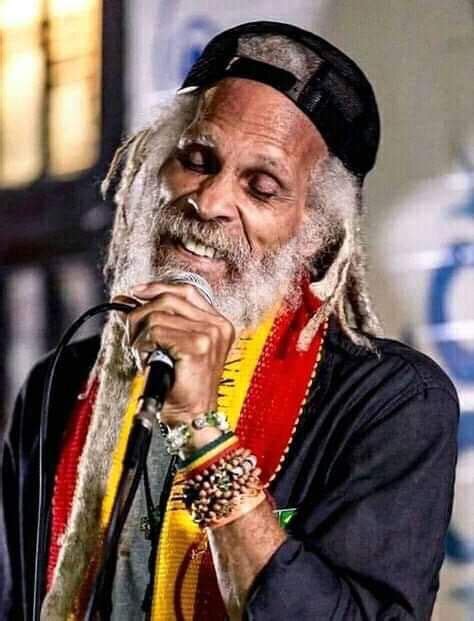

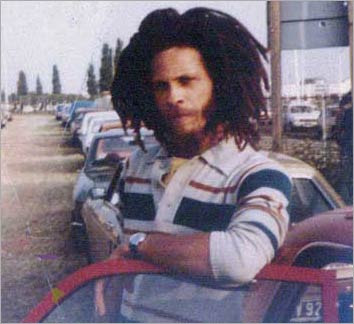

Cedric Constantine Myton (born 1947) is a Jamaican Rastafari reggae musician who was a founding member of the roots reggae band The Congos.

Myton was born in Old Harbour, Jamaica. He began his singing career with the group The Bell Stars, who recorded one single 45″ “over and over” (1967), which was a minor success. Alongside Lincoln Thompson, “preps” Lewis, and Devon Russell, Myton formed The Tartans in 1968, the group released many 45″ singles, and had early success in 1969 with the hit 45 “Dance All Night”. After a couple of years The Tartans disbanded, and Myton alongside Lincoln “Prince” Thompson, formed “The Royal Rasses”. Myton spent almost 3 years alongside Thompson, writing the tracks which would constitute the Royal Rasses album Humanity. Myton also sang on every track on Humanity. This album was a big success, although Myton left The Royal Rasses shortly after the release of Humanity. The band continued without Myton, who went on to form The Congos, alongside Roydel Johnson, who had a rich “tenor” and Watty Burnett who provided a “Deep Barritone”, which combined with Myton’s rich “Falsetto” anchored The Congos.

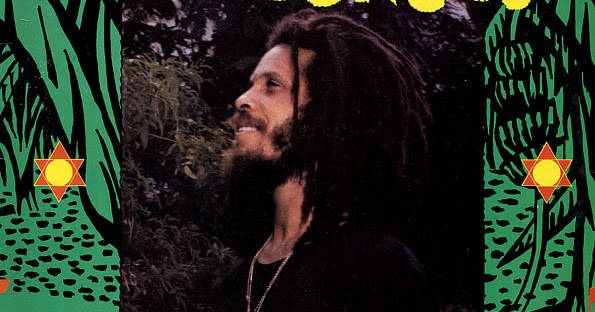

The first album they recorded, Heart of the Congos, was produced by Lee “Scratch” Perry.Due to both a dispute between the Perry and Island Records’ favouritism of Bob Marley, Heart of the Congos, was shelved because it was deemed “a strong album.” Island Records, led by Chris Blackwell, felt it would take away the limelight from Marley. Initially it was released in very limited numbers on Perry’s Black Art label and Perry re-mixed the album adding various external sounds, such as “cow horns” provided by the baritone Burnett. Many years later the English group The Beat released Heart of the Congos on their own Go-Feet label, as did the company Blood and Fire. Heart of the Congos was a big success.

