https://www.reggae-vibes.com/articles/2021/10/sly-dunbar-the-sly-factor-interview/

Sly Dunbar: The Sly Factor (Interview)

by Ray Hurford, More Axe (1987)

As Sly will mention later on, the first record he played drums on was ‘Night Doctor’ by the Upsetters, which he credits as an Ansell Collins production. His next session was ‘Double Barrel’ by Dave & Ansell Collins, which came out in 1970, and was produced by Winston Riley. It seems he then joins the Youth Professionals, who got at least one release backing Carl Dawkins on his fine record ‘Walk A LittleProuder’ issued on Newbeat in the UK in 1971. At the time the Youth Professionals played regularly at Dickie Wong’s ‘Tit For Tat’ club on Red Hills Road. By 1973 Sly was working with Skin Flesh & Bones also at the ‘Tit For Tat’ club. In November of that year the band, with Al Brown on vocals, issued their version of Al Green’s ‘Here I Am Baby’. It was produced by Dickie Wong, and it hit big in Jamaica and the UK.

SLY DUNBAR: THE SLY FACTOR

So much so, that Trojan issued the instrumental version of the tune by the band called ‘Butter Fe Fish’ on the Harry J label in 1974, which also did well. From that time to the Rockers era, Skin Flesh& Bones were probably Jamaica’s No.2 backing band. The top position belonged to the Soul Syndicate Band, who worked with Bunny Lee on the popular ‘Flying Cymbal Sound’.

But Skin Flesh & Bones were always there with their reggae version of the Disco/Soul bump sound, and it was that sound that first gave Sly some recognition. Along with the rest of the band, who consisted of Bertram MacLean (guitar), Lloyd Parks (bass), Errol’ Nelson (organ) and Pat (conga & bongoes). During 1974/75 Skin Flesh & Bones worked with many producers. But it was Lloyd F. Campbell who probably captured the group at its best.

Working out of Randy’s Studio 17 on North Parade, he recorded with them some of Jimmy London’s best work. Music like ‘What Good Am I’ and ‘I’m Your Puppet’ and the Itals classic ‘In Dis Yah Time’. These tunes were issued by Jama in the UK, along with what many consider to be one of the best dub albums ever made, ‘Fighting Dub’. The album produced by Lloyd F. Campbell showed all that was good in Skin Flesh & Bones bump sound. It was an almost perfect integration of then current soul & reggae. However, Sly wanted to take the sound even further. And it was Joseph ‘JoJo’ Hookim, owner of the emerging Channel One studios, who gave him the opportunity. Channel One released ‘Right Time’ by the Diamonds, and the rockers sound was born.

Sly was now a member of the Revolutionaries who consisted of a combination of musicians including Sly & Barnabas on drums, Robbie Shakespeare/Lloyd Parks/Ranchie MacLean on bass, Rad Bryan/Bo Pee on rhythm guitar, Dougie & Tony Chin on lead guitar, Ansell Collins on organ, Winston Wright on piano, and on percussion were Sticky and Skully.

With the Revolutionaries, Sly played on a number of outstanding dub albums, all recorded for Channel One including ‘Well Charge – Vital Dub’ (which was so popular on pre-release that it was being sold in record shops in London for four or five times the amount of a normal prerelease album), ‘Disco Mix – Satta Dub’ and ‘Full Charge Revival Dub’. All these albums and countless singles for Channel One, and for studios like Joe Gibbs (where he played drums as a member of the Professionals) and Sonia Pottinger’s Treasure Isle studio, quickly gave him the kind of popularity where his name had to be on a dub album if you wanted it to sell.

