December 1, 2019

Reporter: Stephen Cooper

Part 1

When it comes to reggae music, and similar to when I interviewed your brethren [legendary guitarist] Tony Chin, I basically had to give up trying to create a [comprehensive] list of all the famous reggae stars you’ve played with over the more than four decades you’ve been a professional drummer – the list is just way too long to complete.

(Laughing) Yeah.

However, correct me if I’m wrong, but my research shows that, in addition to being Ziggy Marley’s drummer for about twenty years, just a partial listing of people you’ve recorded with as part of legendary studio bands like the Aggrovators, the Observers, Roots Radics, Soul Syndicate, and more –

Like the “Impact All-Stars” which was Randy’s.

Randy’s All-Stars?

Impact! (Laughing)

Randy’s Impact All-Stars! And [you did this] for producers that included Bunny Lee, Lee Scratch Perry, Duke Reid, Niney the Observer, more?

Yes.

And these are [just] some of the [reggae stars] you’ve [recorded] with: Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, both separately and when they were together as part of the Wailers –

And Bunny Wailer.

And Bunny Wailer. [Also,] Burning Spear, Dennis Brown, Big Youth, Jimmy Cliff, Johnny Clarke, Ken Boothe –

Um, I performed with him, but I swear (laughing), all the years I’ve known Ken, I’ve never actually recorded with him. But I did a couple of shows with him back in the [day].

Gregory Isaacs?

Oh yeah.

Then, the Mighty Diamonds, U-Roy, also I-Roy, John Holt, Horace Andy, Max Romeo, the Abyssinians –

Yes.

Now I was surprised by this, but King Yellowman?

Oh yeah. I did early stuff with him when he was recording for [producer Henry] “Junjo” Lawes.

“Them A Mad Over Me?” That’s one of my favorite –

(Laughing) Yeah.

Oh man, that is amazing. And then [there’s] Yabby You?

Oh yeah.

Augustus Pablo?

Yes.

And then I know this because I asked him, [but] as part of the Roots Radics, Scientist?

Yeah! I first met Scientist up at King Tubby’s studio. He did a lot of work with King Tubby. I think that’s actually where he started.

And then [also], as you [just] said, there’s King Tubby, Pat Kelly, who (unfortunately) recently passed away.

Yes – yes.

Wailing Souls?

Yes.

n fact, I have to say, I saw an article when I was doing research [and] I couldn’t figure out a way to ask you a question about it; I dug up a Los Angeles Times article on google from 1993 that talked about you and your impressive drumming style [while performing] with the Wailing Souls. [It noted] you had a “muscular style,” and that you ended one of your rolls with your elbow!

(Laughing) Okay!

So I was like “wow” when I read that.

(Laughing) You know what, man, sometimes crazy things happen. Like I tell people all the time, people say, “Oh, you do this, you do that,” but a lot of times these things that I do – it’s unplanned. It just, it just, at the moment it just happened. Even sometimes I’m like wow, where did that come from? (Laughing)

And then, just to finish my partial list [of reggae stars you’ve recorded with]: Delroy Wilson, Cornell Campbell, Tappa Zukie, and like I said, way too many more to name –

Yes, all the roots people you can think about. Except a few. But all the roots people[, really]. Except my only regret is not working with Ken Boothe, you know? Well it’s not a regret because that’s part of the business; you can’t work with everybody. I [also] did stuff with Alton Ellis –

Yeah, I know, even people I didn’t mention, big names –

Joe Higgs.

Wow, Joe Higgs. Now if it’s okay with you, I want to ask a few biographical questions about your youth and upbringing? You grew up in Greenwich Farm, in Kingston, Jamaica. True?

Yes.

Is that also where you were born?

No. Actually I was born in Kingston, Victoria Jubilee [Hospital]. Which is downtown [on] North Street. You have the Kingston public hospital, and then across from that you have the Victoria Jubilee; they both faced one another.

Would you also agree, despite the beauty of Jamaica, Greenwich Farm, at least when you were growing up, that was rather a tough neighborhood, a ghetto, a garrison?

Well, Greenwich Farm wasn’t really a ghetto as such. Greenwich Farm was a multi-functional place. It was a beautiful little city. And that’s where the beach was. Where you go buy fish.

Tony [Chin] said his dad was a fisherman.

Yeah! Yeah. That was the place, when you need some fresh fish, you have to come to Greenwich Farm. And then you had the oil refinery down there, it was, it was –

A vibrant place?

Yes, yes. It wasn’t a place where a lot of violence was happening. There was more happening in Trenchtown than Greenwich Town. And then you have these transplants start happening. And all of a sudden this guy from here and that guy [from there] start having beef. It gradually became, you know –

But when you were growing up [there], did you feel comfortable and safe?

Yes, yes.

You didn’t feel threatened walking the streets or anything like that?

No, no, it was a community. Everybody knew everybody. That was the beauty of Greenwich Farm.

Were you raised by both of your parents growing up?

Unfortunately, no, just by my mom. Great mom, too! (Laughing)

What did your mom do for a living when you were growing up?

Well, um, she just used to do domestic stuff. She used to work at the drycleaners, and then she was a stay-at-home mom; when I had a stepdad, she was home taking care of me.

Do you have brothers and sisters?

No, [I’m an] only child.

Is there anyone in your extended family who is musically talented and/or into music like you?

Not that I know of. [But] the unfortunate thing is I never knew any of my mom’s family. Except for maybe one time I ran into a niece of hers; and that never worked out so well; there was kind of a vibe and that was it. But I don’t know if there was anyone in the family that was musically inclined, or musically talented. My mom, she was a church lady. So she used to do a lot of singing, and going to church and singing, but she wasn’t into musical instruments or whatever.

In a March interview you did this year with Techra Drumsticks –

Yeah, that’s who I’m endorsed with.

Oh, I didn’t know that.

Yeah, yeah, see I got their sticks.

Oh cool. These are the ones made out of carbon fiber?

Yeah, these are carbon fiber. I even have my name on them.

Oh man, that’s awesome.

You can have this. This is yours.

Oh no, really? Oh man, that is so nice of you. You sure?

This is yours, brother. I got a bunch. Come on, man. (Laughing)

(Laughing) This is awesome. Oh man. What a souvenir. You got me [having] goosebumps. Now, in this interview that you did with [Techra Drumsticks], you said one of the challenges you had growing up while trying to play the drums in Jamaica was not having a proper [drum] kit to play on really until the age of maybe 16-17, when you began playing with the Soul Syndicate –

Yeah I had more access to a drum kit [then].

And [my understanding is that] all the other drum kits you played on from when you began playing at the age of 11 with the St. Peter Claver drum corps, to the age of 14, when you joined your first band, “Kofi Kali and the Graduates,” were these kits you kind of jiggered and put together yourself using various drum components that you had – even metal that you got from [legendary Soul Syndicate bassist] Fully Fullwood’s father, and your stepfather, too, who were working together. I think they were welders. And you mentioned you were able to make some stands and things out of metal; I was so impressed by this.

Well, I think what happened, it’s kind of like two separate things. Because sometimes when you’re talking to a lot of these foreigners, they kind of get things a little bit twisted. The information is right, but it’s not connected

And I may have it wrong –

No, no, no. In drum corps, I was what they call a “quartermaster.” I took care of all the equipment. I made sure what goes out comes back in. That everything is stacked nicely. The room was a little bit bigger than this room [that we’re sitting in now], with high ceilings, so all the drums and the bugles –

This was part of a church?

Right, right. So what happened, in that room, is where I actually tried to put a drum kit together. You had that big marching drum, that one you put on your chest, it was maybe a ’26 or something. Then they had a little rinky-dink pedal. I put the pedal on. I didn’t know what I was doing –

[You were just doing] what you’d seen in pictures?

Right, right. I said, “Okay, I’m gonna put a drum kit together”. Then they had a little snare – I think it might have been a little piccolo snare or whatever, I didn’t know what a piccolo was. I didn’t know it was a piccolo. But it was a small snare. And there was a small stand, so I put it on the stand. And then on the bass drum, I didn’t have a high-hat; there was like a little cymbal stand that you could clamp onto the bass drum. So that was all I had: I had this big bass drum, the snare drum, and that little [cymbal] stand.

But you could practice with it?