Later Myton pursued a solo career. After some time, the Congos reformed and recorded an album titled, Back in the Black Ark. The group toured as well, appearing at music festivals such as the 2012 Rototom Sunsplash.

https://www.reggae-vibes.com/articles/2020/07/interview-with-cedric-myton-of-the-congos/

Interview with Cedric Myton (of The Congos)

by Peter I – 2010

Few albums in reggae’s history have made the same mark of perfection as the Congos’ epic ‘Heart of the Congos’. Produced by the inimitable Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, it is a landmark among cultural albums and defined the roots reggae genre upon its release in 1977.

The Congos themselves naturally never surpassed it, that’s for sure. The Congos was Cedric Myton’s fourth musical formation, having previously experienced success in vocal groups the Bellstars and The Tartans. He also became a member of the Royal Rasses, later made famous by the late Prince Lincoln Thompson. Together with Congo Ashanti Roy and Watty Burnett they cut a series of fine albums for major imprints before splitting up in the mid 1980s. The legend grew. The demand for the group’s reappearance on the scene increased, and, finally, in the 1990s they regrouped and got the definitive release of their debut album remastered and repackaged by the now defunct Blood & Fire label. The group are now touring and cutting new albums like never before.

You are the oldest of the family of Lester and Daisy Myton, and you are born in St. Catherine? Yes.

How big was the family? That time? Wow! Well, it was really eight of us, yunno, as kids. I mean, mother and father… it’s a long story.

But did you grow up in Old Harbour? Yes, I did for a time in Old Harbour bay, that is the seaport town.

What was life like there in the 1950s? Oh, beautiful, man. Beautiful. Beautiful days, those days were the good ol’ days.

In what way? In every way. I mean, as kids we got everything so we think everything was just like that. Yeah, we never knew how life was so rough, y’know, all over, but our family could provide for us. Which is very good.

What did your parents do for an income? Ah, well, they used to rear bees, make honey. So we grew up on honey. I ate a lot of honey and honeycomb then. We used to raise bees on an island we called the Goat’s Island.

That’s in St. Catherine too. Yes.

What about music in that family, what brought you into music at that time? Well, growing up I loved music, in the church. I grew up in the church. So we learn music from there and gradually we do our own t’ing.

What was some of your favourite acts back then? Well, in those days it was more like – in the young days – merengue and those kind of music then, yunno, Latin music, or church music.

So the first group you formed sometime in the mid sixties, was that the Tartans or it was the King Edwards recording group, the Bellstars? Yes. Oh yeah, well, the Bellstars was before the Tartans. Sometime I don’t even talk about it, but we go back a long time… The Bellstars was the first one and the second one was the Tartans. So the Tartans came out of the Bellstars.

Who was in the Bellstars? Ah, it was I myself, Devon Russell, a friend called Joe Sarkey – he’s living in America now, Bobby Sarkey, yunno. And there was another friend who was also a part of the Bellstars, it was Ratcho, that’s Lukie D’s father. You know Lukie D, the singer?

Yes. Yes, his father used to be in the Bellstars.

And Bobby Sarkey used to sing in that group the Immortals (cutting such wonderful, deep songs as the Pablo produced ‘Can’t Keep A Good Man Down’ in the late seventies, but shouldn’t be confused with the namesake who recorded ‘Bongo Jah’ in the late 1960’s for Joe Gibbs. Sarkey later cut solo tunes for the Wackies stable in the Bronx, NYC). Yeah, I think so. I think so, after a time.

What did you record with the Bellstars? Yeah, we did a song named ‘Over & Over’ (sings) ‘Over and over, over and ooover… ta da daa ta daa’, something like that. That melody line there.

It was ska? It was in the ska days.

Who did you record it for? Ahhhh… I had a far cousin who was a teacher. He had some money so he was kinda spending it on us.

So it was an independent release. Yes. It was independent, yes.

Did it sell? Oh yes, we had a lickle thing that went down there.

