[:en]Extracted from Honest Iohn interviewed with Robert Fearon aka Ribs from UNITY SOUND SYSTEM on 20 feb 2002

1: for the people who don’t know you, can you tell us how you become involved with sound system…

2: when was the first time you saw a sound system, info and memories…

I was born in Jamaica in 1953. I came to England when I was nine, my par-ents sent for me. In Turner Street, Kingston, where I lived there was a dancehall on the next side of the road, I Lived on this side in one of them little shanty shacks, you know. I will always have this memory of this dancehall, when I came to England it was always there. They had different sounds playing there. In those days the two main sound systems were Duke Reid and Coxsone. I heard Coxsone play. couldn’t go in the dance-. hall, but you could stand up outside in the street and hear exactly what’s going on, and feel the vibes and the atmosphere. Dancehall in Jamaica is not an enclosed thing, it’s more like a yard with an open gate, no roof. I was living with my grandparents because my parents come to England three years before me and my brother came. They came in a boat, like the Windrush. They were living in Kentish Town. My memory of my schooling is not.. even though Jamaicans speak broken English they could not understand a word I was saying. That’s the only memory I have of schooldays, struggling to get through it because no one understood what I was saying. And I had this Jamaican mentality, dance-hall and this and that – try relating that to the school teachers in the sixties, it wasn’t happening. I spent five years in school. When I was-fourteen they told me I was wasting my time. Mind you, I didn’t care, right, because music was it, sound system was it for me. I already knew. My parents, they didn’t want me to do any of that, because they thought sound system wasn’t really anything to do, as an occupation, whatever, but that didn’t gr] BB matter to me in any case, that’s what | was going to do. My dad was working on British Rail, my mum was a nurse,they Looked towards those things. So I wasn’t like outcast, but – He’s going to be soundman, no good, can’t understand him, bad boy.

3: can you tell us about your beginnings in the reggae-dub, how you did you begin and when, info, memories…

I did actually do a ‘proper job’ for about five years, till I was nineteen upholstery, and I worked in a factory packing coats, but I couldn’t hack it. I had to work because my parents weren’t going to let me just play sound system, they refused point blank to let me do that. I was buying records from Rita, she was in Finsbury Park, she sold Blue Beat, she specialised in it. It was very difficult to get records from Jamaica. You had to send your money to Randy’s, you’d get maybe twenty records for £10 and out of that as a selector for the sound you’d have to choose which ones you think is good enough for the audience, you know, because they’re not going to send you twenty BAD songs, they’ll send you some good, some bad, some left over from what they can’t sell, and whatever. I just decided that was what | was going to do, selecting, just like my brother decided he was just going to deejay. We just did it because we just love sound system, that was part of us, so we just decided that’s what weare going to do. In those days, to be a soundman, you did everything. You lift box, you run the wires, you string the sound up, and you actually play it. But you come up in the ranks. You join somebody else’s sound as a box boy. The first club I did was the Seventy-Seven, with Sir Fanso the Tropical Downbeat. He was the leading sound at that time in the North London. I heard his sound in the Seventy-Seven, in Holloway Road, and I Like the way it sounded. Me and my brother was there, so we hung about until the dance finished and we actually hitch a ride in the back of his van, and ask him if we could be around his sound, you know, and he said that was okay. This was the rocksteady era – Studio One, Alton Ellis, Delroy Wilson, Treasure Isle – and I was fourteen. Like I said, in those days you had to come up through the ranks, so you start from being a box boy, and then after maybe a year or so you progress to actually – this is going to sound silly – putting the record in the bag. After he plays it, he gives the record to you, and you put the record in the bag. Honest to God, that’s the wayit went. Then you spent about another year turning the volume control up on the pre-amp. Till you progress to the stage where you can actually play the ‘thing, and then if you’re good enough the chap that owned the sound would leave you now to do all of this by yourself. So I was like coming up through the stages, the hard way, believe me. In Fanso days and early Fatman days it was Afros – enough hair – and flares, we call them big belly trousers. We had tailors, if you knew a man who was a tailor – made to measure. Because I’m going to be Lifting boxes I’m not going to be that dressed up and I’m not going to be as smart, but it didn’t really matter because I was part of the sound. Sir Fanso left to Jamaica and took his sound equipment with him. Fatman used to deejay for this sound, so when this guy left Fatman decided he was going to build a sound, because there was a gap in the area, and Like I said | was selecting for this man before, so I would be the selector for the sound that Fatman built. And Fatman was the deejay for maybe the first year of his sound, and then my brother Roy Ranking came in and took over the mic. from then, you know. Fatman was a big London sound of the seventies – North London anyway, because each area has their sound. Even though he’s from Brixton, Coxsone was popular all over. Fatman was popular in North London, we never did go to Brixton to play. Duke Reid is another big sound, they would play everywhere. I played against them all, yeah man, wicked sounds, Neville, Shelley. Friends, yes… we are friends, we are friends… When you are playing against each other you are not friends,it’s strictly business and you don’t really care, you don’t want to lose. Fatman played dub, we played 45, we played vocals, we played drum and bass, we played everything. Certain tunes Like the Wailing Souls’ Very Well, we were the first sound in England to play these tracks. There’s quite a few of them – Ernest Wilson, I Know Myself. There were some tunes from Michael Prophet, which was Yabby You collection. Fatman Sound big, y’know, it was wicked, y’know. Fatman was the man who made these connections with Channel One and everybody, I was too busy playing the sound, he was the one went to Jamaica. | had locks at the time too, because at the time if you was reggae you had to have Locks, and so you didn’t want to be known as a baldhead, it was Like a crime. When I was playing Fatman Sound, we had a clash with Shaka and Coxsone. Now, Fatman had this tune with Shaka’s name in it, right, called Horseface Shaka. It was done by Trinity. We had the tune for about two years. We clashed with Shaka several times, I didn’t play the record. Anyway, this occasion Fatman decided I better Play this record or else I’ll be out of a job. The man is right. It’s his sound, he got the record made. I wouldn’t play it because of what it said on the record. I thought it was a bit too much. Horseface Shaka, it said, you’ve got a face like a horse, you should be in the market selling tripe. It wasn’t nice. This night, played the record, place tear down. | had to play it about four times, the crowd just reacted, went crazy. The end of the dance, Shaka says he will never, ever, ever playwith me again, and he didn’t. It was too much. We never played again. He never played in the Unity days. Put it this way, it became like a him and me thing. | did that with Fatman Sound, but even when | became Unity Sound he just didn’t want to know. That’s a bit sad though, because if you play with somebody and you lose, you go back again. And if you Lose again, you go back again. You keep going back until you win. That is like-one of the rules. He didn’t want to know. Well I had this tune in any case, so I don’t blame him.