Yeah so, I was trying to mimic what I heard on the street. Remember now, I was in the drum corps. I was doing military-style things. I was an “all-around” as they call it. Because I used to play snare [drums], tenor drums, cymbals, bass –

All as part of the drum corps?

Yeah. I was flag-bearer, I was a rifle-bearer, and then I was a drill instructor at one point. There was a junior band. So I was helping them. And there was this great guitar player. I think he’s still alive. Bobby Aitken. You’ve heard of Bobby Aitken?

Yeah, and I think I’ve heard you [tell] this story before. [Bobby Aitken] heard you playing and he came and helped you?

Yes! Yes!

Even though he was a guitar player, he wanted to show you some of the reggae drums and riddims?

Yes! He’s the first, I can say –

He had a band called the “Carib Beats?”

Yes, the Carib Beats. What happened [was] he used to give guitar lessons at the church. He was one of the premier musicians in Jamaica at the time. There was a bunch of musicians and he was part of [them]. He had a band called the Carib Beats and they played a lot of songs.

So he was a pretty known guy?

Of course.

So when he saw you playing on the drums, and came over from that part of the church where he was, did you know from seeing him [before], who he was?

Yeah, I knew who he was. But I didn’t know much about him. But see what happened is there were two churches. The building I was in was the old church. And the room that I was in they would call, in Catholic terms, it’s a “sacristy.” Where the priest would go and prepare his little wafers. So they built a new church over on the other side; so they used the old church as a recreation center. And they do everything there. Because it was a school also. So the room which was the old sacristy was where all the [music] equipment was. So [Bobby Aitken] was in the other side of the church giving guitar lessons. So I’m in there going “Boom—Ching—Boom—Ching—Boom,” right? So, he heard it because I had the door open, and so he came from the church side. Like from the altar area. And he came in, and he said, “Ok, listen, I hear what you’re trying to do, but you want to have the snare drum and the kick drum fall at the same time. And then you play like an eight-note over it, ‘Tap-Tap-Tap-Tap–’”; I said, “Okay, cool.” Because he was one of the rocksteady cats, one of the real deals. Bobby Aitken – I’ll never forget that. He was the first man who point me in the direction and say, “This is the way you have to go.” That’s how it all started.

Also in that March interview that you did, you said your mom couldn’t afford to buy you a full drum kit. And they are expensive pieces of equipment. But you also said that, “at that time in Jamaica, music wasn’t really looked upon as a real profession. So if you talked about being a musician, my mom would say you better go find a real job.”

Exactly! (Laughing)

So what did your mom and other family think when, at age 14, you’re already playing in a band with Kofi Kali and “the Graduates,” which I understand was a nightclub band?

Well at 14 years old, I was still in [the] drum corps. So it’s actually 16. I left drum corps at 16 years old.

Even 16 is young, but I was like, 14, how was he even getting into the club?

(Laughing) No, no, no. I left drum corps at 16 and transitioned right into playing with Kofi Kali [and the Graduates]. But the thing is this: I never just started playing with them right away. Because this drummer, Leroy “Horsemouth” Wallace –

Yeah.

He was the drummer playing, because you know, he was around, he was [drumming] before me.

Is he older than you?

I guess. But he has to be because he was one of “the guys.” He was playing for Studio One. So Leroy, I have to give that respect to him. He was before me. So he would play with a lot of people. He was the drummer playing there [with Kofi Kali and the Graduates]. But he wasn’t permanent. So I don’t know, it’s kinda weird how I got there, but I heard the music actually, it was in my area. I lived in Greenwich Farm on East Avenue. And if you come all the way up East Avenue; you have East Avenue and Spanish Town Road. And on the other side of Spanish Town Road, there was a big electronics shop. And they used to sell records. And they used to fix electronic stuff like radios and record players –

Are you talking about the Hoo Kims’ shop?

No. Their shop, their business place was beside this guy’s. (Laughing)

I’ve heard you describe this area in other interviews and [it sounds] like a music center. Everyone [there was] involved in music. Such a creative spot!

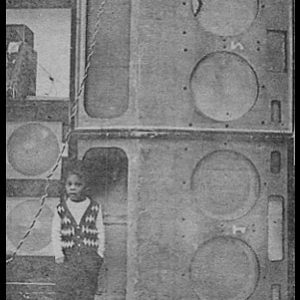

Listen, man. This is why I have to tell you something. You see, in Jamaica, Jamaica was always this vibrant [place]. I can remember my childhood. It was excitement. Because there was so much music. Everywhere there was music! Because you had the bars, and every bar had a jukebox. Every bar had a jukebox, and there was music playing. And, you know, some guy might have a little stereo system in his yard. People used to make their own speaker boxes. And they would buy a turntable. Get a little amplifier –

The sound system culture is just amazing.

That was a big part of Jamaica. And there was a balance where you had, the sound system was like every weekend; the sound system in my area. I was surrounded by three dancehalls. You want to talk about dancehall music? Okay, dancehall was a place, as we all know. From Friday to Sunday, you’d have Sir Coxsone Downbeat, you’d have Duke Reid, or Jack Ruby (laughing) – it was excitement, you know? So what I’m saying now is, because I was in the area, I would pass by there, and I think I went over there to where Kofi Kali and the Graduates were playing. And I think the drum kit was there. And the guy Kofi was like, “Can you play drums?” And I said, “I can try.” And for some weird reason he allowed me to practice [with them]. It’s kinda weird how that happened; I don’t remember the exact details. And then, when I started actually playing with the group – you know Richard Daley from Third World?

Was he part of Kofi Kali and the Graduates?

He was the guitar player. He and I started there at the same time.

I had never heard of this group Kofi Kali and the Graduates, but I understand that it also included Earl “Bagga” Walker –

Earl “Bagga” Walker was the bass player. Glen DaCosta [was] on saxophone; he was still with the military but he would do that on weekends and stuff. [The band] never stayed around for a long time, because we just used to do like little club stuff here and there, you know what I mean? And Kofi Kali? He used to live in America. And he played the alto sax. He would remind you of people like a Coltrane kinda vibe. Or a Charlie Parker.

Jazzy?

Yeah, he used to play a lot of jazz. But we never really played “jazz” [as a band]. It was a mixture. Like I wasn’t a jazz drummer. I didn’t have a clue.

Your most recent [solo] album “Watch You Livity” is very jazzy in a way.

Yeah, yeah. Because I was influenced by so many great musicians both in Jamaica and the [rest of the] world. So that’s where the whole thing all started.

But to go back to your family for a moment, when you started to do this thing, where you started going to these [gigs], whether they were small or big, or whatever, with Kofi Kali and the Graduates, and you’re playing with them and doing this band thing, what was your mom saying to you? Was there conflict? And was there some point where your mom [and] other family that you have –

Just my mom. Just my mom. It was just me and my mom.

What was her first name?

Monica. She passed away a few years ago.

I’m sorry to hear that.

But she was 92 though, she lived a long time. Like most parents, she always wanted good for her kid. Her whole thing from her time growing up was, music wasn’t looked upon as a profession. It was more of a hobby thing, a weekend thing, it wasn’t looked upon as a business. So, most good parents would advise you to get a job. And a job means going out and working out in the field. Going out and working in a factory, or wherever.

Wherever there’s steady pay?

Right. That was her thing. Like every good parent. But the thing is this: she never hindered me. [She never said,] “Well, this way or the highway.” She was giving me good advice, then she allowed me to do what I was doing. And what happened was, at first, my ambition was, I was going to join the military or the police force. I was on my way. I was getting ready to go to police training school! I was getting ready to do that. And I don’t know if this stopped me, but one night, I was at Kofi Kali’s place, right? And there were two cops who used to do “beat” duty in that area; they would walk back and forth. And we were in there, and all of a sudden, we heard shots. And we came out and I saw these two cops – one was lying on his back. Because they would pass by every day, and say “Hey, how you doing?” I knew them. Not as “friends,” but we knew them by just seeing them pass all the time. And that was the first time [I saw someone shot]. Ok, you watch the movies, and you see [someone get shot] right between the eyes and stuff? And that was in the movies. This was the first time I actually saw a real human being with a bullet in the middle of his forehead. Right between the eyes. And the guy who died like that, it’s weird, because he usually walked with his hands in his shirt; like a comfort thing. And he fell back just like that, with a bullet in his head. And I saw that, and the [other] cop, he was shot in the head, and blood was coming out of his head like a pipe. And then I helped, you know, we all helped to put him in a taxi for him to go to the hospital.