The backing group? Ah, it was good musicians. It was ‘Drumbago’ (Arkland Parks) and quite a few there, maybe Jackie Jackson (bass) I can still recall, and some other ones there. I think we had Hux Brown too, it was the name of the guitaris’ deh.

It was cut at, where? I think it was Federal. Yeah, was Federal. Or I figure it was West Indies (Recording Limited), I think it was West Indies, one o’ dem.

WIRL. Yes.

Then the group broke apart. The Tartans came out of the ‘ashes’ of the Bellstars. You had a few hits with them, the Tartans? Yeah, yeah, well, we had a few hits. Up to now I have an album which is not released, of the Tartans.

That group recorded quite a few singles, so there should be enough for an album. Good to hear. Yes, we did quite a few singles. But we are planning to release the Tartans album eventually. If it’s not even this year maybe it’ll be next year. The Tartans stuff is still in the can.

Should be great, definitely. There’s at least a dozen rare 45’s to make use of. Yeah man, I have them. And we did two for Duke Reid too at the time, ‘Far Beyond The Sun’ was one of them.

Right. Who made up the Tartans? Well, the Tartans consist of I myself, Prince Lincoln Thompson, Devon Russell and Lindburgh Lewis. Well, Lindburgh is still alive, he’s in America now. But as you may know Devon Russell have died. Prince Lincoln Thompson also have died.

Yes. How was the sessions with the Tartans? You recorded mostly at Federal? Yeah, Federal and some of the Tartans stuff we did down at Downbeat (Coxson) one o’ the time, down at Studio One there.

And ‘Dance All Night’ became the biggest success for the group. Oh, ‘Dance All Night’, we did it at Federal. Yeah, that was a (Ken) Khouri, Federal production.

Tell me more about that. Well, the song was a hit song. The first payment we got was £ 484 pound, then. And from that we don’t get a penny up until today (laughs).

How did you handle these conditions, not getting paid… Well, at Federal… at the same time we broke off the contrac’ with Federal, like. We feel they should’ve treated us better. So I think what happened, then, there was a deal made, like, the only way we could get out of that contract with them, they have to keep the royalties. So that was how Federal ran their show there. If we did come out of that contract with them, they’d keep the rest of the royalties, something like that.

So that was a constant argument between the two parts. Yes. Well, right now they sell out all those works. I mean, like the publishing, we never collect a penny for those publishing up to today. Yeah. So there is still so much bad policies still going on there, which needs attention. I mean, our government should really take control of the situation.

The Federal production team of Mitchell & Scott took care of those recordings? Yeah.

You still remember the instrumentalists for the Federal sessions? You mean on the ‘Dance All Night’?

Yes. Yeah, for the ‘Dance All Night’ it was Jackie Jackson, it was Gladstone Anderson that play keyboard or piano, and Leslie Butler was playing another lead piano also, on some of the tracks. And you have Drumbago was playing drums, with Jackie Jackson, bass, and Lynn Taitt was playing guitar. Lynn Taitt and Hux Brown was playing rhythm and lead guitar there.

Arranging the stuff, it was…? Well, the piano, that piano sound was created by I myself and Devon and Gladstone Anderson… (hums) ‘pa da da da pam pam pa da da’. You know (chuckles)?

It almost sounds like a merengue. Yeah, it’s a cross, it’s a cross or a bridge there.

These are the beginner days for you. What did you pick up from that experience? Yeah, well, we did start out then. But it was a learning process, y’know.

What do you feel of those recordings now, do you still like them? Oh, yeah man, yeah man. They’re antique, they’re antique. For, what happened, everyt’ing we had to do live, there was no overdub then at an early age. At this time now we use overdub, yunno, but at the first, firs’ set of recordings now it was live – everyt’ing once, one shot. Yeah man, great feeling, but you cannot make any mistake (chuckles).

But if you did… You have to start all over again.

And someone would yell their frustration at you and the group would gradually lose confidence and what not (chuckles)? Yeah, but you are so determined not to make any mistake.