4: can you tell us about your sound and productions in the reggae-dub, how you did you begin and when, info, memories…

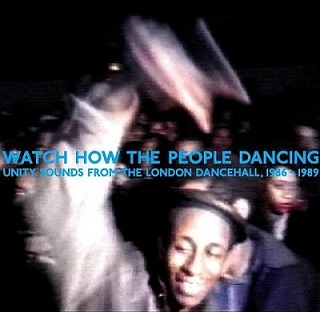

Sir Dee was my ex-wife’s uncle. He had a sound in Tottenham. His soundhad done what it had to do in the area and was now parked. I had played Fatman for ten years and couldn’t do nothing more with that. Now I wanted my own sound, didn’t have no money to go out there and buy ba equipment from scratch. My uncle in-law had equipment, even though they were a bit dated, but they can still work. He had a 600-watt transis- torised amplifier. Fatman used valves, he had the original hand-built sound, but in the eighties now we started using the transistorised amps more and more. It was a lighter thing to carry. So I built some new boxes, transferred the speakers from the old boxes into the new boxes. With the carpentry skills Fatman showed me I could build sound system boxes. I came up with the name Unity. That’s how Unity was born. July, 1982. We started in blues dances. Charjan’s house was the first house we actually played in. In Tottenham, Cornwall Road. When I was in Fatman Sound, Charjan was part of Sir Dee’s sound. So when the Unity sound was built he came with me, and my brother as well. The original crew was me, Charjan, my brother, and Dees, he drove the van. He kept the equipment in the van, he had one of those box transit vans, parked up outside his house. At that stage most sound systems kept their equipment in their vans. You couldn’t keep it in your house because it’s so big now. We were playing form 10 o’clock till 8 or 9 o’clock the next morning. We would start with up to date tunes, then from about five or six o’clock in the morning, Studio One was the right set of tunes to be playing, and Treasure Isle, everybody’s tired, grooving down. Peckings was the spot – anything you wanted from Studio One you could go to Peckings and get that. The soul records was introduced to the sound when it first came out, because we were playing in house parties, from 82-84. By 85 come we were a dub sound, we’re only playing specials, that is music about the sound sung by the artists in Jamaica, and exclusive dub-plates, nothing more. We wasnt playing no music that come out on the streets on singles or anything now. We got too big to be playing parties, our equipment was just too big to be moving to little houses,so we movedto clubs and dancehall as we called them. We played Four Aces for quite a few years, and you had to be bad. Only the best of the best sounds played in Four Aces. We had ten fights in the first ten weeks we were in there. Mind you, we were putting too much people in there at that time. People was like stepping on each oth- ers’ toe and so forth, which in our society causes violence. You mash a man’s toe, that’s violence. Whole heap of fights was going on in there. The violence is like part of thculture too. In them days you didn’t go to the dance unless you were a rude boy. You don’t go, you stay at home with your mum. But the best sounds passed through Four Aces. Our time in Four Aces was about three to four years, the last year we played with other sounds. For the first three years of Unity Sound we played on our own. It wasn’t until we got | that bad, that we started playing with other sounds, dub-plates and spe- cials, because then it’s basically competition. One has to play better than the other. The style had changed again. The hats were Kangol. The style of clothing was like whatever Jamaica was wearing at that time, and America. The rude boy kind of style. No more tailor-made now. Baggy trousers. The Locks was out. In the eighties there was this style now with about a milLion Lines, very short. This was before I even heard the word hip-hop. I was only hearing reggae then, nothing more. There was a dance called the water- pumping .. whatever the dance was, that was part of the fashion, to learn it because it’s actually supposed to be going with the music. But every- thing came from Jamaica, the dance they are doing. in Jamaica, because they invent the dance, they invent the name of the dance. So if Jamaicancome to England we’d see them do it, so we would follow that.