Santa, man, you’ve been through some [heavy] stuff.

And when I saw that I was like – that kinda turned me off right there [from being a policeman]. To be honest, that turned me off when I saw that. Because I was still playing drums at the time. And from then on I realized, you know what, this is gonna be my life. So, with that said, I started doing gigs, and then I would get a little money. It wasn’t a lot of money. But even back then the economy was different. If you had like twenty dollars, back then that was like a lot of money; you could do a lot with twenty dollars. And I was a kid. I didn’t have any responsibilities. So the first time I went out and did a gig or a recording session, and I came home, she was like, “Where did you get all of that money!?” I said, mom, calm down, I worked, I went to the studios and they paid me. I was like 16-17. And she was like, “Well you know, if you want to [play music,] do it.” Because she wasn’t trying to hinder me, but when she saw that I brought home money, and I gave her money, she was like, “Do what you have to do if that’s what you want to do; go ahead.” And that was it.

You said your mom passed three years ago; so she saw towards the end of her life all the success you’ve had touring all over the world –

But she never saw me play.

Wow. Why not?

Because she was a Christian lady. She was into the Bible and the church. And it’s not that she didn’t like secular music, but that wasn’t her thing. She knew I was in the drum corps, but she never saw me march or do nothing. She allowed me – and the thing is this, she was happy, even though she never saw me play, she was happy that I was doing something meaningful to keep me out of trouble.

I’ve heard you tell the story several times [in other interviews] how you ended up at St. Peter Claver’s [drum corps] because you walked to and fro from school –

Yes.

And you heard the [church band] playing, you heard the horns, you heard the drums, and one day it just so happened that the gate is open and you walked in, and it happened to be the same day they were auditioning for people to join –

Yeah.

And you said, “sign me up.” And I was curious because I think you also said, this was a Catholic Youth Organization, a C.Y.O. –

Yes.

– because you were raised by your mom exclusively, what did she think about [that]? Was this fine?

She was just happy – okay, because, there was a church in my neighborhood –

Because her denomination wasn’t Catholic, was it?

No, not really, but she didn’t have a preference for me, she just wanted me to go to church. And there was a church in my neighborhood, a Catholic church also, it was called “Holy Name.” So I was already going to church. I used to go to church in the morning and then I would go to Sunday school. So she had me in a routine. But the school I used to go to – I used to go to Maxfield Park primary school, right – and I had to pass by [St. Peter Claver], that was on my route. So coming from there, from school, I would hear the band and the music playing. But the gate was always closed. So I would hear it and be like “Oh man,” but then I would just go home. To go do chores and stuff like that. But this one day, I don’t know what drove me to do that, but I heard the music and I said, “You know what, let me go over there and see what’s happening.” And just like you said, the gate was open. I said, “Okay, this is like a sign.” And I went in. Normally, I [would be] just outside looking in. But the gate was open, so I walked in and I saw this little group – this little commotion going on. And I realized they were recruiting new people. So I joined.

There must have been a time when you started to get into Rastafari, when Rastafari came into your life; when did that happen, and when did this become part of your music and your spirituality – and was this an issue between you and your mom?

Well, you see, by me starting in the church, I was already on a spiritual journey. Because I grew up like that. I grew up in the church, and I grew up seeing my mom going to church [and] reading her bible. So when I [was] [growing] up, I started hearing of the Rasta culture, [but] I didn’t understand it; you know, people think you grow up in Jamaica, you should. [But] as a kid growing up, [we] were told that Rastas just smoke weed and –

[That they are] “Blackheart men?” Steal your kids –

– blackheart man and all that kinda stuff, right. But the thing is this: as a little kid, I used to be around this blackheart man, and he never did anything to me.

So you had some Rasta elders in your neighborhood?

Okay, so I was living in area called “Constant Spring.” It was a neighborhood; I was living up in that area off of Constant Spring Road. Like you’re going toward Stony Hill.

This is still in Greenwich Town?

No, no, no. This was before that; because I moved from there down to Greenwich Town. Because I was living like the middle class life, the good life. I had this stepfather who was everything, whatever. He and my mom fell out and she had to just –

Times got tougher?

Yeah, times got tougher. So we moved downtown. Which was still cool, you know? But when I was a kid, I used to live in this nice house [in a] nice neighborhood. But then, over across the way, there was a little area where it was like a ghetto; [now] I didn’t know what a ghetto was then because I was like a baby, you know, I was small. And over on that side there was like a ghetto. And you’d hear drumming and you’d hear all these things. And you’d hear a lot of loud noise. It seemed like they were always having a commotion over there all the time. And there were some bushes over there, like a little gully. And as a kid I used to go play, I used to go over there. [And] there was this Rastaman; because back in them days, Rasta had to hide. They had to live off of the grid because they were hunted by the cops. Nobody would want to rent – they couldn’t rent a house; they couldn’t rent nowhere; [they] had to live in the bushes.

Scorned?

Exactly. So this Rastaman, he was living in the bushes. So, I went over there. And I saw this man cooking his little food. I didn’t eat anything but I can remember that as a kid. I don’t know if he was smoking, because I didn’t know what weed was. But I used to go over there. And he used to talk to me. His locks [were] like real thick, and [were] like one, like a big mat or something. They used to call [Rastas] “mop heads” at that time.

Did his locks and what you had heard about [so called] “blackheart men” and all that, you weren’t at all intimidated or scared by him?

I didn’t know, I didn’t know – the most I can remember [about him is], he was kind. He wasn’t this scary person that I would later learn about; people talking about “blackheart man.” And then when I grew up and realized who they were calling a blackheart man, I said, wait a minute, but I used to go there. And then, when my mom found out that I was there, she got scared, and said “Don’t ever go back over there again.” But the blackheart man they were talking about was a humble Rastaman. And he was very, very kind. So I don’t know if that changed my perspective, but it had an impact.

And so how did you then, when you started getting older, and learning more about [Rasta culture], was it through playing drums and playing reggae music that you started to get more into the Rasta culture and belief; were there people along the way who were [teaching or telling] you stuff about Haile Selassie, and Marcus Garvey – teaching you, or sharing books with you, anything like that – as you were [growing] up?

Well, it was during [my] drum corps time. And, of course, if you grow up in Jamaica, and you’ve never heard anything about Marcus Garvey, then you’re in a hole somewhere; you’re under a rock. So we knew about Marcus Garvey; I used to be around people who maybe knew [Garvey], or [who] grew up when he was doing his thing back then. And I used to hear a lot of stories about Marcus Garvey, and his quest, and his journey. And then I started to learn about that; we used to learn about Marcus Garvey. But it was then that I started to hear the Rasta drumming, and then little by little, Rasta was getting more liberated. More out-front. But it was still like a battle between them and the police. They were really discriminated against. Rastaman going down the street with his locks, they used to hold him and trim his hair and do all kinds of dirty things. But then I started learning about what Rasta really was. I used to hear Rastaman talk about the Bible. So once I started hearing about Rastaman reading the Bible and talking about the Bible and God, I said why are people fighting against these people –

Being righteous.

Right! And only because – what the problem – why people were so skeptical about Rasta was because they decided to live a natural life. They didn’t eat certain things –

[They have an] ital lifestyle?

Yeah. [And] I’m not gonna go to a barber and trim [my hair]; I have my locks, I’m just gonna grow my hair. I’m gonna go to the river and take a bath instead of using Babylon’s soap and whatever. And that was really the problem, because they [thought] these people are different – these people are crazy. [And then] the Rastaman is smoking weed. They think because he smoked this bush or this thing, he’s crazy. But little by little as I started to grow, and becoming accustomed [to the Rasta way of life], then I started learning more about what Rasta was. I still didn’t have any intention of being a Rasta because Rasta was – I grew up as a Catholic; so there was a slight little conflict going on with me. I can’t go do that you know. But then when I realized what was going on with the Catholic vibes, the Catholic church, and started hearing stories about them (laughing), I said wait a minute, you know? The Rasta vibes started feeling more appealing to me now, and I started to try to learn more. And it was Ras Michael – when I started to function around Ras Michael, that’s when I started to learn more. About Rastafari. Because then I started to play music with him.