The connection to Blondel Calnek, the Caltone label now, that was the next step? Oh, you mean Ken Lack?

Ken Lack, yes. Oh yeah, that was another history of the programme too, we’re going way back. We did some of the songs for Ken Lack too. (Sings) ‘Wake the town and tell everyone…’. Yeah, ‘Awake The Town’ was another song we did for Ken Lack.

And ‘Coming On Strong’. Yeah, ‘Coming On Strong’ too. Yeah man.

‘It’s All Right’, ‘Making Love’, ‘Save A Little Bread’ and ‘Solid As A Rock’ for Caltone as well. Yeah, yeah. And we have all those songs, we have them compiled for the Tartans album.

Good to know. Yeah, we have them all.

You got treated better at Caltone? Oh yes, yes. Yeah, it was a better treatment, truthfully.

How much did people like Lack take part in the production? No, that’s really financially, really. For, more time it’s just the musicians. Some of the musicians them or… all of the musicians them who work on this t’ing. And when the artist practice the song, on a whole, the musicians would work out the details. If he doesn’t have his t’ing pat down, you’d have to go and rehearse the stuff.

That sweet rock steady feel, is that something you would even incorporate and blend in the new stuff you are working on? Yeah, well, it’s the same format. It’s the same format, the same rock steady feeling. It’s the same t’ing (chuckles). It’s the same whe improvisation is concerned, or certain lickle lick.

In those days, you lived mostly around Cockburn Gardens? Yeah, Cockburn Pen.

That’s Kingston 11. How was it back then? Rough, rough. Yeah, it become rough now. Then, it wasn’t that bad then. But it become really rough right now.

How come? Ahh, up in the eighties it started get rude there. Yes, started get very rough there.

Politics.

Yeah, yeah, through the environment of… and the politicians.

What about the days when you first started to hang out with people like Prince Lincoln Thompson, how did you bump into each other? Oh, well, at the time it was… I myself and Devon who started the group, and then Lindburgh came in. Well, ah, Prince Lincoln was the youngest of all, I think he was just a youth, then. At the time he came from school he would have some rehearsal, and he was brilliant as a kid, loved to sing. So we tek him as a lickle kid under our wing, then. He had some idea, but he lacked the rest of the programme coming up. So he would become one of the pioneers in the long run too.

Did you record with him when he went to Studio One and cut tracks like ‘Daughters of Zion’, ‘Live Up To Your Name’ and ‘True Experience’? Oh no, no, no. Now and then, through I heard of Mr Dodd’s treatment towards musicians, I was… I wasn’t interested in doing any work there. Then, at that time, y’know. But then eventually I still go there and do some work, in about ’02. Yeah, in 2002 when I went back to Jamaica I did some work there, with Mr Dodd. But first thing I wasn’t interested in it because of his attitude towards these people back then, so I never worked with him. I had the treatment of my other partners in memory, yunno, like Devon Russell, he worked a lot with Mr Dodd there, lots of times.

He cut an album for Coxson too, ‘Roots Music’. Yes, more than one, and I see the treatment… Prince Lincoln also did a lot of work with Mr Dodd, and I see how he suffer around him during that time. But is only after a time when I spend all my time aroun’, I and Winston McAnuff, we buck up all over the place. So we were in Paris at the time and about to go to England, he say “I see Mr Dodd”. Anyway, he (Coxson) was up by VP Records one of the day, y’know, in the earlier times, and so I said, “Big man, any time I come back a Jamaica yu and I a go do some work, yunno”. And him say, “Yeah man, we’ll do that, Jackson! Come in, Jackson!”

(Chuckles) So when I went back to Jamaica, away from my hut I went to there, and I go an’ do… I jus’ check him out an’ ‘im say, “Yes, come in”. And I did an album, more than an album with Mr Dodd. Yes. It’s an antique work also. It’s not out, everything was done for it to be out, but he died suddenly within the process (of getting it out). And after that his wife, she abandoned the ship. Totally. She abandon the ship. She don’t want that programme to go on. I think she create the downfall of that empire. I think so. The downfall of the Studio One empire was created by the people who now controls it.

