[:en]

Shashamane Land

Interview by Matthew Jones

Coming off the back of their most successful album to date in Songs Of Praise and establishing themselves as a popular fixture on the festival circuit, anticipation was high for In Pursuit Of ShashamaneLand. Identifiably unique as ‘African Head Charge music’, the sound evolved once more to connect with the popularity of ‘global fusion’ within club culture. This placed the band in a context where you were as likely to hear their tunes being spun at a night such as Megadog or Whirl-y-gig as booming out of a dub soundsystem, or mixed in with the tribal trance sounds of Psychick Warriors Ov Gaia or Transglobal Underground. In summer 2018 we sat down with the band’s leader Bonjo Iyabinghi Noah to discuss this period in The African Head Charge story.

I wanted to ask you about the title In Pursuit of Shashamane Land, that’s a reference to the Rastafarian settlement in Ethiopia?

Yes, I mean, l’ve made that transition [(rom Jamaica to Africa]! For 23 years now l ‘ve been living in Ghana. For me when you say ‘Shashamane Land’ that’s not just Ethiopia that’s the whole o Africa, it’s just that Ethiopia is the main peak, like the capitai of the whole of Africa, for us. So ‘In Pursuit’ means ‘returning my spirit to my spiritual home’. That’s what it’s ali about.

This album also contains some of your most melodie work, there are these really nice harmonies on it, and in places it feels closer to your other group, Noah House 0f Dread. What are the differences between Noah House of Dread and African Head Charge?

I think Noah House Of Dread is more deep roots reggae music, because that’s something that’s in me naturally, you know, as a Jamaican we have that music in us. African Head Charge is different, it’s a fusion of different kinds of things, but NHOD is more straight reggae, like you have Burning Spear, or Culture, of those kind of artists.

In addition to the rhythm section of Peny Melius and Wayne Nunes, who form part of the modem day African Head Charge line-up, I wanted to ask you about Skip McDonald’s rote in this record.

Well l’ll tell you, when you mention Skip, I would say he’s the greatest musician that l’ve worked with. l’ve worked with lots of great musicians, but he is the number one: top, top, top. We are so lucky to have Skip in the On-U Sound thing. He is the number one. I mean, I rate guitarists – like the kings, Hendrix l’m mad about, but we can’t put no one near Hendrix – but Skip is one of the greats. I don’t think people have seen the best of Skip. I value him more than anyone else in my career. If you ask me, say if I’m gonna do an album, who l’m gonna cali first, l’m calling Skip.

He seems to have contributed quite a lot to this period of African Head Charge.

Me and Skip, we can it down and make an album in a week. Skip is brilliant because I know he respects me. True combination of me and Skip and Adrian was very close, he respects me. The only disappointrnent I had is that I think Skip should have been the main person for On-U Sound. Anything that’s come from OnSound, Skip was somewhere in there because he knows the ins and outs of everything, when it comes to music.

Those albums, especially Shashamane and Vìsion of a Psychedelic Africa, most of the arranging is done by Skip. He ‘s somebody that I can go to with some lyrics – because normally when I have lyrics I have the music in my head as well – and I can just sing it to him and he’ll sit down and work it out. What he puts to it is magie.

You were continuing to tour when this album carne out, but then the live side seemed to go quiet later in the 90s?

You know me, I enjoy touring. I really love it, because I enjoy seeing the people and enjoying the people, and things like that., ‘No matter the ups and downs – because for me, that’s !ife, we must have ups and downs – I always try and enjoy it, because !ife is short. My motto is “always enjoy” – enjoy dancing, enjoy singing, enjoy music, enjoy each other. That is what my !ife is all about. I love being at festivals, I love being at clubs. ECl was the agent that I started with, but the guy sold it to some people, and they told me that they’d gone to a more guitar band kind of things, so I lost that agent, and it hasn’t been so good since. I want to go back touring again but at the same time, I have my family in Africa. For 23 years now, l’ve been going there, my children are there. When I talk about In Pursuit of Shashamane land, anything I say, l’m serious about. Some people talk about going back to Africa, sing it, but they don’t do it. Me – anything I say or sing l’m serious. So that’s why I ended up going to Ghana, and I just love it there.

SONGS OF PRAISE

Interview by Matthew Jones

By the late 1980s African Head Charge had existed in some form or other since 1981 and had become one of the most established and well-loved artists on the On-U Sound label, particularly once they moved out of the studio and became a live act, sharing stages with an eclectic range of acts from anarcho-punks Flux Of Pink lndians to more dub reggae oriented bills. When it carne to making records, the project was (and continues to be right up to the present day) a joint creative venture between Adrian Maxwell Sherwood and Jamaican-born percussionist Banjo lyabinghi Noah. In summer 2018 we sat down with Banjo to discuss this period in the African Head Charge story.