When you’d play music with him, you’d talk about that? Because Ras Michael was one of the elders –

Yes!

So he was schooling you –

Right. And then you hear about Count Ossie and the Mystic Revelations of Rastafari – I started hearing the Rasta teaching. And then I realized these brothers are spiritual people. Because Rasta is a way of life. It’s not a look. It’s not a bunch of locks. Or how long your locks are. I realized that the Rastafari way is a way of living; the way you keep yourself, how you think, what you do, [and your entire] livity.

Now Santa, when you were interviewed on the Jake Feinberg show, you talked at length about the critical influence of African music and African drum patterns on your style of drumming.

Yes.

And you said that adding African elements to your rolls and fills helped to give you a unique sound. Was your interest and attraction to African drum patterns, and Africa generally, correlated to your [interest in and exposure] to Rastafari – and to Nyabinghi drumming?

You know what, man, along the way I was helped by a couple of great people. There was a brederin who also lived in America but he came back to Jamaica, I think his name was Teddy Powell. And he came back to Jamaica and opened a record store. And he used to go back and forth. And he would bring merchandise down; that’s when I started to buy American clothes because he use to bring a lot of American stuff; and he would sell it in Jamaica at his store. And also, he used to bring a lot of records. He’s the one that turned me on to jazz and African music.

Teddy Powell?

Yeah, I think his last name was “Powell.” And he played guitar, too. And he had a band. And I started playing music with him. He’s the one who opened me up to listening to African music. He said, listen to Babatunde Olatunji, [and] Osibisa. He had me listening to all the jazz players [like] Charlie Mingus, Coltrane, and Art Blakey – and that was not my school. Because I didn’t go to music school per se. That was my music school. He’s the one who turned me on to this whole polyrhythm thing. And then, for some weird reason, I felt a connection. I felt this deep connection like I was there. And I started loving it. I was like, wait a minute, I like that cross-rhythm thing. Because you know, we were just used to that “One, two, three, four.” But then I started to hear the [imitating African polyrhythm drum sounds]. It took me back to Africa. I started to go back in time. And I felt this connection, because I was like I’ve heard this before. Because you know we’re all connected?

Yeah.

We’re connected to Africa.

All of us, yeah.

So when [Teddy Powell] got me connected with [this] music, he got me reconnected with Africa. And there was this natural feeling that I felt. And then – everyone was playing drums – because of me listening to all of these African rhythms – it wasn’t even something that I planned – it automatically took me over.

When you’re onstage playing, [or] when you’re jamming?

Yeah. It was just something where I said, how best can I use some of that influence into what I’m doing?

You’ve often compared music to cooking, and using recipes –

(Laughing) Yes! Yes! Using recipes –

And I find that so appealing. Was the reaction around you [from] the guys who were playing with you – like [fellow legendary Soul Syndicate members] [guitarist] Tony Chin, [bassist] Fully Fullwood, [all the] guys you were playing with around that time in Jamaica, when you started experimenting with these African rhythms – were they all like, “that’s cool.” Or was there also a bit of, “Wow, what are you doing?”

Okay. So now, a lot of people didn’t get it. It was strange to a lot of people – [to] a lot of musicians. When I would do certain fills and because the fill wasn’t like a regular fill, that confused them. Because I was using polyrhythms that kinda influenced my fills. [And] for a moment, I had to kinda like pick my poison. Figure out who I can do it with. Because some musicians would get it, and some wouldn’t. ‘Cause the fills were kinda like complex; what I was doing. And I was still learning so, it might never have been all that perfect, but I was trying to execute it –

You were experimenting?

I was experimenting. And for a moment people were like, “Hmm, that foreign thing. That foreign kinda thing. Bro, just play a regular thing, man. Dem foreign thing – it throw me off.” (Laughing) So then I realized, okay, how can I simplify it, because maybe I was doing a little bit too much. So I said, okay, I didn’t take offense to what they were saying. I just had to go back to the drawing board and say, maybe I’m doing too much at certain points.

I think you’ve said before about drumming that [it’s critically important] to know when to play, but also when not to play.

Exactly. Because you don’t want to, [for every] bar, put a fill or a roll. You don’t want to be rolling every four bars, every eight bars, whatever.

There should be some silence worked in because –

Rhythms. This is the first time I’m gonna say this. This is something that’s been in me: I don’t like to do drum solos. I do drum solos, but I don’t really like to do drum solos. I like to be part of the happening. I like to be part of that movement where it’s not just about me. I want to be part of that. So I would do some wicked stuff, you know? (Laughing) If I’m playing, and I’m playing with good musicians who understand what is going on, that would inspire me. Things that you would normally do in a drum solo, I would put it in the music to make it musical. That’s me. I’m not knocking other drummers who do that. [But] for me, you know what, I want to be a part of the seasoning. It’s like you’re cooking and there’s too much black pepper. [Or] too much salt. I don’t want to overpower [with my drumming].

Now I understand you toured in Africa with Peter Tosh, and also with U-Roy. And in fact, Tony Chin has shared with me a picture of you in Africa; you’re holding a snake, and you’re looking kinda uncomfortable.

(Laughing) We did one tour in Swaziland. I wish we had done more.

That was with [Peter] Tosh?

Yeah. Because he was supposed to go to South Africa but that whole apartheid thing was going on, and you know [Tosh] was against that whole apartheid thing. Peter Tosh was the man. Because no one else was talking about it. Apartheid. I didn’t know what was apartheid. Peter Tosh is the first person I heard talking about apartheid. That was when I became aware of what was happening in South Africa. I learned all of that stuff from Peter.

Did the experience of visiting Africa, even if only for a spell – at various times, because like I said, I know you toured there also with U-Roy – did this influence you spiritually and musically [by] having this experience in Africa? Did being there in Africa – were you able to carry that back with you [and incorporate it] in all the music that you’ve [thereafter] played?

I felt like everything came full circle. At the time, I said, Africa, that I’ve been influenced by, now I’m right back in it. Now it felt right. Now I touched the dirt; I put my hand on the dirt. Now I can continue the journey. I’ve never spoken about this with anybody; so by you asking me it’s real cool. Because I can remember Swaziland, I was like, “Yes.” I was looking at mountains going up to the clouds; I was like “Yes, Africa.” I could see the sky blending with the mountains. And then, when I went back in ’84; ‘cause I went [in] ’83 with Peter [Tosh] to Swaziland, and then in ’84 I went back with U-Roy. And we [went to] Cameroon and Benin. And it was in Benin that I was holding that snake! (Laughing). This guy said, “This snake, it will bite you. But it won’t bite you if you don’t drop it. So do not drop this snake.” (Laughing)

(Laughing) I’m so happy you told me this story because there’s a picture of Tony [Chin] holding the snake, and Tony has a funny, big goofy smile –

Yeah!

And [meanwhile] you are [looking] like please don’t let this snake bite me.

Because it [was] a venomous snake. He said it was a venomous snake, but like docile. And then he put it in my hands, and it was warm. Its belly was warm. And then maybe [it] was enjoying my warmth, too. Then I said, “Take him.” (Laughing) It was fun though.

Now it was about [when you were] 16-17 years old, that you stopped playing with the Graduates and joined what would become the legendary Soul Syndicate – I think it was called the “Riddim Raiders” at first.

At first.

Now, of course, when I interviewed Tony Chin we talked about the formation and the earliest days of the Soul Syndicate. Tony said his friend Maurice Gregory was a singer but could also play guitar. And Fully [Fullwood] was also playing guitar. And they would sing together as a group on a street corner in Greenwich Farm. Now I know you grew up with Fully and your stepfather was friends and worked with Fully’s father.

Yeah. I think Fully’s father was [my stepfather’s] boss, or he was Fully’s father’s boss –

And they did welding together?

Yeah, they used to work at a company called Public Works Department. You know like how you have Caltrans [in California]; they fix the roads and bridges – it’s kinda like that.

But can you describe a little bit how you ended up becoming the drummer for Soul Syndicate? I know it’s been so long.

Ok, so I grew up with Fully. Because of the relationship between my stepdad and [Fully’s father]. And my mom became like a little – Fully and them became like the extended family I never had. So that was like a relationship that, because of my stepdad, now I have some other people and they became family. Fully’s mom, she was, she was, she was a mother. She was my momma, too, you know what I mean? And Fully’s dad was like, you know? So I became connected with them. So when my mom was going somewhere, she would leave me at Fully’s house, and I was taken care of. They would feed me, they would take care of me. You’ll hear Fully talk a lot about “I was his babysitter.” It’s true, you know what I mean. But that was the connection.

