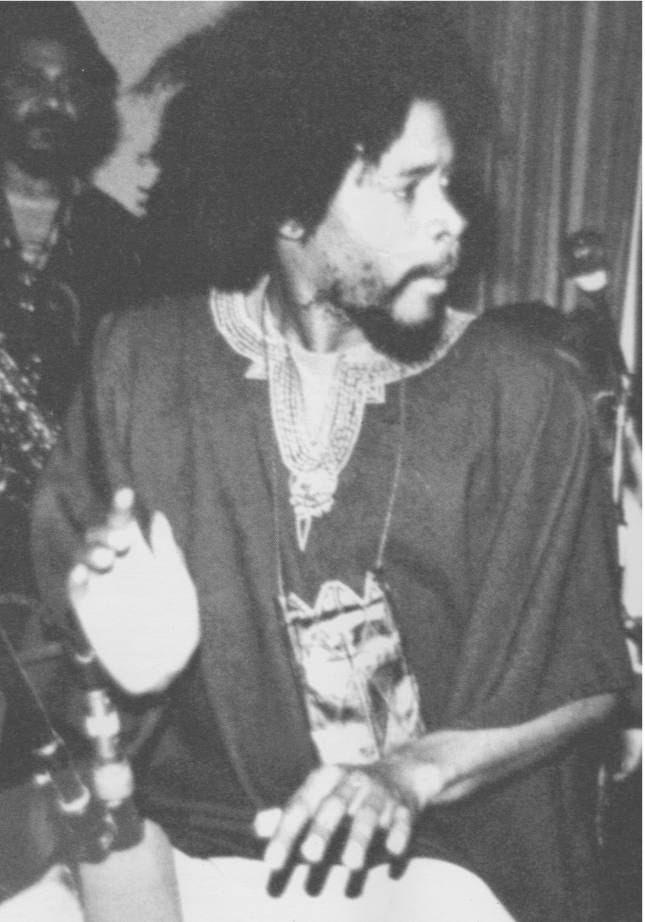

Interview with Mabrak

So instead, my mom sent me to keyboard classes, which is funny because this is how I really got into drums. One Friday night coming back from class, I heard the creative group two doors down, they had a rehearsal studio and they were playing congas at the time. I was fascinated.

And then the great Barrington Barrett taught me some stylings on the butter pan drum, little things I needed. The basic thing was to hold that fonde with the heartbeat sound in it. Once you can master that timing pattern, only then can you move on. So I just kept playing, playing, playing …

And it carne in handy in 1963. My primary school teacher, the late Enid Chevannes, was also the script-writer for a weekly radio show called Life In Hopeful Village. She asked me to play a part in it, as an actor. I did it, but then they’d have little concerts between scenes, and that’s what I really was interested in. I could play, but I had no drum. So I said, Could you get me a waste-paper container? A plastic one? They found one, I played, and then they were, like, Oh he’s good, let him continue play it. So they never bought me a drum, and that went on for fourteen years!

In the meantime, I was still living two doors down from Tommy McCook. He was away in Nassau in 1960-61 but had just come back to Jamaica to form The Skatalites. And he had a drum over there, so he’d let me practise on it.

In about 1969, I still didn’t own a drum but I borrowed one, just to appear

in my school play. I won an award, which led me to win the competition for National Junior Drumming Champion, in July 1970. It’s a drumming contest they used to hold every year. Tue senior section was won by Count Ossie, from what I remember. Right after I won that, I got admitted at Howard University in Washington DC …

One day I got this letter. The university found on my files that I was a drumming champion, so I got this invitation to go drum at the fine arts building.

I went, and loved it; they had real drums, too, from West Africa. This instructor, his name was Kojo Fosu, told me I had a different style of drumming.

Anyway, they had a tryout to lead the top drum and dance group at Howard – Contact Africa – and they made me the lead drummer for it, based on my ability to concentrate all the six or seven drums, and to correct anyone that’s off, on stage. From there, Kojo decided to move me up to the talking drum level. At the time, I only had seen it in magazines. He started showing me, and taught me the history of it. Talking Drum is the highest level of drum music. It was used in West Africa to send messages from hilltop to hilltop.

I had a few other musical experiences in the US. One summer I played with an R&B group in Harlem called Tue New Chapter, they were involved in a city programme called Summer In Tue Park. I only stayed two and half years at Howard, though, because my father died, so I had to go home.

But going back home in 1973, I knew I was now ready to record. That’s when I bumped into an old childhood friend, Bim Sherman. He knew I was a musician, and he was going to King Tubby’s studio that day. I tagged along. I recorded rasta repeater drum overdubs on his first hit, 100 Years.

This allowed me to re-connect with Tubby. He knew about my junior champion title and hadn’t heard from me in two, three years. So the session went pretty well, to the point that Bim suggested that I should do my own version of his instrumental. .. which I did, and put it out on my label, Lightning & Thunder. In exchange I was sort of channelling Bim, advising him.

In 1974, I performed in the National Drum Championship, at senior level this time. We played against Light Of Saba in the finals – Cedric Brooks, his drummers played against myself and the drummers of Mabrak. Actually, our group was initially called Genesis, it was a 7-piece drum group, but I changed the name to Mabrak, which means Thunder in Amharic. We knew that we were coming with a heavy sound so that is why I chose that word and that is why I named my label Lightning & Thunder, Issat Mabrak.

Anyway, 100 Years was my first record.

Liquid Talk carne about a bit differently. Hanging out at Tubby’s, he had that riddim I loved, Harry J’s persona! versi on of Liquidator. I decided to put talking drum on that from start to finish – which really fascinated King Tubby. He thought I was doing some kind of research project, he couldn’t believe I really wanted to put it out. He was blown away, and wanted a copy for his sound system.

My Drum Talk 45 was selected as the theme song for the 1975 Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference, held at the Pegasus Hotel in Kingston. This particular link carne from a friend of Tommy McCook. She was at his piace and his son was playing the record. She knew of somebody at the cultura! division of the government who was looking for a track that was Jamaican, but that the African delegates could relate to. This was the perfect match, and they loved it! To the point that a professor from Ghana even reviewed the album.

Tue Drum Talk album was an extension of Liquid Talk. After the first single was successful, I played it at Harry J’s, and they said they wanted to do a full album of their riddims. So the Harry J people wanted me and my brother Bush Mabrak to select nine more riddims from their library and make a compilation called Drum Talk. Just any riddim that we liked. That’s how the album carne about.

What helped too is that at the time, we were occasionally playing at Harry J’s, on sessions. I would just get a phone call. Hey, Leroy, what are you up to tonight? I was working by day at the Institute of Jamaica, in the zoology lab or in the natural history section, we were preserving the butterflies and insects from the collection. Tue sessions were always 10pm till 2am, which worked okay for me.

Leroy ‘Mabrak’ Mattis, interviewed by Seb Carayol in Aprii 2006.

[:]