In 1977, Derrick Harriott took the idea one step further and put Sly on the front cover! ‘Go Deh Wid Riddim’ by Sly & the Revolutionaries released on Derrick Harriott’s Crystal label was an instant success. The excitement the album generated together with the general positive aura that surrounded Sly at the time was enough for him to be wanted by Virgin’s new Front Line reggae label, and they signed him. As Sly explains he was to be found on 90% of the records coming out of Jamaica then (more like two thirds). Virgin had a very easy task to put out as good an album as Derrick Harriott’s. Instead they issued ‘Simple Sly Man’ in 1978. The album was greeted with widespread dismay. Sly was more hopeful about his next album for the Front Line label ‘Sly Wicked & Slick’ that was issued in 1979. It was certainly an improvement over ‘Simple Sly Man’, but two out of the eight tracks were very easy listening.

The response to the unfavourable reception given to his two Front Line albums was ‘Disco Dub’ released in Jamaica on the Gorgon label in 1979. The album represented two things: the breakup of the Revolutionaries (Channel One’s studio band was now the Roots Radics) and the beginning

of Sly’s partnership with Robbie Shakespeare. The two of them began to produce Black Uhuru. But their first album together as ‘Sly & Robbie’ was ‘Disco Dub’. It’s an exciting album. It brings together the Revolutionaries, again, but this time they are now being arranged & produced by Sly & Robbie. Ranchie, Winston Wright, Ansell Collins & Dougie responded very well to the change.

They gave Sly & Robbie the good start they needed in the business. ‘Disco Dub’ showed that Sly & Robbie had some good ideas. They wanted to go forward, but had enough sense to know they couldn’t do it on their own. ‘Gamblers Choice’ followed in 1980 and introduced the Taxi label,

Sly & Robbie’s own label. Black Uhuru’s album ‘(Stalk Of) Sensimilla’ was also issued at the same time on the label. Island issued the album in the UK, which meant of course that Sly & Robbie were now subject to Island Records machinations.

Typically Island got off to a good start. ‘Presenting Taxi’, released in 1981, is an excellent various artists album, including great works from Dennis Brown, Junior Delgado, Wailing Souls, and The Viceroys. ‘Raiders Of The Lost Dub’ from Island was also well received. Following it was a tedious dub of Black Uhuru music called ‘Dub Factor’ which was released in the US on Island in 1983. ‘Rebel Soldier’ featuring the mixing skills of Anthony ‘Soljie’ Hamilton, the current engineer at Channel One, came next in 1983. It was much better. As the sleeve states – “This album gets down to the roots of the music.”

‘Crucial Reggae’, another various artist set with music from Carlton Livingstone, Dennis Brown and Yellowman, ‘Taxi Wax’ issued on Taxi in Jamaica in 1984 with music from Sugar Minott and Dennis Brown, and the ‘Unmetered Taxi’ LP which featured ten cuts of the ‘Peanut Vendor’ rhythm with fresh and young talented artists like Frankie Jones, Anthony Johnson, Patrick Andy, Hugh Griffiths, Earl Sixteen and Jackie Statement, all show and prove that the roots of the music is where Sly & Robbie are always at their best.

It’s time for a major record company to recognise that fact, and release and promote albums like those mentioned above with the same vigour with which Island promoted ‘Language Barrier’, a funk album from Sly & Robbie which came out in 1985. Until a company is prepared to make

such a commitment talented musicians and producers like Sly & Robbie will never get the full recognition they deserve, and will be forever at the beck and call of the rock music business, whose attitudes and interests change as easily as the wind.

The biggest thing you’ve been responsible for this year (1978), has been to change the beat. What do you call it?

You get a certain rhythm, some they call it ‘Sly Tackle’, some they call ‘Jumpers’, and some Bouncers’. And the type of drum I play on ‘Don’t Look Back’ by Peter Tosh, I call a basketball thing.”

Sly then goes into amazing vocal impressions of different rhythms.

‘Sly Tackle’ is like the beginning of ‘Bredda Gravalicious’ by the Wailing Souls. Jumpers’ is like ‘On The Beach’ by Johnny Clarke. An album which features some of his best work is ‘Cool Ruler’, Gregory lsaacs’ album.

I asked him what he would call say ‘Party In The Slum’ on the ‘Cool Ruler’ album?