Perhaps more so than your earlier records which are quite instrumental and psychedelic, Songs Of Praise feels connected to a lot of the things you’ve mentioned about your upbringing with the introduction of more vocals and spiritual chants. Was it a conscious decision to move the sound more in that direction?

That was conscious, that was something we wanted to do. Different voices from different ways of worship, or different ways of celebrating lite. You find the Ras’s, we have a different way of expressing ourselves, that’s why I called it Songs of Praise, from all corners of the earth. Whether you’re a monk or Sheikh or whatever – who likes to ‘get in there’ and do something, be a part of it – that’s what Songs Of Praise was ali about really. AII the religions can do something with the music. That’s why Song Of Praise is more or less my favorite album.

I think it’s a tot of fans’ favourite as well. Do you have any thoughts about why people feel so connected to this record – is it the spiritual aspect?

I think so. Because sometimes you do things and you don’t even know why – I think they feel something in it, everyone no matter what race or religion or whatever you are. That’s what that album is all about, it’s got nothing to do with the individuai, it’s to do with the whole world.

You recorded some of this at The Manor, famously Richard Branson’s piace …

Yeah that was stepping up! From doing the earlier records in places like Berry Street and Southern, that’s a big step! Adrian knew how to get deals. Go in at night or find out that the studio is not booked tor two weeks so he could get it tor half price or whatever.

You’ve mentioned that recording with African Head Charge always starts with layering of the rhythms. How did you approach arranging them? How did you approach arranging the new element of vocal parts around that on this record?

Yeah, see what Adrian does – there’s this guy called Alan Lomax, and he went to Africa and got a lot of chanting. Adrian had a lot of them. We would sit down and listen to them, and see which one would suit which rhythm, then mix the sampled stuff with live singing that we would overdub on top, so that part of it is kind of layered as well.

I wanted to ask you about a guy that played on this record and sadly passed away recently, Sonny Akpan.

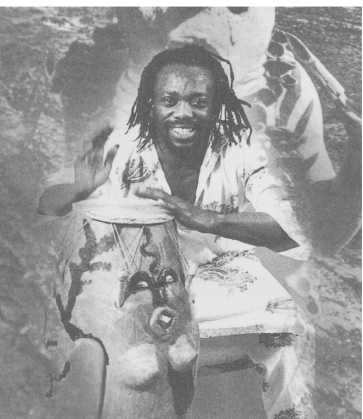

Yes! I would say Sonny was my teacher! Let me explain to you how I met Sonny. When I was starting out in music I used to go tor auditions tor anything. One day I saw in the newspaper that a band from Africa were auditioning tor a conga player. At that time I was still learning, but I thought l’d go, so I went and met Sonny and his band The Funkees. I found that I was the only Jamaican in the band, everybody else was from Nigeria. They were ali speaking their language, so I was quiet, whatever Sonny told me to play I played it. I think one of my strengths is to maintain a pulse, I can maintain a pulse for an hour if I have to because l’m trained that way from Jamaica, that’s how we’re taught. Even with the lndians, they played the same pulse tor three miles, and three miles coming back [referring back to the Hosay commemorations he witnessed growing up in Jamaica]. When Sonny gave you a rhythm like [sings drum pattern]then you have to play that tor one hour, nothing else. Most people want to add things or this or that, but me I’lll hold that, I maintain the pulse unti! it becomes hypnotic. Sonny was such a great teacher and great player, he started working with top people like Eddy Grant. I think when the Eddy Grant thing finished that’s when he carne and started working with me as part of African Head Charge.

Did Sonny used to play with you live around that time?

Oh yes, most of the time, if you were at an African Head Charge gig and saw a little short man, that was Sonny Akpan. When we did Glastonbury – twice we did Glas onbury – you’d see Sonny. We had the keyboard player from Eddy Grant playing with us as well.

I wanted to ask you about how the live appearances evolved, because initially African Head Charge had been more of a studio project.

So I used to do workshops, going into schools with ali the children around me with their percussion and everybody playing. The schools used to pay me to do that and I used to love it. My brother was in Austria and they were playing “My Lite In A Ho/e In The Ground” in this piace, and they were liking it. And my brother Baron looked at it and there was a small picture of me on it. He said “Hey, that’s my brother” and they said to him, “That’s your brother? Could we invite him to Austria?” So we organised to go to Austria to do a weekend thing for the Friday, Saturday and Sunday in this back yard. , It was a place where people go to drink and eat, but they have a back yard as well. We went and set up a stage and played there for three days. I didn’t make a penny. I ended up losing money because I took too many people. l’m like that. In those days, I used to organise everything for African Head Charge- posters, everything. I brought [toAustria] the Rasta drumming, I brought Bim Sherman, I brought Noah House Of Dread, I brought African Head Charge. I brought about eighteen people, we were overloaded really. There was no nooey left! I just wanted to do something big, you know, so we did it. That’s the first time I thought, “Wow, it’s çool to take this out on the road”.