5: musically ….what were your influences when you were young and what you like/liked most…

We never thought of it as a London thing, it was just like a Jamaica tingwhat were doing. When | played Fatman we run a series of dub-plates Dennis Bovell done when he was with Matumbi, Guide Us Jah and a few more tunes like that. He was a brilliant musician, and he was selecting for Sufferers Sound at that time as well. We went to a recording studio in the West End where he was working at that time, and he mixed us some stuff. This was Fatman connection. But with Unity now it was a different thing. directly Jamaican, the Jammys connection, the Striker Lee connection. Me and Jammys were linked from Fatman days. Fatman met him when he was working in Tubby’s studio, cutting the dub-plates and mixing the tracks. When Jammys came to England, Fatman needed somewhere for him to stay so he stayed in my house, hence us becoming friends, and even greater friends than him and Fatman was. When | built Unity sound there was two persons that said Yes, go and do your own thing. Jammys was one, and Bunny Lee was the other one. What that meant to me was that, from | built my own sound, I didn’t have to worry about exclusive music, because I’ve got two of Jamaica’s main producers now encouraging me to do this, you understand me. I didn’t have to send to Jamaica no more for anything. lt was like a phone call – Jammys, I’m playing against somebody, or whatever, and he will send me a fresh selection of tunes on dubplate. He benefitted from it too, because anything that | played from his production that the crowd took, | would ring him and say; Well, Jammys, that ela ee tune….so he knew which one of his tunes was popular. It was a good relationship. If there was a track that | really Liked, | would ask him, Can | havethis, and from it wasn’t interfering with Greensleeves, he would say yes. ! gave him a few tracks, | don’t even know what he done with them. Sweet Reggae Music, Nitty Gritty, | asked him for it, because we was playing it quite a lot on the sound. Few other tunes as well, The Exit by Dennis Brown, quite a few of them, Bandalero, Pinchers, he gave me those ba to release over here.

6: what can you tell us about the story of sound system in Uk/London/Jamaica……difference with Uk/Jamaica/London….who you knew, worked, had collaborations in London/Jamaica sounds systems and studios… who you liked more in London/Jamaica at those times….

