start [our] discussion today by offering my condolences; I know Pat was a good friend of yours, that you knew [each other] for a [very] long time. Do you remember how you first met Pat Kelly?

Yes, the first place I met Pat Kelly was [at] King Tubby’s studio. He used to do a lot of mixing with Bunny Lee. I had the keys to the studio, so I used to stay until the time that Pat and Bunny Lee

Roughly how old were you when you met Pat?

About seventeen.

Did you become friends right away, or did it take some time for the friendship to develop?

I would say I became friends with him right away.

Was there something [where] you could tell you guys were of the same mind and were going to be friends? Was there something between you, or just the understanding of the music? Or what was it?

Well, let me say it this way, most people they feel threatened of their job. Pat – I didn’t get that energy from him. Because Pat would mix the “A” sides for Bunny Lee, and then Pat would allow me to mix the dub sides. And you know, it went on for weeks and months and he never [felt] threatened. If I tried to [do] the same thing with somebody else, they want to do it all because they [would] feel threatened.

Was Pat [working] with Tubby before you?

Yes.

For how much longer was Pat [working] with Tubby before you [started working there]?

At least a couple of years. [But] [h]e wasn’t “working there” at the time; [he] used to come there to do work for Bunny Lee. …And then I would record Pat Kelly and some of the Bunny Lee [tracks].

What albums or songs, if any, did you and Pat collaborate on together if you know?

The list is long. The artists [included] Ken Boothe, Alton Ellis, Delroy Wilson, Johnny Clarke, and [many other] artists.

So you guys would be in the studio engineering together on those artists’ records, mixing together?

Yes. At Tubby’s. And then when Pat Kelly would come with Bunny Lee to Channel One studio, I would do the recording and Pat used to be there as a singer. Being around Pat Kelly, I never felt negative energy from him. Everybody else, they [felt] that their job was threatened [by my presence in the studio]. Not with [Pat].

When it comes to music, what do you think Pat Kelly will be most remembered for?

Well he [had] a unique voice. The man did him thing. And one of the unfair thing[s] that I spoke to [Pat Kelly’s] wife, Jackie, about yesterday [is], you have all these producers who are sitting around like vultures. When I look on[, for example,] Ebay, all of sudden a Pat Kelly record is [selling for] over one hundred dollars; it’s [exploitation].

Do you think there’ll be a way for Pat Kelly’s wife, if everyone is going to be making money off of Pat’s [incredible] legacy, for his wife to make some money, too?

Well what I told her to do is, get each and every copy [of the music comprising Pat’s discography], put them out, and re-release them. And when the [record companies and other entities] come to you and say they have a contract, you remind them that you can’t have a contract with a dead person. When the person dies, the contract also dies. And then if they try to bother her about money, it’s the wife legally who has power of attorney; they have to satisfy all the back-royalties.

Scientist, you’ve started to [speak about] this [already but], putting music aside, what kind of man was Pat Kelly?

A good person. Decent person. No bad-minded business [about him]. Not jealous. Humble. Quiet. [Could] be very deadly if he [wanted to be]. Because a lot of people don’t know that he was a martial arts expert.

I didn’t know that, wow. He did karate and stuff?

Yeah. Black belt.

But I’ve seen people get up into his face, and he just laughed it off –

[He was a] cool cucumber?

Very cool.

Before switching topics, is there anything else you wanted to say about Pat Kelly – as a man, or about his music career?

Um, what I see happening with all these wicked people, it’s like they get extended life. And a person like Pat Kelly who [was] just so humble. So mild, so well composed –

[Dies] too young?

Yeah and leaves all these fucking assholes around.

Makes you wonder why?

Well, hear the conclusion. I hope that there is something better than this messed up planet we live on named earth.

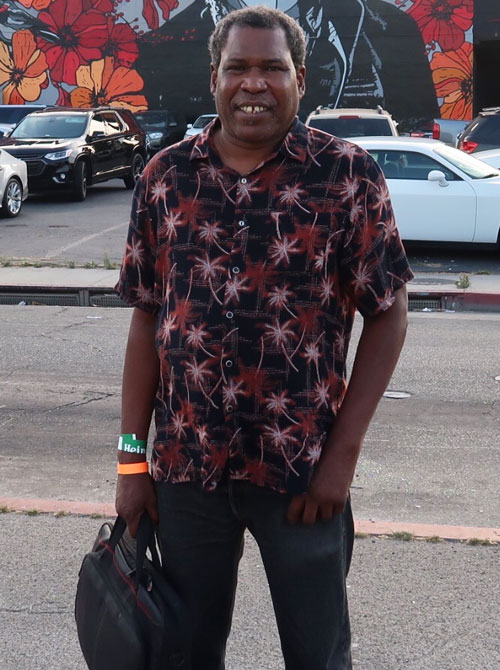

On a happier note, what brings us together today, to move on from the somberness of Pat’s passing, is the promise of a very joyful evening: You’re perform[ing] tonight at the Dub Club in L.A. with Hempress Sativa. Before getting into some of the details concerning tonight’s show, and your work with Hempress Sativa on her debut album, and [then] on her dub album, how did the connection between you[rself] and Hempress happen – how did you first link up?