When I carne back, they asked us to do the University of London, ULU. lt sold out! I never knew so many people were willing to turn up to African Head Charge! After that, I started to pròmote shows myself. l’d go to the venue and ask if we could play there, and l’d take a percentage. I put on a show in this piace and it was a flop! Nobody turned up. We put posters all over the place. But this man Vince Power was there, it was him that really kickstarted the live thing properly. Maybe he didn’t know what he was doing. He carne and he gave me a card and said, “Bonjo, I like what you’re try to do, come and see me at this piace”. So I went and saw him at the Mean Fiddler and we sat down and talked, and we put on a show there. He told me about this small club called the Powerhaus in Angel. So I used to go there once a month and put on a show. I liked it cos it’s good when it’s small and it ram out. So we were playing there once a month and a woman carne there and saw the thing and she liked it. She started talking saying, “I know somebody who knows somebody who knows Glastonbury, and I can ge you on it.” So wow, she got me on there. I remember they paid me 1000 pounds for Glastonbury. I got a coach that cost nearly 400! Because I wanted to go to Glastonbury nice, you know? I got some good musicians and went to Glastonbury.

Also, we did a song, which I’ll put down to Adrian rea:ly, it was him that really carne with the idea. We did a riddim and he decided, “Let’s put Einstein on the track” (editors note: “Language & Mentality” from the 1986 LP 0ft The Beaten Track). Somehow, because of that, the students ali over London start liking us. So we started to gig ali over London. lt wasn’t paing much money but it was régular, in different student unions.

There seems to have been a strong culture within the label of people contributing to each other’s music.

To me, it was a family. Everybody has got their ideas. If Bim Sherman wanted to do something then he called me and I went and contributed my best towards on it, and l’d get that in return from other musicians we invited to play on my records. Obviously we’d get paid, but that’s what it was. lf Gary Clail’s doing something and he feels like Bonjo can do something that makes it better, then so it is. For me, it’s up to you to make an effort with what your individuai thing I don’t sit back and wait for people to do things for me. l’m the type of person to go find a little pub down the road and say, “Listen, I want to come here and show you people what I am.” When we did the show in Brixton at The Fridge, there were three floors and it was me that organised the whole thing. I brought the whole of the On-U Sound people together – Gary Clail, Mark Stewart, Bim Sherman. I had the Nyabinghi drumming downstairs and I had the sound system in the middle, and then at the top we had sormething else.

Finally l’ve got to ask about something you made just before Songs Of Praise, the highly unexpected cover of the Neighbours theme (as Noah House Of Dread) !

Yes, the Neighbours thing … we were going through stress! You know, everybody in I ife goes through a few things. Either you’re gonna come out strong or it weakens you and turns you on to alcohol or drugs or whatever. I was going through a rough time – I think that’s when me and my wife separated. She had the children, so l’m on my own and I was getting sick and nothing was happening with the music side of things. I decided, “l’rn not gonna go down”, because have that pride about me. I’ll stay strong and be up there. So I decided to stop – don’t drink, don’t smoke too much (have a little bit sometimes) – but get up every morning and go jogging! When l’d get back, there was this programme on called Neighbours. I was young in those days and I really did have a love for Kylie Minogue! l’ve grown out of that now, it’s a long time ago! When Neighbours would come on, that was the time I was stretching. I used to go and sit in front of it and do my stretching for twenty minutes. Even now I still like stretching. I was stretching to that programme and I heard the song, “Neighbours, everybody needs good neighbours”, so I said, “Hey, l’m gonna record a version of it”. I called some people together – some of them I couldn’t pay, I told them l’d pay them after – and I went and did it. Then I got a cali from Go! Beat that Norman Coo was signed to, and they gave me some money.

lt was the first time I got so much money in my life! I can’t remember how much it was, but it was a lot. lt paid off my rent arrears and instead of driving a banger, I got myself a reasonable car. Then Radio 1 started to play it, everywhere started playing it. But Tony Hatch wrote a letter to those people – that’s what thèy told me anyway – that we couldn’t release it properly, because he’s the songwriter, but by then they gave me the money already! So I sorted my life out. I ended up buying a flat, started working in the schools and things and started to look up. They sent me to work with Norman Cook too. I did a single with him called [singing] “The More We Are Together”. I wish I could find it. He had a studio in Brighton somewhere. After that I lost touch with him, and then I found out he changed his name to Fatboy Slim. I should really try and get in touch with him, see if he’d remember me!

VOODOO At THE GODSEND

Interview by Matthew Jones

In summer 2018 we sat down with Bonjo to talk about the record:

So Voodoo of the Godsent is the most recent AHC album to date. What can you teli me about the process of making that?