At that time there was Taurus, Saxon, Java .. But Unity had a vibes, we had a vibes. We could play anything and the crowd would go mad. Mind you, we had a set of crazy people in the sound, which would trigger off the crowd. We just had this vibes where we played which was Like no other» sound. No other sound of that era had the vibes that we had. If you want to be a soundman that just stands there and puts on a record, that is alright, but if you want to be a bit more, then you have to do a little bit more around the sound, whether it’s jumping up in the air and waving your arms around. Now round the sound we had one crazy set of man. To dance around the sound, we needed space, you needed space. Nobody stood still, everybody was on the move constantly, making noise, shouting pull up that, and more time, just pure that, under the good influence of the good marijuana. The starting pistol, we brought that in, it could make a lotof noise, and smoke. Ruddy Ranks, he was the one, he was Like our cheerleader. Pick the right tune and then let this off, and the crowd would go mad. Like Hill and Gully by Johnny Osbourne, that was one of the big tunes on the sound. We was the only sound that played it on dub, before: it was actually released, and it was very, very popular. Whenever we played that it would just mash down the place, and he would Let off three or four shots. It reached a stage where anything we played, the crowd would just go mad. We started with four people, we progressed from there. Charjan brought in his brother called Jack Reuben, he was deejaying, because deejays was an essential part of the sound system now. You played the vocal, you then turn it over, you played the version, and you give it to the deejays, who’d talk on it, whatever lyrics they would formulate in their head. The more deejays you have on your sound, and the better they are, is more popular your sound is. Jack Reuben, Yabby You, Charjan, Roy Ranking, Demon Rocker, Raymond Napthali, Flinty Badman, Speccy Navigator, The Riddler, there was a few more. At that time whosoever was a deejay in Jamaica, Admiral Bailey, Chakademus, Peter Metro, Josey Wales, Lieutenant Stitchie, they all had to pass through, come to the dance where we were, and then for maybe half an hour they would be on the mic, that is part of it as well…..They would know our connection with Jammys and so for them to be coming to our dance, itwas just a natural thing. Little John, Sugar Minott – he was living n the area where we were,when he created his Black Roots Label. Speccy Navigator brought Selah Collins in. He came along one night gave him the mic, sounded good. Always the sound first, with every one of them. Ruddy knew Mikey Murka, brought him in, | heard him sing on the sound. Kenny Knots was going out with one of Ruddy’s family, used to come and sing on the sound. Peter Bouncer and Jack Wilson lived in the area. I think Jack Wilson used to be part of a band called Black Slate, vocalist for them. Jack Reuben brought in Demon, and Demon brought his brother Flinty. Everybody normally brings someone, you walk in crews. They all have to pass through the sound. The sound was was our church. That was our life. We lived that sound. Weekends we played out. During the week I rented two rooms above Regal record-shop, where we would meet and discuss whatever we were doing inside the sound, and we used to meet there every day. So it was like a seven days a week thing, we was always together: there were certain things we would fight against. We would fight against cocaine, we would fight against slackness, them two main topics, we would fight against batty man we call it. This was just our mentality, you know, feel no way. But ganja now, plenty of ganja, plenty of that. They wouldn’t smoke crack because it smelt, and we used to fight against that. The music was fighting against it too. You’d get singled out in the dance and Look Like a fool, you could even get thrown out. So it didn’t happen, it did just not happen. Ganja was the thing. Herbman is there hustling.

7: you have been involved in the reggae scene since a long time , can you tell us something about Reggae in that period…..

I’ve spent too many hours standing behind a turntable, believe me. Hour after hour, weekend after weekend. In Unity crew I never saw a Saturday night in ten years, for ten years I didn’t see a Sunday afternoon, or maybe I’m getting in from a dance about this time, I’ve dropped off everybody else. After a while it took its toll. Anyway, I can’t bleach like that no more, no way. I’ve got two hernia operations from Lifting sound system boxes, one with Fatman and one with Unity Sound. At the end of the eighties now the ragga music came in, the deejay music, did an immense amount of damage to reggae as a whole really. It was too much, and they weren’t saying a Lot. I mean, reggae music, we Look towards the music for guidance. A lot of us knew where we came from through the music. Burning Spear, he’s the one that let me know about Marcus Garvey. It was more than just music, we lived it. When Yellowman came we looked upon him as a joke deejay, he made you laugh. We respected him because he was supposed to be comical. When Shabba Ranks came along, iad ay 4 X-rated, it was like, no, and because it sold everybody in Jamaica jumped on it. The new wave of sound, Nasty Love, Gemi Magic came in with that deejay stuff. Different thing now. Now you have one guy, and he’s got two or three or maybe more versions, and he would be mixing from one tune to the other. Our days, it was one turntable, one selector, another guy that tunes the amplifier, several deejays … I grew up Listening to Delroy Wilson, Alton Ellis, Slim Smith. What am I going to start listening to now? Shabba Ranks? It can’t work. The music caused me to stop selecting, because couldn’t stand up and play these records, there was no heart. It reached a stage where the dancehall now meant that instead of you playing one record once for the night, you’re playing the top ten over and over and over again. Everybody’s playing the same thing. I’m coming from where everybody’s playing something different, that was the art. To me, you have certain tunes you play at the start, certain tunes you play when the dance is kicking, and certain tunes you play when the dance is tailing off. You reach a stage now, bashment, reggae or whatever, twenty million Bounty Killer, twenty thousand Capleton, some Sizzla, and everything finished. So I eased off, my brother played the sound for a Little while, I didn’t even go to Demon Rocker and Flinty, they went off to be the Ragga Twins. Speccy the Navigator went into the rave scene, travelling all over the world, he’s still doing it now. Peter Bouncer worked with Rebel MC. They all worked for one person at some stage, Shut Up And Dance I think they called themselves. I thought these guys made it their duty to come to our dances, taking whosoever was on the sound and going off to record them on something else.[:]