Her husband and I became good friends.

This is Chris “Conquering Lion”?

Yeah.

And how did you become good friends with him?

He asked me to come and mix some [songs] for [Hempress Sativa]. And I’m a very good judge of character. He explained to me, “we’re not really a record company,” and I acknowledged that both [he and Hempress Sativa] are just starting out [in the music business]. So I just did it for them.

Given your undisputed status as a legendary sound engineer, you have the luxury of picking and choosing who it is you work with. What was it about Hempress Sativa as a singer, artist, and person that made you want to work with her?

Well I know her father real good. And I don’t know if you know that album I sent you, “Jamaica, Jamaica” [with] Brigadier Jerry?

Yes.

That’s [Hempress Sativa’s] father playing drums on that album.

Oh I didn’t realize that at all, I’m so happy you told me.

And he was the primary selector for the “Jah Love” sound system that Brigadier Jerry [would perform on]? Yeah. Every Friday evening, they would come, and I would cut dub plates. And then I recorded that album that he played drums on, “Jamaica, Jamaica.”

What do you think of Hempress Sativa’s potential as a singer as her career continues?

She has a very good potential. She’s speaking the truth through her lyrics even though some people might take offense. But as Bob [Marley] says, “Who the cap fit, let them wear it.” Because here’s what, music, and like with someone like Bob Marley and reggae, it helped to open up a lot of people’s eyes. And it helped to overturn some of the injustices.

Truth and rights?

Yeah.Respect. It’s often been observed that the reggae music business is particularly tough for female artists. Do you have any thoughts about this, and what do you think Hempress Sativa needs to focus on, or to try to improve [on], to really break it big in music?

(Laughing) Well, damn. It’s not just only music. Because right here in the United States, you have women and men doing the exact same job and [they’re] not [getting] paid the same. And when it comes to a woman, especially to have any part in the music business, it’s like carrying tuna to a shark tank.

I have a few specific questions concerning your dub album with Hempress Sativa, your process when dubbing, and [the] choices you made, but first, before teaming up on the dub album, you were involved in the mixing of Hempress’s debut 2017 album, “Unconquerebel,” true?

Yes.

Did you mix that entire debut album, or just some of the tracks?

[There are] [a]bout two tracks on it I didn’t mix. But the bulk of the album, yes.

Before getting into your dub album with Hempress Sativa, which I think was released about six months on the heels of [her] debut album, could you talk briefly about your process for mixing the tracks on [Hempress’s] debut album? Was your process for mixing tracks on Hempress Sativa’s debut album the same as you use for any artist you work with? [Another way of asking this is,] does your style, your way of mixing an album ever change depending on the artist you’re working with?

Well you were in the studio with me when I was recording Sly and Robbie [earlier this year].

(Smiling) Yes.

The first, most important part of it is the recording, not the mixing. That is where a lot of people get sidetracked. The dub? That’s just the performance. It’s like if someone asked you to paint a lovely scenery, but the canvas that your gonna paint on is dirty.

Which is why you’ve always emphasized when we’ve been together, and I’m sure at the sound check later today I’ll see, how important it is that the microphones and [all the technological equipment] is capturing the sound as perfectly as it can. Because it’s the recording that will last forever. Well, yeah, the recording is what defines and highlights everything else.

Because after that you’ll be manipulating the recording, so the recording is the original thing, the artwork that’s created in the studio by the artists that you will then, you, as the dubber, or mixer, later, will manipulate?

Well it’s easier. [Because] [f]ixing while you’re mixing only uses up a bunch of studio time. The better the recording, the better the mix. And the better the sound. You want the kick drum to be as fat as it can be. Look [at] it this way. If somebody in Africa finds a diamond, that diamond is worthless until it gets polished. So you have to polish the diamond to bring out the brilliance. But a lot of people believe you [can] record sloppy and just dub. No. The first thing, like what you witnessed there with Sly and Robbie, the recording process has to be right first.