But Coxson did at least put out a 45 from those sessions. Yes. But I do have an album which I am planning to talk to dem pertaining to get back the album from them, or whatever can be done. I need that for my own collection, y’know. Personally, for my own catalogue. For, when I went back to Jamaica the other day, from America, I did quite a few albums. I did one also with Linval Thompson. And I and Joe Gibbs, with Errol T, I and Errol Thompson did an album too before he died. So when I went back I did a lot of work there. I did about twelve albums.

That much? Twelve album, really. I did another thing too. I and (Bunny) ‘Striker’ Lee, we go way back. I did quite a few works. I get some riddims from Striker Lee and I worked ‘pon them. I did about three album for Striker Lee, which is… one of them is called ‘Cock Mouth Kill Cock’, and there’s others also.

‘Cock Mouth Kill Cock’ was based on vintage rhythms. Yes, yes.

Back to the Tartans. After you decided to call it quits with the group for whatever reason, did you go and do something else in the business, or you basically got out of the music business at this point? No, not really. Well, after a time both I myself and Prince Lincoln was working, as a friend, and also Devon Russell. And so that’s how the Royal Rasses formed now.

If we’re talking like, say, from 1968 to about ’73 or ’74, during that period, that’s not exactly a period of inactivity? Yes, well, that time I myself and Lincoln were workin’ much more than Devon Russell. So, at the same time we worked with friends too, so I worked with both of them. Yeah, but more attention we pay to Lincoln at the time with the Royal Rasses. For, we were putting our money together to do the ‘Humanity’ album.

Classic. And that production were by I myself, Lincoln Thompson and you may remember Errol Thompson (of ‘Turntable Time’ fame), the DJ from JBC?

Yes, since passed (the very popular radio DJ was shot sometime back in ’83). He was a part of the financial production also. We three were doing that album, the ‘Humanity’ album.

You sing on most of the tracks on that LP? Yeah, all the tracks, all the tracks on the ‘Humanity’ album. Yeah, that album were by I myself and Lincoln. We worked on those songs for at least two, three years before that album was released.

You had some other Rasses in those days, like Johnny Kool, Junior Peterkin? He was a friend, doing background vocal, yunno. And another one they called ‘Cap’, another friend also. We kinda learn them the ropes, so far (chuckles). Or try teach them the t’ing, background.

Did it work out? Oh yes, but it was very hard. It was extremely hard but it worked.

And it turned out to be a boost for the album in landing a contract with the Ballistic/United Artists label at the time, in the UK. Yes, yes, that was a very good deal with them. But that was the downfall of the Royal Rasses for me.

Why? Ah, well, at the time when Lincoln had gotten the advance I didn’t get a penny out of it. All, everything, Lincoln Thompson escaped with all the money. And I think he received about £ 1700 pounds, then. It could’ve been more, but that’s about what I’ve heard so far.

That’s a neat little sum… Yes, he bought a house and a car and many other things, and I invest all this time in the work with him as a youth. His remarks was ‘the earth’s open’ and give him this ting, before him give me a penny. That’s what he said. And at the same time when the United Artists called for him for a tour, he come to me to tour with them. And I tell him no, I can’t do that. So there and then I and Ashanti Roy work, I knew Ashanti Roy by then. The Congos create within that period now.

How did you link up with Roy? Well, when we used to go to Nyahbingi, sometime I used to see him come to the Nyahbingi Church. And sometime I tek Ras Michael and he was there sometime too. That was the Nyahbingi time, yunno.

What was Roy’s experience in the business up to that point? I think he was learnin’, he was in a creative phase so far. Yeah. You know, he was in a creative phase, learnin’ ’bout the music.