So Fully knew you already and you knew him when you were playing with the Graduates? And then how is it that you suddenly changed [bands]?

At first they knew that I was playing in the drum corps. Everybody used to say the “marching band.” So I was playing [those] type of drums. So I don’t think they had an idea that I started to do this next thing. I started to play a regular trap kit. So I was still [with] the Graduates at the time, but you know, it wasn’t going all that great because it was just one of those things where I could see that it wasn’t going anywhere. And I was growing. I was growing and I wanted to go somewhere. That’s just how destiny works, you know? It didn’t seem to me like it was going anywhere. But I was still young, so I wasn’t really worried, but I wanted opportunity. So it was one day, kinda like [in] the evening time, people were coming home from work – it [was] always excitement, I can remember that. So I was getting ready to go home. And back down East Avenue, and back home. And that [was] going toward Fully’s house. They lived on 9th Street. So I’m going down the street and this guy was walking up the street; he was a friend of the family. And he knew about the band. And he said to me, “Santa, Fully and them want a drummer, you know?” Because at the time Horsemouth was playing with them too, but they couldn’t get along with him. And then there was the next guy, Max Edwards. So they had a bunch of different drummers circling through. There was [also] another drummer named “Denny.” But he went into the corporate world because he was like an educated guy, so music was just a weekend thing. But they wanted a full-time drummer because Leroy –

So you literally heard [the Soul Syndicate] needed a drummer on the street?

Yeah, I was going home and somebody – I don’t remember his name but he was real familiar to me; I knew him and he knew me. And he said, “Santa, Fully and them want a drummer, you know?” Mi say, “Yeah?” Him say, “Yeah, man, they want a drummer, go check them.” I said, “Alright.” So I went down [there to Fully’s house]; I’m still part of the family. [And] at the time I was growing up, they knew I was in the drum corps, Fully’s dad knew I was in the drum corps. So I went there in the evening and said, “I hear you guys want a drummer.” And Fully’s father said: “You can’t play these kind of drums; you play marching drums – you don’t know about that type of thing there.” But he was just joking. He said, “You can’t play this type of drums here.” I said, “Okay.” So they started rehearsing at 6:30-7 at night. So the first song, the first song I played, there was this group called the Clarendonians, and they had a song, the name of the song was “Funny Man.” It was an up-tempo reggae song. And I was familiar with the song. And there was this anticipation. So I started playing the song. And everybody was like, wait a minute. All of the sudden the whole place caught fire. (Laughing). And then all Fully’s dad said – we called him “Mr. B” – he said, “Oh, you can really play this thing, man.” And that was it. I was the drummer ever since.

And was Tony [Chin] there at that time –

Oh yeah, yeah. Because Tony –

– and were you already familiar with Tony before that? Was that when [Tony] was living on Spanish Town Road?

Yes! He was not even a block away. He was just a few yards away from where I was right there. So I knew him. And Tony was a classy dresser, too, you know? (Laughing)

(Laughing) He still is! He still is!

Tony liked to dress up, and you know he has like an Elvis Presley kinda vibe. He was sharp back then, you know? But yeah, I was familiar with him. We weren’t “friends-friends,” but I used to see him and he always had his guitar. He’d always have his guitar, and that’s how it was.

In his interview with me Tony talked about how one thing that really helped the Soul Syndicate to get on its feet was when Fully’s father, Mr. B, he bought or he took over a loan of a bunch of musical equipment – guitars, amplifiers –

Yes, yes.

– from some shoemaker who had them, and I think he had seen you guys practicing – do you remember that – were you part of the group at that point?

Yes. Yes. You see what happened, Fully’s dad, he was the engine. He really loved the group. He was the engine that was pushing that thing. Because he knew that Fully loved music. He bought him a guitar. And then after that, I guess Fully liked the bass. So he got [Fully] a bass.

He really encouraged him?

Yeah. He started buying up all this equipment. And things that we couldn’t afford, he was like, “I can make this thing.” And he was a machinist. So he would make the cymbal stands. He could make stuff like that. He would make like the “drum throne,” you know, for the drum to sit on. You know it wasn’t the best, but it worked. Because a lot of times when we’d go places to play, you’d see groups play, you’d see a lot of groups with their nice, manicured stuff. We had some stuff (laughing) that came out of the Flintstone age. But it worked! (Laughing)

In an October interview with Mike Gormley for the Jeremiah Show, you said the first time you recorded with the Wailers – Bunny, Peter, and Bob – was at Dynamic Studios in 1971-72 –

Yeah, somewhere around there.

And you played on the hauntingly beautiful song, “High Tide or Low Tide?”

Yes, it was like a ballad.

I love that song. And you said that this was “even before The Wailers started growing locks.”

Yep.

What else do you remember about the first time you recorded with the Wailers? Was there anything about it that sticks out?

It was just part of a journey, you know. So it’s like this, I grew up listening to these brederins. From when they were with Studio One. When they were the “Wailing Wailers.” The three of them together, three powerhouses. So when Lee Scratch Perry – because Soul Syndicate – people never used to come for one person; they’d rather get the band. So people would come and they’d want the whole band. It was easier for them, you know? And we were tight because we rehearsed everyday like there was no tomorrow. We had that vibe together, so they wanted us as one group. So Lee Scratch Perry commissioned us and said come to the studio. And [when] I realized I was gonna be playing with the Wailing Wailers, I was like “wow.” I grew up listening to the brothers, you know what I mean!? (Laughing) So that in itself was like what you call a “culture shock” kinda. Surreal kinda.

[Because] you were playing with [people] who had been celebrities to you?

Yes.

Were you nervous?

Yeah, of course! Come on, man, you’re talking about the Wailing Wailers! These brederins, at the time, to me, they were established, because you couldn’t help but hear all of their songs in every sound system.

Now I understand the next session that you recorded with [the Wailers] after “High Tide or Low Tide,” was at Randy’s [Recording Studio in Kingston]?

Yes.

But that first session was also with Lee Scratch Perry –

Yes. Because at that time I think they had left Coxsone [Dodd] [and] Studio One, and “The Upsetter” [Lee Scratch Perry] was their producer.

Now apart from [The Wailers] being on the radio, and you could hear them wherever you went –

Well not much on the radio. More so on the sound system. Radio doesn’t want to play [reggae in Jamaica] –

And still doesn’t, really.

Nah.

And did Bob, or Peter, or Bunny, during that “High Tide or Low Tide” recording [session], did they say anything to you?

You know what? The thing about them, I was nervous, but I was nervous because of me. They were real cool. They were real, humble, decent brederin. And they weren’t like talkative people. They were reserved. Serious. That’s what got me, man. I was like, I better be on my “Ps and Qs” today, because I’m gonna be doing a session with the Wailing Wailers. But then, when I got in the studio with them, and realized how laid back they were – they weren’t barking out orders and trying to show that “we’re the Wailers,” they weren’t doing none of that – and after a while, they made me feel comfortable, because of their vibe. And from that day there was a lovefest with the Wailers, you know what I mean?

And Soul Syndicate?

Yes.

Now I mentioned how that next session that you were with them was at Randy’s Recording Studio in Kingston. And I know from interviewing Tony [Chin] that it was in that magical session, with again Lee Scratch Perry, that you played on the original “Sun Is Shining” –

Yes.

– and then you also played on the riddim that was going to be used for “Duppy Conqueror,” but was instead used for the hit song –

(Laughing) “Mr. Brown.”

Now already, to be candid, to be sitting with someone who recorded such famous songs that I love with the Wailers, it gives me chills, it gives me goosebumps, I mean, wow. But the thing is, in learning about your discography, I was really blown away also to learn that you were the drummer on Bob Marley’s song “Africa Unite” (on Bob’s ’79 “Survival” album), but then again, also, in 1980, [you played] on the song – that I love – “Coming in from the Cold” (on the “Uprising” album) –

Uh-huh.

– and then also, is it accurate that you played drums on the Bob Marley song “Chant Down Babylon,” the first song on the album “Confrontation,” released in 1983, posthumously, two years after Bob’s death?