I listened closely to Hempress Sativa’s debut album and compared those tracks to the ones on the dub album, and as a result, I have a few questions that may help shed some light and demystify what your process is when you’re dubbing a song. [Because] when I’m in the studio watching you, sometimes some of the things that you’re doing go way over my head. I can see you with the instruments, but I don’t really know what you’re doing. I know it sounds good to my ears. So this is why I want to ask you a few questions about the sounds I’m hearing [when you dub an album]. One thing that drew my attention about “Revolution Dub,” the dub for the first track on Unconquerebel (called “Revolution”), is a crank-like percussion sound. And I want to play it for you (playing “Revolution Dub”). You hear that sound?

Yeah.

This same cranking percussion sound is heard only at the very beginning of the non-dub version of the song, but you can hear it used throughout in the dub version. What is that instrument that’s making that cranking sound?

That scraping sound, it’s a percussion [instrument]; [it’s called a] güiro.

Is the use of that cranking percussion-type instrument a common technique [to use] when dubbing?

No, that’s just a percussion sound that the musicians choose to play.

But you chose as the dubber, to bring that cranking sound in [more to the song; to highlight it].When you’re doing dub, you use certain instruments to capture the person listening. And then, if you notice, it disappears out of the music. So you lead them on a different journey.

Whenever I’m [listening] to your music I go out to space.

Yeah.

But what I’m trying to understand is, how is it as the guy that created this dub (“Revolution Dub” by Hempress Sativa), [how did you think], you know what, I’m gonna add more of that cran[king] [percussion] sound. How did that come to you? Is it just intuitive?

Here’s another the thing about dub. You have to also know the music. Like when you noticed I was working with [keyboardist] [Michael] Hyde in the studio, when I was working on [those tracks for] Sublime, you have to know the music. Your ears have to be musically trained to know when the musicians are playing incorrect chords. So that’s the first thing, you have to also know the music. It’s not [like] you’re gonna dub [successfully] [without] any sense of what the musicians sound like; you don’t know anything about music.

That cranking sound – the reason why it [came] to my attention [is] I realized that that was [an element] of the song, the dub version, [that makes it] kind of addictive.

That’s what tells you. It’s how you feature it. You have to feature it at a certain spot so it’s not clashing with the other instruments. You use it – okay, the first time I smoked weed; most people smoke weed – they always trying to get back the same high, right? So it’s like the hook is the stuff that gets you started. Like the appetizer. You’re gonna have a meal, so you want something to build your appetite. So you use that to build an appetite, and after the person’s taste buds gets [warmed] up, then you give them the main-course meal.

You only hear the güiro in the very beginning of the [non-dub] version of the song “Revolution.”

Dub is like writing music; it’s a new musical composition.

In the dub version of Hempress Sativa’s song “Skin Teeth,” modeled off of the Horace Andy classic, most of the lyrics are dropped out, and then, there is another percussion-type sound which seems to be reverberated throughout the track, or maybe echoing. Can you identify that sound for me? (Playing song.)

That’s just adding delay on the guitar. [You] get “echo one” to chase “echo two.”

Ok, pause for a second.

And that’s not a percussion sound, that’s a keyboard sound. It’s a piano. Part of the rhythm section.

And you said something about “echo one” chasing “echo two?”

The reason it sounds like that is because you get echo one to chase echo two. You know, like something running after something [else].

[I’m] imagin[ing] a Pac-Man.

Yeah. You have musical hieroglyphics. In musical hieroglyphics, that’s a “dog chasing the cat.”

[And] is that sound or sound effect [being used there in the track]?

[That’s a] [s]ound effect. And the reason why it came out like that is because echo one was chasing echo two; in musical hieroglyphics, the dog [was] chasing the cat. So if I [said] to [King] Tubby, “I’m gonna make the dog chase the cat, a lot of people would be like “What the hell is he talking about?”

But [King Tubby] would know?

He would know. Because we developed certain language [to communicate with one another in the studio]. If I say[, for example,] “The angel’s wings fly over the cliff,” he’d know what I [was] talking about. If I say, “Hey, how about the high-hat chase the woodpecker –”

By the way, is that a common dubbing technique – to do that with that sound? To use that [echo one chasing echo two] sound? Because again, when I listened to it [closely], I was trying to figure out what was it in the song where, suddenly, I [felt like I had journeyed] to space. So that [is] one of those times.

Here’s what, as I said before, we have all been programmed. I didn’t choose it, it chose me. And fortunately for me, I’m the only person who has certain knowledge [about dub and sound engineering generally]. People [have] tried to do it for twenty years, tried to figure it out . . . . (shrugging).

I also want to ask about your killer dub of [Hempress Sativa’s] massive track “Wah Da Da Deng,” which you call the “Boom Dub.” To me, this might be the most wicked cut on the dub album. That dub is almost entirely instrumental. You dropped out all of the lyrics in that song except for (1) a [short] intro “In comes the unconquerebel, your highness, Hempress Sativa, the lyrical machine. When the lioness roars, no dog barks”; and (2) one [short] verse which you hear with about 50 seconds left in the song: “Hempress Sativa pan di mic, and a-go rip it up again.” It’s just a wicked dub. Out of all the lyrics that you could have chosen from the original song to splice into the dub version, how and why did you decide on [using those small snippets from the original song]?