You used to write songs for people before the Congos came about, didn’t you? Well, I always write songs. Even from the Royal Rasses period. Most of the songs on the Royal Rasses album, it was really Prince Lincoln who was the master writer, then, on those songs. I feel the trend it was taking, overall. During the time, across the channel, I’ve seen the road he was directing himself and the whole programme, the whole world around his programme, so I say, ‘if that’s the way’… You can read between the lines, so you know what to expect.

So you and Roy had an arsenal of new material by the time you hooked up with Perry. What was the connection to him before this? Ah, yeah, I know Perry for quite a while. You know, from our younger childhood days, I know Perry. Meanwhile, amongst the music an’ t’ing, he know Mr Dodd an’ all those things. So Perry used to work with Mr Dodd up by the studio there, until he finds his way and make his own studio. And then he’s getting a name by recording with Bob Marley and many more. So eventually – we know him, I know him, and Ashanti was more affiliated with him more than I, then. But I knew him also, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry. So anyway, we go over there one day and he was glad to see us and I show him seh we had some works to be done. Him seh “Come in now. Anytime we can work”, so we just go in the studio. Some of the songs were written right there, on the spot there. Songs like, mainly, ‘Ark of the Covenant’ was written right there. But he was the one that give us the idea still, I just sang of ‘the ark’. So right there and then I just wrote that song the same day, make the song and finish it, the song about the ark. But one of the first songs was really ‘Solid Foundation’, that was carved out for the Congos’ work. ‘Solid Foundation’, ‘Judgement Time’ was another one, ‘Open the Gate’, ‘Congoman’ and ‘Can’t Come In’, y’know.

What was actually the original conception of the Congos as you recall this? Because I mean, to me, it always sounded so different from the ‘dancehall’ music of these times, it was several steps beyond that. OK. Well, honestly now, it was a churchical t’ing. And it wasn’t named. For even then the name of the Congos wasn’t formed as named, it was just to work within a works. So the name ‘Congos’ create’ out of the music, like ‘congo a bongo, bongoman shanti’ and, y’know, the whole atmosphere.

Spiritual vibes. Yes, it was more a spiritual t’ing. So it take unto itself, the Congos name. Very spiritual, in that fashion, yunno (chuckles). ‘Congo a bongo’, yeah.

The response in dances to these songs at the time, what was that? Oh, yeah man, the people them love it then and there, man. Oh, Jah Love used to play those songs. Yeah man. You see, it was the young yout’ of the Rasta movement also, so those songs redeemed a lot of Rasta people musically, spiritually and physically. It really lift them up, the music.

That falsetto and vocal technique you were so fond of using back then, is it difficult to maintain? Because you changed that a bit after the first album. Oh, we patterned some songs to certain atmospheres – some vibes, yunno. So ‘Fisherman’ is a different flavour from ‘Congoman’, ‘Can’t Come In’ is – it’s all different attitude, atmosphere or identification, y’know. Or even to identify the special vibes within those times. ‘Congoman’ is also from that vibe. ‘The Wrong Thing’, they have their own flavour. ‘Solid Foundation’ is a different… you know?

Finding the right pitch… Yes, so we try to carve it out like that.

And if we’re talking pitch, Perry was the one to suggest how you should approach the tracks, a recording, vocally speaking? No, no, no. I kinda try to put myself in that form, to change some of the songs, to what suited it or what suit one song more than the other. For real.

So that form of experimentation meant automatically several takes and mixes of the songs. OK. For even ‘Fisherman’, like if we do ‘Fisherman’ today, he’d go back tomorrow and do ‘Fisherman’ all over again, with a different set of musicians. So it’s a different flavour, totally.

And the line-up at the Ark was pretty impressive. There was quite a few. They were the cream of the crop. You had Ernest Ranglin (guitar), Winston Wright (keyboards), you have Boris Gardiner (bass), you had Billy (Johnson) who used to play guitar. You had Chinna Smith, you have lots of guitarists you come across. And lots of various musicians, Sly Dunbar was one also, Mikey Boo – Michael Richards, he was another drummer.