Yes.

And is this all accurate when it comes to the songs you recorded with Bob [Marley]?

Yes.

Did I leave anything out?

No.

Can you describe the circumstances that led to your playing on “Africa Unite,” “Coming in From the Cold,” and “Chant Down Babylon,” all songs Bob recorded toward the end of his life, after he had been an international star already for a few years?

Well, “Africa Unite,” let’s start with that because that was the first one that I did at his studio, Tuff Gong, 56 Hope Road. So that day – because they used to rent the studio, too, you know? So I was at the studio that day to do a session with Burning Spear (Winston Rodney). So I was there, I got there, I always like to be early, you know? So I was at the studio, and Winston Rodney is supposed to be coming from Ocho Rios, so I’m there waiting. Well, Bob came and saw me and said, “Hey, what happened, who you work with today?” Mi say, “Mi work with Burning Spear,” and him say “Oh, okay, cool.” Typical Bob, him come out with a smile and a spliff or whatever and maybe a cup of tea or something, then he’d go to the back – to his space, you know? So, I’m there, waiting, waiting, waiting, and no Burning Spear. And he came around two times, after that, and the third time –

Bob did?

Yeah. ‘Cause it was his space; he was just moving around. So him come around and him say, “What happened, the man no come yet?” And time was [moving] on, and the studio was there. And him [Bob said], “What?! Musician there, and studio time a-burn. Let’s go mek some music. Make a song or whatever.” And we go inside of the studio. Apparently he had that song ready.

“Africa Unite!”

At the time he was getting ready to go to Zimbabwe. For the Independence [Day celebration]. They had invited him to come to do the independence thing for Zimbabwe. So I just happened to go inside the studio, and laid down “Africa Unite.”

Gosh!

So the engineer, his name was Alex Sampkins, he passed away a likkle while after that, but I went in, played the song, and I had to go back again. Because I played the song and the next day I went up there and Alex was like, “Santa, man, it’s kinda hard to tell you this . . . . We didn’t get the toms, man, the toms didn’t come out that well, but it was my fault.” He was saying something happened where the recording didn’t capture the toms the way they wanted to. So he said, “Can you overdub the toms?” Now this is the first time I [was] gonna be overdubbing on something I’d already played. Now you’re talking about trying to overdub a toms fill on top of what you[’ve] [already] played. So now you have to be thinking, okay, I have to make sure that I don’t overlap or play on top of something. So I have to listen to the song, and find that little gap. But I think what he did, [he] was smart enough, he said, “Listen, just do the fill from your snare”. Because they have the same settings. So, I would wait. I would listen to the song. The song played along in my head, and when that part [came], I’d do the fills.

Cool.

And that’s what happened. And if you’d listen to it, you would think all that was done one time. But the fills – all that [imitating drum sounds] – that was done after. (Laughing)

And did Bob work with you in terms of getting that right?

No, no, no. You see, what people don’t understand [is] Bob Marley wasn’t a person who’d hover over you. He was always the type of person who would allow you [to be yourself as a musician]. Like one time he and I [were] having a conversation. One night I was doing a session there [at Tuff Gong Studios] and it was late. And he came outside on the step and we were on the step talking. We were talking about life and what we were doing in life. And he was like: “Santa, you play drums you know? You play drums and I play guitar and sing. I can’t tell you how to play your drums you know, neither you can tell me how to play my guitar and sing. Because we do what we do. We have our own vibe that we work off of.” So, [Bob] was the type of person that [he would] allow you – I’m not saying he wouldn’t give you ideas. Like maybe, he wouldn’t say things. He would do things. Or just his aura – his vibe! And you would understand that [as the musician]. He wouldn’t even have to say [anything]. A spiritual energy is what Bob Marley had.

That is beautiful. And “Africa Unite” is such a classic song. Now with “Coming in from the Cold,” how did that transpire?

You ever hear the song Bob sings, “Natural Mystic?”

Yeah. “Blowing through the air.”

Yeah. That’s how it was, those [experiences I had with Bob], it was just natural mystic. Okay, so the day we did “Comin in from the Cold,” [it] was a mystic vibe. Because I didn’t go there [that day] to do that.

To Tuff Gong?

Right. I went there to work with someone else and I ended up working with Bob Marley. So now, “Coming in from the Cold,” I remember an incident that happened. And Bob was in exile for a while. He went out of the country. Now I didn’t even recall that. It was a few years ago, maybe two or three years ago, Neville Garrick was doing an interview. And then he actually said “Coming in from the Cold” was done when Bob had just returned back home. I was like, wow. So Bob was in the studio, and I went up to Tuff Gong; I was looking for somebody. So Bob was in the studio. And I mean, you know, no one would stop me from going in there. Anyone else, if it’s some stranger, you can’t go in there. So mi walk inside of the studio, and Bob and Tyrone [Downie] and Family Man, they were in the studio. I think they were trying to record [but] Carly wasn’t there. So I don’t know if Tyrone was playing drums or who – because Tyrone can play a little drums, too, yeah. Whatever was happening, I went inside the studio, and I was in the control room, and I looked inside through the window and Bob was sitting at an angle where he could see what was going on in the control room. So I came like I was looking for somebody in the studio, and he saw me. And him say, “Lock up the doors! Lock up the doors! Don’t let that man no go anywhere! Don’t make that man leave! Come inside here now.” (Laughing) Because he wanted a drummer. But you know they were gonna do their thing, because the thing with Bob Marley: he would use whatever resources he had at his disposal. Whether that be a rhythm box – it doesn’t matter. If Carly is not there or somebody is not there, he’s gonna make do. And of course, you can overdub. So he said, “Come inside here.” And I went inside the studio, and [Bob] started playing the guitar. Him play it one time, you know? And him say I’m going to come in after that. And remember, you know, there’s no rehearsal. Because Bob Marley was the type of person where it was just a vibe. And if you are in tune with that vibe, then it won’t be difficult for you. When you go inside the studio with a man like that, you have to leave all that ego stuff out[side] of the door. That was the thing working with Bob – you leave all that ego, all of that “me” stuff, you leave that outside. So Bob just show me what him going to do first, and then we just roll in. Him say, “You ready?” I said, “Yeah man.” And I sat around the drums. And the tape started rolling. And he started playing, and then I come in. One cut. Why [am] I’m telling you this – [that] it’s a one cut song? If I played it again, I would have done a different roll because that’s the way I am. It’s a magic. There’s a magic in the music. That’s where I come back to where Bob Marley would say “the natural mystic.” Nothing is planned. Everything is done – you do!

Nice. Now as best as you can recall, was it different or was Bob different when you recorded with him toward the end of his life, these songs that we’ve just been talking about – and I need to ask you about “Chant Down Babylon,” too –

It was all done the same day.

And then just later released?

Yeah.

But was Bob different, you know these were different times in his life then when you’d met him earlier and done “High Tide or Low Tide” and “Sun is Shining,” it [was] a very different time in Bob’s life, and in his career, and journey. You know, toward the end [of Bob’s life, when you played with him and] you did the songs “Coming in from the Cold” and so forth, was Bob, when you were with him, in the studio working with him, was there any difference [about] him? Being around him or the way he did music?

No, Bob was always evolving you know? He was always on that journey, you know? And it was always a mission, so for him personally there was no change. Because Bob, Bob had a commitment, you know? He had a commitment to what he was doing in life. That there was a mission. And you understand when you work with Bob Marley, you’re also on that mission with him. You’re also on that ride. When I remember the two times before I encountered with Bob, and then to come, and this was many years apart now, to come back again. In the 80s, not even thinking, Bob gonna leave us this soon. There was no thought of that in you. Because the journey continues even to this day –

And you didn’t know that he was sick then?

No, I didn’t. It’s after the whole thing – it’s kinda weird because, actually, I never [knew] that he had a foot problem. Because it’s not like now where you have social media. Everything was kept private, you know? “Yeah, Bob stub him toe, okay, fine.” It wasn’t like now with social media where somebody snitch. “Oh, guess what, so-and-so just sneezed. He caught a cold.” No, it wasn’t like that. So when I hear Bob passed away it was like a shock to me. Because I didn’t know of any illnesses or see anything, nothing like that.