I can’t recall certain tracks, but there are a lot of conga drums playing – yeah, instead of using the snare, right, I was playing congas. I just place the conga, in place of the snare, ’cause right now were going into the conga sound in reggae.”

Someone said it was tom toms?

No.

It’s also been said that the board is responsible for most of the drum sounds?

No, it wasn’t the board really. It was me – then the board it’s when they’re mixing the dub, you put the reverb on, like echo, you know, on the drum. Turn down the vocal, and turn it up for the drum.”

There seem like two different types of bouncers. On ‘Money In My Pocket’ there seems to be a booming sound. How did you get that?

Well ah, we was recording this tune, John Holt’s ‘Have You Ever Been In Love’, that’s at Channel One, right. We working on the chords, and…, do you remember the original version of ‘Sun Is Shining’ that the Wailers did? They had this rhythm guitar going (vocal impression of rhythm guitar). So I tune my side drum almost to the pitch of the rhythm guitar. So they said, “lt sounds great, we’ll try it.”

Are the drummers in JA trying to copy your sound or trying to adapt it?

Some of them copy, some have their own style. Everyone of them alright.

When you record for Channel One, you’re with the Revolutionaries, then with Joe Gibbs, the Professionals. Is there a difference?

The Revolutionaries are myself, Robbie, Ranchie, Dougie, Ansell Collins and Sticky. The Professionals are myself Lloyd Parks, Bo Pee, Frankie & Robbie.

The new drumming – is it easier for a bass player to find a bass pattern?

When a singer comes into the studio, we listen to the song. And the bass player may start a line. And I’ll try to find a drum pattern to fit it. That means if the drum pattern fits the whole melody of the sound, any bass that is playing is supposed to work right, ’cause if you try to find a rhythm to match a song from the drums, you find the bass fit right. Sometimes again you can play to the bass line, instead of playing to the song. But you have to listen to the two of them very close.

The album that Front Line released, it didn’t really show you in a good light.

That wasn’t really like an album. It was some rhythm tracks they said they liked, and released them. Like now, I’m a musician, you can’t really make an album that just features the drum. Like, I play on so many records in Jamaica any producer could put out a dub album with me playing on it. I’m doing one now from the musician’s point of view, not just the drummer’s.

How about the album with Derrick Harriott?

Just some rhythm tracks. He put it out with my name and the Revolutionaries, to get it to sell. If he put out a Derrick Harriott dub album, it wouldn’t sell as much.”

What drummers did you listen to when you first started to play the drums?

A drummer that used to play with the Skatalites, Lloyd Knibbs. Al Jackson, Harvey Mason, Steve Gadd, and Billy Cobham, all drummers Jack DeJohnette, every drummer that used to come by, ’cause you’ve always got something to learn.

Is it hard to get into the drumming session scene in Jamaica?

Well, it’s like I play 90% of the tunes that come out of Jamaica. Sometimes I even go and overdub some drums that other drummers have played on. So I would say it’s hard. Me and the producers move good. I give them some good ideas, and they suggest certain things to me, they say “Try it”. It’s just understanding each other. So, I move good with everyone and they give me sessions.

It seems like every era the music changes, the drummers have changed. You mentioned Lloyd Knibbs – that was ska. Did he go into rock steady?

Rock steady, first tune came from Coxsone, that was Bunny Williams and Fil Callender.

Of In Crowd fame?

Yeah, then it went into reggae, when you had Hugh Malcolm, Winston Grennan, Tinleg, and Santa. I was playing for them times, too, but I was feeling new. The first song I played on was ‘Night Doctor’ Upsetters, Ansell Collins production. The second was ‘Double Barrel’. That was when I was fifteen.”

What age did you start at?

Professionally, fifteen.

Why do you think that you exploded on the scene in 1974/75?