Anyone in particular who made a special mark on those recordings? Yeah, well, one of the main man on those recordings was Boris Gardiner, Winston ‘Brubeck’ (Wright), Keith Sterling, Ernest Ranglin, he play on most of the tracks also. ‘Congoman’ was Ernest, most of those songs, Ernest play along on them. Yeah.

Who was it on bass on ‘Congoman’ again? Oh, the bass on ‘Congoman’ was played by Winston Wright.

That’s it, yes. Yeah, the keyboard man, Winston ‘Brubeck’ Wright, yunno.

Did you find it comfortable to create in there? Yeah, yeah. It was a vibes thing.

I see. Well, honestly, Black Ark carried the swing, then. You understan’ (chuckles). Everyone loved Lee Perry’s ideas and loved to work with him also.

And the album, upon release, it didn’t come up to a satisfactory level, did it? In terms of sales. Well, the album didn’t take off directly, y’know. For quite a while we didn’t get any money so after a time we stopped work, for the (lack of) payment.

You got it re-released through The Beat’s Go Feet imprint in the UK. Yes, and also Blood & Fire (he then goes on to tell me about the shady dealings with VP’s release of the album, something he, perhaps as expected, didn’t get a penny from. Five of the albums on the label is lost apparently, ‘not one red cent’ has been paid, as he puts it). Within the music industry, we should have someone responsible enough to take care of these works by all those pirates! Or pirate giant, in other words, sabotaging the music industry. The artists, in other words. I myself and many, many more have things to say ’bout them.

You settled down in London in the early part of the eighties, and started to tour with The Beat. Well, when ‘Heart of the Congos’ came out, what happened, we were in England then and within those times we had a collaboration with the (English) Beat there (he appears on the Beat’s ‘Wha’ppen’ LP, adding vocals to ‘Door Of Your Heart’). Their band manager was a man called John. And my wife met John and say “Ohh, yeah, we could do some work”, with the whole Congos programme to that. The Go Feet t’ing came up. They release ‘Heart of the Congos’ on the Go Feet label. And there and then we get a deal with Arista to do an album. So there and then we did a recording and released the ‘Face the Music’ album.

That was a pretty slick production. Yes, yes, it was a poppy, poppish idea. But at least we had a syndicate that was involved with the programme, yunno.

Did you feel comfortable by the idea to water down the music in that way? No, it’s not a matter of ‘water down’, for it’s no water down in the music. You have other goals, you have other kinds of flavour, you’re having more guitarists or… you know?

What became of the relationship with The Beat? Well, we still correspond now and then, but we’re walking different steps, always. But they’re all over the place.

And then you settled down in America. Yes, in the eighties, for a little while, somewhere there. I were in America for a little while.

For several years the Congos was laid to rest, nobody knew what had happened to you and the group at that time, and I guess that’s when you lived in the States. Yeah, well, we did some form of distribution thing that – then we link up with VP, y’know, and… it never work out anyway! So we start to tour all over America. We tour in all of America, we do a lot of shows in America. Both from New York and change up to Montana to San Francisco, San Diego, all over. Portland, Oregon, we’ve been to those places.

Before I forget, (Winston) McAnuff told me that you cut some music at Chris Stanley’s Music Mountain studio in the mid 1980s. Yeah, I don’t even know what happened with those tapes up until today… those tapes are gone over the roof!

(Laughs) (Laughs) Yeah.

What was the material you worked on there? Oh man, it was some very great songs. I recorded most of those songs over back. But it was some great songs. Great ones, it was a antique work. But Chris was so hard… for there and then even EMI was to do some work with us, and Chris blew up everything. It just couldn’t work out. All I did, I just got some studio time, I pay him some studio time… and I owe him for some studio time, and he want fifty per cent of everything I’d get from EMI. So I say OK, take the rest. I left. Only McAnuff get back his tapes out of that programme there.