Now, of course, because from roughly 1981 to his death in 1987, six years about, you toured, traveled, recorded with, and saw Peter Tosh – literally to the day he died – your connection to Peter Tosh is even deeper than with Bob Marley, true?

Yeah, because you know, I was more around Peter. I lived among Peter more than [with] Bob.

And because you were present when Peter was shot and killed, and you were also injured gravely in the incident, as well as due to several controversial statements, [even] accusations leveled at you, you’ve had to spend so much time discussing that terrible night that Tosh and Free-I and Wilton Brown were killed. And you’ve discussed this traumatic event many times, in many interviews, people can look –

Not at my wish.

– but people can locate these things if they want, and so I see no need to rehash this, unless perhaps maybe at a future meeting, when we have more time, and [if] you want to address further what I think are grotesque and shameful attacks on you concerning a very tragic situation in which you could have easily died, too. So maybe we’ll save it for another day?

No, no, no. One thing I need for you to have on tape: Okay. So this incident happened [on the] 11th of September, 1987. Now this lady, Marlene Brown, I think she did this interview – she went on Mutabaruka’s show. Because the first time I saw anything was [in] 2012. I was actually looking for something on YouTube, having no idea about this thing. I was here in California, [and] I was looking for something on YouTube. Maybe some music. Maybe some instructions about music – or something. And I saw this interview. And I said, Oh, Marlene Brown interviewed [by] Mutabaruka, okay, I’m gonna check it out and see what she [had] to say. And she was talking, talking, talking. And then she come to me now, and bro, I had to play back that spot. Over and over. Because I’m like, I’m not smoking no weed – I stopped smoking weed from 1990. I’m not drunk, nothing. So I said wait a minute, let me play this back. Did she really say that? And I played it back and I’m like, wow, wow. Okay. So now, what she said to Muta on the radio, to the world, big lie, okay, fine. Now all I would say to anybody, to all the people who took judgment on me from that time. Go back and watch her previous interview. There was an interview she did, you could see the interview, I think Dermot Hussey was the narrator. He was talking about what happened [during the robbery and killings], and then they were showing a picture of the house [while] Dermot Hussey was talking. And she was in the house. It could have been the next day. Because I was still in the hospital, bleeding, bleeding out. They were extracting all that blood. So I would say to everyone who is talking crap about me, go back and go to the archives. She did a couple of interviews before the Mutabaruka thing –

Where she never made this claim?

She never mentioned me. She was talking about everything!

And Santa, just for the sake of the interview, and because we haven’t said it yet, and so it can be clear when people read the interview, she made a claim on Mutabaruka’s show, and I don’t know where else she’s made the claim, that allegedly after the shooting, that she saw you and made a statement that, “Peter’s still alive. We can help him.” And you [allegedly], according to her, said “I’m not gonna help anyone,” [you got] in your jeep, and [went] to the hospital. Now as I’ve said, I think it’s a shame and a terrible thing for someone to say these things. You had a collapsed lung, you had internal bleeding, you literally fell into the hands of the attending [medical personnel]. [And] my understanding is also that Peter Tosh had been brutally pistol-whipped. He’d been shot in the head twice. That to say that he would have survived is to be making all kinds of claims and speculation without medical training or anything. And, also, to cast judgment on a person in a volatile situation, a violent situation, I find it to be… disgusting.

Yeah, and –

And I feel badly for you. I would say, as a Peter Tosh fan, and [from] what I understand, that I cannot believe that Peter Tosh, if he were alive – I think he would find this to be a revolting situation, that you should have to deal with this accusation.

Of course, of course. You see, here’s the thing, she [went] on this program. I don’t know why she did that. Because number one, me and this woman we never had a problem. Whenever I would go to that house, I showed respect to her. Neither she nor I, or me and Peter, had any problems. So there was no issue where, oh, they owed me money, or they prevented me from anything. We had no problem. We were just in a situation where a terrible, terrible thing happened. Now a lot of people got shot. Three people died. I was the most critical [out of the survivors]. Now she and I, we both got up at the same time. And the first thing she said to me, “Are you okay?” I said, “No, I’m shot, I don’t feel right.” Because by then my body started getting weak, and then my breathing became weird. Breathing was like a struggle.

You were probably in shock, too?

I was in shock! Look here, I’m a human being. I was shocked, and I was scared, you know this was like something I’d never dealt with before. This is not just me bumping my head on a door jamb or something. This is a bullet. And I realized that something was wrong because my left side was numb – I couldn’t feel that. And the only conversation me and this woman [had]: She said, “Are you alright?” I said, “No, Mi get shot, and mi nah feel right.” She said, “Okay, alright.” I said, “Look, mi a-go to the hospital.” She said, “Yeah, no worries, no worries, mi a-call the neighbor.” That was the last conversation me have with her. And me go outside [to] my vehicle. Struggle with the last likkle breath, or last likkle energy or adrenaline, my brethren. Drove myself to the hospital. How I did that? I don’t know. Because even the people the next day, the nurses dem I heard them having a conversation. Them say, “Oh, I heard one of the patients drove himself to the hospital. I wonder who that was?” And I said, “That would be me.” She said, “No, Mr. Davis. There is no way you could have driven yourself here in the condition you were in.” I said, “It was me.” She said, “Come on. I was here when you came here last night; you couldn’t have driven yourself in the condition that you were [in].” I’m like, “What?!” Now, [Marlene Brown’s] going to [go and] tell people on the Mutabaruka show, for whatever reason, I don’t know – maybe she had something in her heart against me for a long time. Because me and Peter, me and Peter had a good relationship. So a lot of times I would just, unannounced, go check Peter. Because back in [those] days, you [didn’t] have cell phones and all dem things. So you go check your brederin [to see] if he’s there, yeah; if he’s not there, you come back again the next day. That’s how we used to do it. So a lot of times I would go check Peter, and of course she’s there, and Peter would be like, “Mi just call you, you know.” Like a telepathic kinda thing. I said, “Mi feel your vibe, and [so] mi come check my brederin.” Because I worked in his band; I was his drummer. So I would just go check him periodically – no problem!

And you never sensed a problem with Marlene Brown? And to this day you don’t know why she’s [making] these [accusations]?

I have no idea why she would do that. And she’s gonna tell the world that she – now listen to where the whole thing go south now. She never remembered that I was in the house until she hears my jeep start up. And she ran outside, according to her, telling me that Peter is alive, and he can be saved. And my response to her was, “Mi get shot, and mi nah help nobody.” Now, even if I would have responded to her and [said] “[I’m] not helping anybody, that doesn’t mean like it seems like I can, or could. But I just don’t want to be involved – that’s the way it would sound by putting it out there like that. Because if that conversation had [actually] taken place, I wouldn’t have responded like that. My response would maybe be: “Sister Marlene, I’m not in no condition – I’m dying.”

I feel badly that you have to deal with this situation and respond to it publicly. Over and over. And I knew that even coming here, because it’s become such a thing, it’s something that someone who interviews you feels that they have to ask you about – um, but I’m glad that you [are] at least able to say what you feel inside [about it]. And one thing that’s powerful, all the people who [were] Peter Tosh’s friends and colleagues throughout the world, they are all still very close with you – they see you, they tour [with you], they don’t have these malicious thoughts. And they haven’t been moved in any way by this – this – gossip.

My brother, a gunshot victim, anyone who’s been shot, will tell you. People get shot in their leg and they die. They bleed out. People get shot in their arm and they bleed out. It just depends on if that artery gets severed, you know what I mean?

You’re blessed. You don’t have to convince me because –

Bro, I’m left with a bullet still in me right now.

In your clavicle?

Well, it went down in my shoulder. Let me tell you this: A lot of people don’t realize what happened, you know? It was just the angels guiding me. Because if that bullet had gone straight through flesh, I wouldn’t be here talking to you today. It would have hit all those major organs inside of me. It hit – it broke my clavicle.

And I heard you didn’t [learn] this until [much] later on?