I listen to music 24 hours a day, all form of music. I went to see a movie called ‘Soul To Soul’. After I see it, I felt reggae need something, after the part with the drums and they was all dancing. If we play regular pattern on the drums, a sort of African pattern, anything you do on drums is going to be African – something you can dance to. I get some time from JoJo. Me and Jo Jo are good friends. And I said I ‘ve got this rhythm I want to do. Anything you want to do with it, you can do it. So, Ranchie came up with the bass line, and that was right. I was playing fours, but I didn’t like it. Sol change it about (vocal impression of the intro to ‘Right Time’). And so it was recorded. And when it was released everybody say it was effects from the board. But I told them no. Jo Jo started to record a lot of sound that way. And that’s how the big change came about. The whole idea was musicians feel, but nobody wanted to take a chance. The only way to prove it to them, was to take some time and do it.”

Up until then, it seemed like it was mainly the producer who dictated what the sound was going to be. Now, with yourself, a drummer coming in and saying, I’m going to do this sound, have you changed it?

Well, sometimes you have to do what the producers say. But now he listens more to the musicians’ suggestions.

You’ve got this new sound ‘Bouncers’; can you see any other sounds coming?

Some of the tunes that I played on a long time ago. Some of them have just been released. Some of them haven’t. The Wailing Souls ‘War In The East, War In The East’ (‘War’), that’s in a different style. And that was the only song I did till now in that style.

‘Bredda Gravalicious’ from the Wailing Souls has an unusual drum sound, how did you get that?

“What I did was to work two drum in. I use two snare all the time I’m recording.

lt’s very similar to the drum on metal sound that Lee Perry has used. Mention of Scratch brings another tune to mind.

You remember ‘Police And Thieves’, I played on that. With that I had to rough it up to get the feel.

Lee Perry uses Michael Richards a lot, doesn’t he?

Well, sometimes when Mike is off, I play for him. But if I were in Jamaica now, I would be booked for a full week. So if he wanted me now, he would have to book me last week, for maybe next week.

•

10 MINUTES WITH SUPERSTAR DRUMMER SLY DUNBAR (THE INTERVIEW)

By Stephen Cooper – February 19, 2019 – Studio City Sound, Studio City, California

On February 19, thanks to legendary sound engineer Scientist (also known as Hopeton Brown), I was introduced to Mr. Dunbar at Studio City Sound (in Studio City, California). Dunbar and Shakespeare were working on a project with Scientist, Odel Johnson (a versatile Jamaican-born, Canadian-based artist), guitarist Tony Chin, and keyboardists Franklyn “Bubbler” Waul and Michael Hyde.

Although Mr. Dunbar was extremely busy and under considerable time pressure, he graciously agreed to speak with me for a few minutes as the musicians finished their preparations for recording. We spoke about his memories of Bob Marley and Dennis Brown, how Bob Marley would feel about the “state of reggae music,” why Dunbar and Shakespeare left Peter Tosh to play for Black Uhuru, the Grammy Awards, the best recording studios, and finally, the Jamaican government’s failure to properly honor some of the country’s most talented and accomplished reggae musicians. What follows is a transcript of the interview, modified only slightly for clarity and space considerations.

Recently we celebrated the 74th earthstrong celebration for Bob Marley. Are there any memories you immediately think of when you think of Bob Marley?

I think of Bob Marley as a great icon who was part of the movement of [making] reggae what it is today. And I remember Robbie and myself used to go and check him when he used to come out to New York. And we’d talk, and sometimes we’d buck up in the music store and he’d always say to me, “Sly, you should open up a music school in Jamaica. A music store.” And I’d laugh. And he’d always say to me he wanted me to come play a whole album for him. And because I used to play with Peter Tosh, he’d always run a joke and say, “you don’t want to come play with us?” And I’d say, “No, man.” And then one night when he come back out of exile – he’d been away from Jamaica for a while, when he got shot – and Lee Perry kept [a] session, [and I] went over to Lee Perry’s studio, and we did like three tracks with him and I did –

Punky Reggae Party [was one]?

Yeah, the recording of Punky Reggae Party. Yeah.

Do you think if Bob were alive today he’d be happy with the “state of reggae music” in the world?