You haven’t done much work on digital equipment over the years. Is that something you try to avoid as much as possible, you rejected the ‘Sleng Teng’ and ‘Tempo’ craze at the time? Maybe it took over the market, but it took the music to a different level.

How did you feel about that? Personally it hurt singers like myself. We have to think of more live stuff, live backing in the work at the moment. And we’re getting a response, good response.

But you made some work on computerized rhythms. I think of your single for the Mad Professor, for example. Oh yeah, yeah. We did some work with Mad Professor, yeah man. Great. Some great work with Mad Professor.

Yes, very Ariwa… Yeah, we just laid some tracks there, really. And he have some good tracks still.

Good to hear. And he have some very good ideas also. And what he do, he get a lot of inspiration from Scratch, for some of the work there.

What about the Glimmer label, you reissued some of the vintage tracks on a 10″ some years ago, was that your label? Glimmer…?

Forgotten which tracks it was, but it was an EP as I recall.

(Long silence) So many things happen in the past there.

And speaking of dubious releases, labels like Sunfire and Jah Live had ‘Heart of the Congos’ once upon a time, with or without your consent? Yeah, but in our early days there, in France, we did a thing with Jah Live, then. With Sunfire, that wasn’t we.

And albums like the second one, ‘Congo Ashanti’, it came out on CD again (with the first CD release by VP) through a company in Germany. Yeah, called Indigo.

And it did well? Well, so far.

But the album that kicked you out there again with rave reviews was undoubtedly ‘Swinging Bridge’. Oh yes, up to now.

Who was it produced with/for? We record that album for ourselves, and we give it to Mediacom (France) to distribute it. We worked with Chinna Smith, Style Scott, Horsemouth, it’s a bunch of musicians in there, top notch musicians.

And some time before that, I believe it was ‘Revival’, a CD released through VP. You and Watty (Burnett) together. Yeah, in America.

Right. Yeah, that was also a very good album.

I remember one 45 prior to the album’s release, ‘Revival’ on your own imprint. Yeah, ‘Reggae Revival’.

Now, the Congos is a group which has gone through several phases and stages throughout your whole career as an entity, quite often with your inner group conflicts in the limelight. And naturally you wonder what is myth and what’s fact in all that. How do you feel about being the cornerstone of the group, holding it together? Sometimes it’s rough but you have to take that as well. It’s a rough job, keeping things together. Very rough.

It’s better with a trinity than a solo adventure though, right? Yeah.

How did you feel about what is probably the definitive release of ‘Heart of the Congos’, that Blood & Fire did? Yeah, they did very well, very well.

There was a solo album put out not too long ago, ‘Inna De Yard’. All acoustic. It showed you in a good light, in that element. Oh, well, ‘Inna De Yard’ is a thing that Makasound did, which is working quite fine, with we and Chinna Smith. It’s working quite well.

Is that something you could see yourself doing more of, all acoustic, unplugged? Oh yes, yes. But with our own crew. For sure.

To have a compilation, properly mastered and mixed the way it should be without tampering with the original sound, it would surely be a treat for rock steady fans as the Tartans was a fine example of this era’s vocal artistry. In your dreams it would, hopefully, trigger the Khouris to reissue more of the rock steady period at Federal studios, but it wouldn’t be something to hold your breath for. Unlikely, perhaps, in a time when the record industry is dying a slow death. As for the Congos, they teamed up with Perry once again for a French project which came out as ‘Back In the Black Ark’ (Mediacom) quite recently. They even touch a bit of Sam Cooke. Intriguing? Go check the album. With the ‘Congo Ashanti’ album already reissued the way it should be, I’m hoping the ‘Image of Africa’ album will get the same treatment one day, maybe including some dubs and what remains in the can from these sessions, if any. Perhaps we would even get the opportunity to hear Cedric’s solo project for Coxson. Time will tell, obviously.