We did that record in Ramsgate, down at Adrian’s house. I think the next album we’ll do there as well. lt’s good, I can go there spend a few days there, wake up in the morning, straight in the studio, work until the night, stop when we want to, do anything you know? So that’s the good thing about him being up there, lots of creativity, we have time to do plenty things.

George 0ban provides some beautiful basslines …

Yes, the originai Aswad bass player, he’s something else. Whenever Adrian can get him to do a session he’ll do it. lt’s the same thing with people like ‘Blackbeard’ (Dennis Bovell). Any time players of that quality are available to do something, then we’ll try and get them.

On ”Take Heed and Smoke Up Your Colly Weed” there·s a sample of Prince Far I. which completes the circle of when you started working with Adrian with Creati on Rebel. What are your memories of Far I?

When I look at Prince Far I, it reminds me of one of these great prophets in the bible! When you see the way he dresses, everything about him, like if he carne in this room you’d feel as if one of the greats has come in.To me he wasn’t like a normai person -out of ali the musicians l’ve known, Prince Far I, Lee Perry … they’re not normai. When I say ‘not normai’ I don’t mean it in a bad way, it’s more like they’re something else. You read about Matthew, Mark, John, Luke – ali these disciples, that’s how I felt when Prince Far I walked in the room. He had a presence, the voice, everything. To me that was a big loss, tragic (Ed’s note, Prince Far I was shot and killed in September 1983). lt freaked Adrian out, l’m teliing you that was a knock-out blow for him. When it comes to people – I think Prince Far I is the number one for Adrian.

I remember the first time I met him, I had a band called Fusion. We had a gig at The Music Machine in Camden Town (editor’s note, stil/ standing, it was later renamed the Camden Palace and now called Koko). The bill was Prince Far I as the headliner, Fusion, and Generation X (with Biliy ldol)! Generation X went and did their show, we went as Fusion and did our show, then we’re in the dressing room and we saw Prince Far I walk in and say “Who can play Satta Massagana?!”. I said “Yeah man we know them tune there man”, and he goes “right you’re playing with me” – he’s the top of the bili and he carne without a band! So we all sat down, learn the things, then out on stage! That was our first time meeting Prince Far I and we did the gig there and then. The only problem was we were arguing about money! We knew he needed us so we stuck to what we wanted, because if we didn’t do it he had no one, so we decided to stick to get the extra 1 pound or whatever.

You were very prolific in the 80, releasing lots of records. then it slowed down a bit. Was that partly through prioritising family and being a father and your life in Ghana?

A lot of changes happened in the music business, big changes happened. We were selling a lot of records unti! everyone started downloading, then I saw there was a big change. Even the distributor went bankrupt! That was a big fuck up for us, because we were owed a lot of money. That fucked Adrian up too, because most of the money was his investment. That was when the whole thing started to go down. Alright, we must have money because we have children to look after, but for me, it was just the music. I love playing music and I love performing live. One reason why we love to play live is because we see the people’s faces and they love it. We see the feeling of the people and that’s what keeps me going, because I see that people them like it .When we’re backstage getting ready to go on, you feel the vibes of the people them, knowing that they’re gonna have a good time. l’m a pensioner now , I could go to Ghana and just relax, it’s like heaven there. But one of the reason why I come here, every year, and spend three or four months is because I can see the people love what we’re doing. They love it. lf I didn’t feel that they love it, I’d stay in Ghana and enjoy the rest of my life there.

Looking at some recent footage of you, the audience is very diverse. it’s ali ages!

Yes! l’m surprised as well. When I look out, I see young peop e. l’m expecting to see people in their 40s and 50s and that, but l’m seeing people in their 20s. I couldn’t believe it.

What’s an average day in the life of Bonjo like?

What I love to do in Ghana or in London, first thing when I get up, is go and do some training, keeping fit. l’m addicted to training. I like to go o e gym for at least two hours every day. Then I feel better for the rest of the day. After that, anything can happen. When l’m in Ghana, I do the same thing. I jus go tram, come back, and just enjoy life. l’m just enjoying my lite. Seriously!

Do you have family in the UK as well?

Yes I have some big children here from my first marriage. most of them in London but some of them are spread out – some in Nottingham, one of them’s got married and gone to live in America. l’ve got more children ìn Africa. Somehow God has blessed me with eleven children, and I think I want some more. So l’m gomg back to see what’s going to happen.

What’s the future of African Head Charge? Can you teli us about the new record and your life plans?

I will always keep making records, and because l’ve go s g with Adrian and Skip, we can do a lot of things. So we’II keep doing that, that’s a good combination. And once there’s a good combination, you should keep , especially on the recording side of things. I love to do live things as well, I love to do the ciubs and the festivals. One of the reasons why I love the clubs is that althoug the clubs doesn’t pay me as much as the festivals, you can actually touch people, they are very close to you. lt’s like having a big party! [:]