He would change it. He would go and write some wicked songs. Because he was a part of the movement. He never really shun it, you know? And when he hear a movement’s coming, he always join it. Because he’d know it was an evolution, and you can’t hide [from] it. So he would be a part of it, yeah man.

Would [Bob Marley] be happy with the direction the music has moved in?

Yeah he would be happy because he would set the trend, and everyone would follow.

You also worked closely with Dennis Brown. I know you [played] on [his] original “Money In My Pocket.”

Yeah. And the re-cut.

When you think of Dennis Brown, what are one or two of your memories [of him] that come to mind?

He [was] a great performer. Been playing with him [since] we were very young, [back when he was in] a band called the Falcons. And I did a tour with him. And I did a lot of recordings with him. He [was] a true artist. A great person. And a very loving person. A very kind person. A great icon.

So much is written about Bob Marley. Is there anything about Bob Marley that you think is not emphasized as much as it should be?

He was a great person. He was a nice person. I [was] around him quite a bit. The times I [was] around him [he was] a very cool person. He [was] into his music, you know? His music [came] first.

You have said before that when you [played] with Peter Tosh, that [that] was one of the most experimental times in reggae [history], and that you guys were really experimenting with the music

Yeah, yeah. In that time, in the 70s there was a time when we started to experiment [with] reggae. Reggae started to open up into different areas, you know? And Bob seen it. He wanted to be a part of it, too. Which he did. He was a part of it. He came and he made a song called “Exodus.” In the kind of rhythm we were making at Channel One [recording studio]. So Bob is like a groove master. He would listen to what is happening. And if he was here today, he would make some wicked [music], because he was always [attune to] the next movements for reggae.

Why did you decide to move from playing with Peter Tosh to working with Black Uhuru?

Because we [(Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare)] were producing all these artists while we were playing with Peter. [And] Black Uhuru music is like a different kind of groove from what we played for Peter. It was a hardcore cutting-edge thing [and] we felt we couldn’t play that style for Peter, because he wasn’t singing that kind of music. So we played Peter’s music just the way he sees it. And we play[ed] Black Uhuru music the way we [felt] it, and thought it [should be].

What are your thoughts about Sting and Shaggy winning the Grammy this year for Best Reggae Album?

It’s great. ‘Nuff respect and congratulations to them both, you know?

The Grammys are often criticized for being biased against female reggae artists. Also they’re criticized for being biased in favor of the Marley family –

TI don’t know. I don’t know.

Are the Grammy [awards] still meaningful for reggae fans to pay attention to?

Well, it’s meaningful for reggae artists. Because you get that [award] in your hand [and] you always cherish it. Because you look at it and say this is the work I’ve done over the years.

And it opens doors that might not otherwise be open?

Yeah.

Selecta Jerry, a DJ in New Jersey whose show I listen to called “Sounds of the Caribbean,” a show he inherited from [rocksteady icon] Keith Rowe, he played a song last week called “Jah Children Dub.” It’s a wicked song [and] it says on the 45 that you’re featured on it. And Selecta Jerry wanted to know if you were just featured in the dub on that? It’s a tune [produced] by Roberto Sanchez, and it says [on the label] that it features you.

Well there are so many records I play on, sometimes I don’t remember [them]. (Laughing) But if it says that on the record, that’s it.

(Laughing) It’s a great tune. A lot of [really] good [roots reggae, rocksteady, and dub] music is coming out of [producer] Roberto Sanchez’s studio in Spain.

Yeah.

He’s been working with Keith and Tex releasing new music, and he’s been working with you as well. Why is his [studio] able to produce such good, old school-vibes over there?

Well this is what he’s focused on. And he probably [went] and researched the music [because] this is what he wants to do. And [he] realized how to put the music together. So he probably did it in that manner. And you stick with it. And perfect the thing.

You’ve played in so many studios, Mr. Dunbar. What are the best recording studios in the world today?

A: Today? (Laughing)

Yeah, [or ever]. When you think of [studios] where you would most like to play, [which] are some of the best ones?