Yeah. I was doing a show with Wailing Souls out in Monterey, [and] I went to do a crash on my cymbals, with my left hand. And I felt this sharp pain in my shoulder. And the pain was [so] excruciating, I wondered if I broke something. Didn’t even think it had any connection [to when I was shot]. Only to find out when I did the x-ray and the doctor was like, “Did you get in an accident or something?” And I was like, “No.” [And he said,] “Did you know that your clavicle was broken?” I said, “No.” And then he saw the bullet. And he said, “Is that a bullet?” And I said, “Yeah.” Then we started talking and he looks again at the x-ray and he saw like a little dent on [my clavicle]. And that’s when I realized, Oh, the reason why I’m still here – that’s what happened, the bullet hit [my] clavicle and turned, that’s why it ended up in my back area. If it had gone straight down, it would have shattered my lungs and everything. And the [doctor] said, “Your clavicle [was] broken, and it healed back in place.” And what happened is it must have been a little out [of joint], and I irritated it. All these years later. So, what I’m trying to say to people, is before you start to judge, go and understand the whole thing. [And] I would say to all these people, if what [Marlene Brown’s] saying – because remember when an incident happens, there are certain details you don’t forget. It’s there! Like I can tell you everything [that happened] from the moment it started to the end.

Like in slow motion?

Yeah. I can tell you everything that happened in the order it happened [in]. Because I was there. If what she’s telling the public about me, [and] my involvement and what I did, if that had happened, [that] first set of interviews that she did, that would be something on the top of her brain. Like, oh, you know, “Out of all the things that happened, I can’t believe that Santa Davis would do such a thing, blah, blah, blah. So I would say to people, she – I’ve seen like about two interviews [she did]; one where she was in the house with “Mikey,” the other brother, with his head [in] a bandage. And they were talking about the incident. And neither she, nor him, they didn’t mention my name one time. They didn’t even mention my name. And if that had happened – come on! I saw two interviews [Marlene Brown] did [in the immediate aftermath of the shooting]. Not one time did she mention me by name.

And I’m glad you at least have a chance to let folks know this. [And then that] guy went and made a whole thirty-minute [YouTube] video screed.

Yes! This one guy. Based off of what he heard. And the interview with that lady on the Mutabaruka show. And I’m like, dude, wouldn’t it be man enough to try and find me and just have a talk instead of just – putting my name out there like that? Hey, look here, I’m a human being bro, first. I’m a human being. I get scared like everybody else. And if you have never been in a scary situation before, then you can’t talk to the guy who’s been there. You know, I couldn’t go and discuss Vietnam or Iraq with an Iraq veteran. I couldn’t say, “Oh, really, I know what happened”; I don’t. I can’t explain that to nobody. I can’t compete with the guy who was there. You see what I’m saying?

And you have been so candid. I’ve watched many of the interviews you’ve done. You’ve gone on so many different programs and shows – live on TV, in fact.

Yeah.

Winford Winslow [and] other places [like] “I Never Knew TV,” other stuff which people can find. And you’ve been so straightforward with everything that happened in that incident: how they came in; all the things that I don’t really want to get into. Because I find that it’s unfair even that you [should have] to do that. Because these are traumatic things. You know I was a criminal defense lawyer before I started to write and to invest time into reggae music like I have the last few years. What I did was I did criminal defense work. So I’ve been around and had to learn about a lot of heavy situations. With people being confronted with violence and being the victims of violence.

Yes. Yes.

And like you say, people who haven’t been there should never talk about the situation; and people who have been there, and people who have some worldly sense about things, know better than to make assumptions based on controversial things that I know began really with what Marlene Brown, Peter Tosh’s common law wife said on the [Mutaburaka] program. And folks can judge for themselves if that has any merit after they go and listen to what you’ve said about the situation.

Yeah. But then this guy that did the YouTube thing, I mean, you know what, it’s unfortunate for him. Because you know what bro, I don’t hate that dude. I don’t. Because I can’t give myself – I don’t want to waste energy. No, I don’t hate that dude. It’s very unfortunate. For him to hear something like that, [and] for this guy to say some stuff about me, I’m like, wow, really dude? You didn’t even try to get in touch with me. Face me! And this guy said some of the most vile –

I know. And I felt bad [watching it]. It’s [so] wrong.

I heard it and was like, should I get angry? Should I respond? A lot of my friends were like, you don’t have to explain – bro, I bought a go pro camera.

Yeah?

And I sat in this room –

Oh no, you were gonna film a whole response –

Bro, I filled up a bunch of little [recording cassettes].

You were so angry probably.

No, no, not really angry. I was upset, but not really upset. I was just trying – because I was gonna do my piece and put it out there. But not cursing anybody. I wasn’t going to clap back and call him names. And then my wife was like, “You don’t have to do that.” And a lot of my friends were like, “You don’t have to explain anything to nobody.”

I’m glad you that you made that decision.

I’m glad, too. Because it would seem like, oh, you tried to explain your way out of something or whatever. I’m not trying to explain my way out of something. Any individual, any human being, you get shot – I’m still walking with that damn thing inside of my body. You think I volunteered for that? (Laughing)

Santa, for weeks before coming here – for weeks before coming to your house – I mean I have been talking to my wife, hey, I’m going to interview Santa Davis; my wife knows when I do interviews; and I told her – I don’t think I’m going to even ask him at all; I don’t want to ask him at all about this because I just don’t want to give it any attention. And I feel terrible to even ask you about this. I can’t believe this exists – this [YouTube] video, and then everyone said to me: Yeah, don’t. But then at the same time, because it’s out there – I’m glad we’re at least able to at least let you say this, and later, when we meet again, because I think we’ll need to –

Yeah, of course.

– if it occurs to you that you want to say more about it, feel free. Now with your connection to Tosh, and all these good years that you had with him – touring with him, being with the brother every day, for six years, and recording some of the world’s most famous, revolutionary music that there is – when you think of Peter Tosh, and you think about the time that you had with him and the memories, the records, the hit songs, when you think of Peter Tosh, what is the immediate memory, what’s the thing that comes immediately to your mind when you think of the brother? Whether it’s about his music, or a time that you spent with him, or just a vibe or feeling – what was it like to be with a guy like that, to be so involved with him? What is it that you think about when you think of him?

(Laughing) Well, you know what I think about Peter? How much of a brother he was to me, the brother I never had. How much of a human being he was. How intelligent that man was. How concerned he was about the plight of people who couldn’t help themselves. Who didn’t have a voice. And he felt the responsibility of taking that mantle, you know? He was concerned enough to put his life on the line. He was a revolutionary. He was a man who – people don’t know, but Peter was a reader. He used to read a lot. He was very in-tune with what was happening. He wasn’t a man who just sat around smoking weed, and just getting high and whatever. He was a thinker.

He had a lot of substance to him.

He had a lot of substance.

You can tell from the music.

And he was a people person. Peter was a human being. Peter was a man who, you know, a lot of times – Peter Tosh would tell me personal things about his life. About things I wouldn’t tell [anybody] – I keep that (clutching chest).

Respect.

Peter Tosh told me things I don’t know if him tell his own children, but that he would tell me. Personal. Me and him would sit down because we kinda share the same kinda thing. The same kinda vibe. Of growing up a certain way. And he was my big brother. Peter Tosh – from the first time I met that brethren to the time he passed away, we never had a bad situation between us ever. There wasn’t any kinda grievous anger or whatever between he and I. So what I can remember about Peter, Peter was a good human being. Who was taken away –

Too early?

Too early. Yeah and the people who took him away, they are the ones he was looking out for. They are the ones he was fighting for.

Now I’m unsure of the date but you were interviewed for Sabian.com, a maker of cymbals –

Uh-huh, I’m endorsing them, too.

And in that interview you said that the favorite album that you’ve played on is “Mama Africa” by Peter Tosh.

Yes.

And it seems silly to ask you, because that “Mama Africa” album is so good and unquestionably a classic, but why is that particular album – out of all the thousands you’ve played on – why is that one your favorite?

Because I felt I was allowed to be involved in something good. Because Peter, Peter was just like Bob, you know? Peter was very musical. He was a good musician. He could play the guitar. He could do all these things. But Peter allowed us, each and every one of us musicians, to take charge.

Of your own space? And your own talent?

And of the music.

Wow. Yeah.

We were in the studio and it’s his song – it’s his song. But he would sing the song, whatever. We get the structure of the song. And then we’d be like, “Ok Peter, cool out a likkle bit, bro. We’re gonna work with the song.” And he didn’t say anything. He’d just go sit down in a corner. Smoking his spliff. And we were there, just working out the song. And he trusted us. Because he knew that we were doing it in his best interests.

Awesome.

So he allowed us to be involved. You see what I’m saying?