The punchline[s]. That’s what’s gonna resonate in people’s head[s].

In Round 2 of our continuing interview, I asked how much time you spent listening to an artist’s work like with Hempress Sativa, in order to dub their music or mix it. And I think a lot of people were surprised though when they read [in our] “Round 2” interview when you said you didn’t really listen ahead of time to what an artist has done before coming to work with you. That you don’t need to go and listen [to all their work]. [I know I was.] I would envision you really having to sit there and focus, and listen to Hempress Sativa’s song like “Wah Da Da Deng” a whole heap of times before you could decide [how to mix it – and make choices like what lyrics to use, and which to drop out, when making a dub.] But when we met last time, you said, this just isn’t the case. Can you possibly say just a bit more how, when dubbing, you make the great artistic and creative choices you do – like you did for “Wah Da Da Deng” – about what lyrics to retain in a dub, and maybe accentuate/highlight?

You have to anticipate what the musician is going to do next. And then when you’re setting up the console, and we’re mixing the “A” side and getting the song ready, you have to start to memorize the song at that time. You have to have photographic memory. Once I hear a song one time, I remember every part [of the song] forever. [Now,] [f]irst, before you mix any song, you have to get the levels right. You have to get the correct tone. And then, after [learning] the [entire] song, you have to anticipate what the musicians are going to play next. Like when I listen to [legendary] [drummer] Sly [Dunbar] play, I know where he’s gonna play every roll. I know what [he’s] gonna do before he does it. You have musical anticipation where certain things play in codes.

I say time is of the essence because, of course, after a fairly lengthy hiatus from the Dub Club in Los Angeles, you’ll be back in the house tonight to do the live mixing for Hempress Sativa’s scheduled show. Do you remember what show it was you last mixed at the Dub Club?

Michael Prophet’s last show there [on October 4, 2017].

How come it’s been such a long time since you’ve done a show at the Dub Club?

Well I don’t like to wear out my welcome.

But Scientist, your face [would be] on the “Mount Rushmore of Dub” if they had one. So you’re welcome every single time you walk into the Dub Club. How could that not be?

Well if you eat the same thing every day that’s delicious, after a while it doesn’t taste good anymore. If you keep smoking the same weed every day, after a while –

You have to switch up the strain? (laughing)

(Laughing) Yeah.

Makes a lot of sense. Scientist, what are some of the challenges of mixing a live show at the Dub Club?

Having the proper sound system. Getting people to break out of their orthodox way of how they want to do [things].

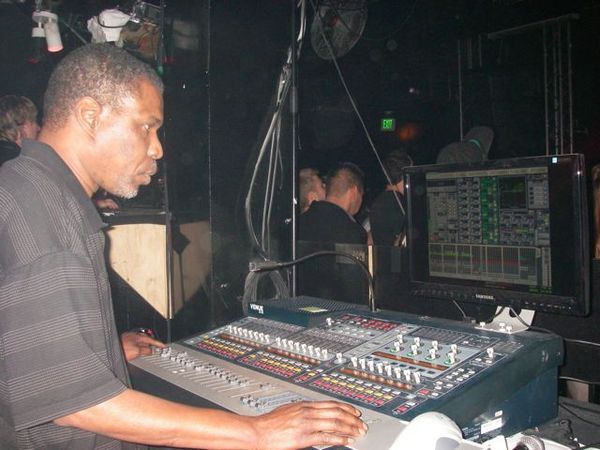

Tonight, when you are in the sound booth during Hempress Sativa’s show, can you describe a bit what you’ll be doing with the controls? And how does mixing a live show and what you’re doing with the control board differ than when you’re mixing in a studio?

Ok I want to give you an analogy. One is swimming into a swimming pool, and one is swimming in the Atlantic Ocean with twenty-foot waves. Because the studio is a controlled environment; [a] live [show] is uncontrolled.

Now we have to wrap this interview up so you can get to the sound check, so: Can you talk a bit about the importance of the sound check and, as an engineer, can you describe how the sound check is done?

Well, yeah. The first thing is that the biggest enemy is the guitar amplifiers. Because the standard way that the guitar amplifier gets set up fools the [sound] engineer. And this is why you can see the biggest, [most famous] artists onstage [at shows] playing stuff, and you can’t hear it. Because the monitor and the guitar amplifier is giving the engineer a false perspective of what the music really is.

Scientist, thanks so much for this time and special window into your work. I wish you tremendous success with tonight’s show!

Thank you.