Alright. Alright. Let me tell you some of the best recording studios. There are a couple of studios where I think my recordings came out very great: (Nassau) Compass Point [studio] with Grace Jones, Channel One studio, and Dynamic Sounds studio. We did Serge Gainsborough’s album at Dynamic Sound. We did all the Black Uhuru stuff and heavy stuff at Channel One. And some of the Taxi [Cab label] stuff. And the Grace Jones project at Nassau. Those three studios I think the recording was very great for me. They made the drum sound good.

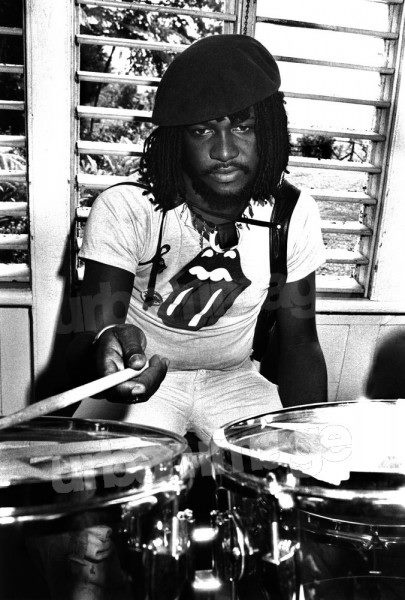

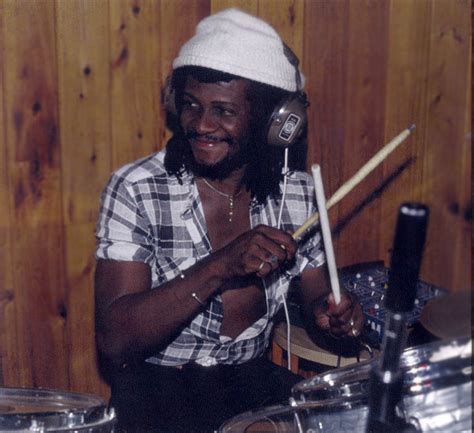

Sly & Robbie Channel One 1984 (Photo: Beth Lesser)

Do you have drum kits on all continents of the world?

(Laughing) No, no, no. I live in Jamaica.

One [last] question that I always ask reggae artists. Why is it that there seems to be such a lack of support even now with the Jamaican government in terms of both honoring the veterans ?

I don’t know, you know? ‘Cause I don’t care if they honor me or anything like that. I don’t know. But I think they should. Because there are a couple of people that have done some great work. Even this drummer by the name of Joe Isaacs. He did a lot of stuff. He played on Johnny Nash, not “I Can See Clearly,” [but] the first Johnny Nash song “Hold Me Tight.” And he played on a lot of Studio One [records]. He was the one who started playing rocksteady.

And he hasn’t received any recognition [from the Jamaican government] for that?

No, no. He hasn’t received anything. A lot of people don’t know the history of the work musicians have done in Jamaica. So we’re trying to organize to see if he could get an O.D. [(Order of Distinction)] or something for the work he has done. He put in a lot of work.

It seems there are a lot of [very accomplished Jamaican] artists I’ve come across like Keith and Tex, Scientist, [many] who’ve never been [properly] recognized by the Jamaican government [for their tremendous musical achievements].

Well like for Joe Isaacs, he has [played on] so many songs. The Jamaican government doesn’t keep track of what recording artists do. Somebody has to be assigned in the culture [ministry]. Somebody has to go and tell them because they don’t know. Because there’s no [serious] collection of anything [concerning reggae music history and artifacts] there. Remember [back] in those days, musicians’s names weren’t recorded. Nobody knew who played [on recordings when they were released]. It just kinda changed when [Robbie and I] started doing recording in the 70s. [Musicians’s] names started appearing on record jackets. People would see the musicians who were playing. But Joe Isaacs has played on all these songs, and nobody knows his name because he was never mentioned. Me, as a drummer, I could hear the sound and tell his style of playing.