https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twinkle_Brothers

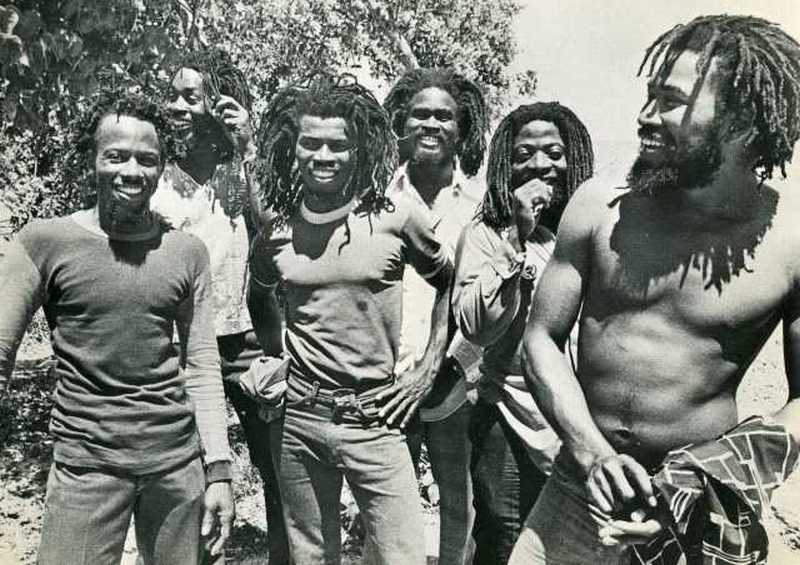

The Twinkle Brothers are a Jamaican reggae band formed in 1962 by brothers Norman (vocals, drums) and Ralston Grant (vocals, rhythm guitar) from Falmouth, Jamaica.The band was expanded with the addition of Eric Barnard (piano), Karl Hyatt (vocals, percussion), and Albert Green (congas, percussion).

After winning local talent competitions, they recorded their first single, “Somebody Please Help Me,” in 1966 for producer Leslie Kong. This was followed by sessions for other top Jamaican producers such as Duke Reid, Lee “Scratch” Perry, Sid Bucknor, Phil Pratt, and Bunny Lee.

The band worked in the late 1960s and early 1970s on the island’s hotel circuit, playing a mixture of calypso, soul, pop, and soft reggae, and in the early 1970s, they began producing their own recordings.

Their debut album, Rasta Pon Top, was released in 1975, featuring strongly-Rastafari-oriented songs such as “Give Rasta Praise” and “Beat Them Jah Jah”.

As well as producing Twinkle Brothers work, Norman Grant also produced other artists since the mid-1970s, including several albums by E.T. Webster.

In 1977, the band were signed to Virgin Records‘ Frontline label, leading to the release of the Love, Praise Jah, and Countrymen albums.

When the band were dropped by Virgin Records in the early 1980s, Norman Grant moved to the United Kingdom, and carried on effectively as a solo artist, but still using the Twinkle Brothers name, and continued with regular releases well into the 2000s, mainly on his own Twinkle label.

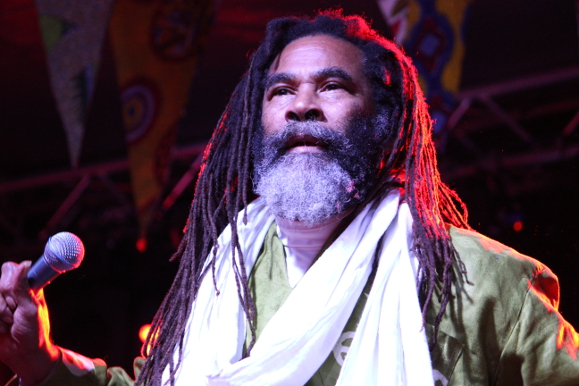

Currently led by founding member Norman Grant – as well as legendary bass player Dub Judah, Black Steel & Jerry Lions on guitar, Aron Shamash on the keyboards, Barry Prince on drums, and their engineer Derek “Demondo” Fevrier – the Twinkle Brothers are widely considered to be one of the best live foundation reggae bands in circulation, and they continue to play regularly all over the world to a loyal fanbase.

Interview: Norman Grant from Twinkle Brothers

Friday, January 15, 2016

https://unitedreggae.com/articles/n2034/011516/interview-norman-grant-from-twinkle-brothers

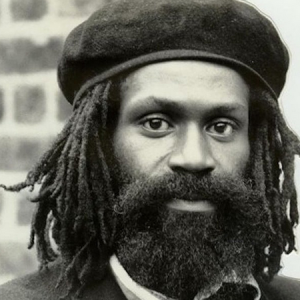

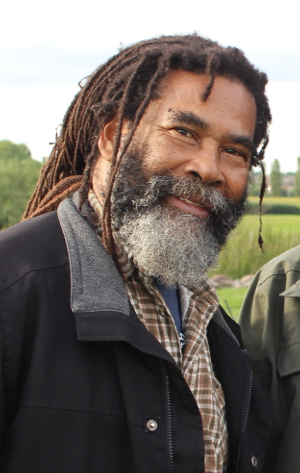

Let’s do this” says Norman Grant, lead singer and more visible half of Jamaican duo Twinkle Brothers, striding towards his interview, seconds after stepping off the stage. Burly and grey around the beard, he still has a youthful look about his face – especially when he smiles.

Norman and Ralston hail from in Falmouth in the parish of Trelawny on Jamaica’s north coast.

It’s a well-documented story* that he and his sibling made instruments out of fishing line and cans that they found on the beach. “Oh yeah” he recalls “Because in those days we couldn’t afford to buy them. It was mainly drums and guitars you could strum. When we started doing things like that I was like five or six, around that age.”

It’s also documented that a few years later the child duo were named Twinkle Brothers by a Rastaman called “So Mi Say” because they sang under the stars. Less is known about So Mi Say – a mentor to these children long before the adolescent Rasta rebellion that would eventually inform their song Since I Throw The Comb Away.

We started when I was like five or six, around that age

“He was one of those early Rastaman that we used to listen to in the 60s” says Norman “We’d sit around and he would be giving us lectures, telling us about Rastafari, self-reliance, eating Ital food because he’d tell us about diabetes and these things that salt and sugar cause. So from those times there was somebody who was telling us what to do.”

Further instruction came from the radio. “By the age of ten or so we were more or less listening in America you know? The American or the English songs. We started out singing songs like Tell Me My Darling If You Love Me – those kinds of melodies. In those days we were singing soul music and different kinds of music.”

Local recorded styles were not played on the airwaves but began to get recognition via live “Festival Contests”. “In those days it was called ‘Pop and Mento’. Because Jamaican popular music at the time was called mento… and pop – we would adapt the foreign thing.”

A drummer as well as a vocalist, Norman has an interesting insight into the way music was made in Jamaica back then: that singers were as important as musicians in establishing soon-to-be dominant patterns like ska or rocksteady. “Because in those days the band would play to how the singer could sing, so before they would give songs titles like ska or rocksteady or reggae there were certain songs they were making with certain feels. Because the singer can only express themselves to how the beat was going. Now, the ska beat, you could quick up a song but still there were songs where you would have to do it rocksteady style to express as an artist.”

In those days the band would play to how the singer could sing.

When the teenage Norman recorded his first tune in 1966, Somebody Please Tell Me, the tempo was changing from ska to rocksteady. He’d been singing since the age of six, in church and in parish festival contests – winning medal after medal – so going to producer Leslie Kong’s Beverley’s label to record was not as intimidating as you’d think.

“From ten years old we used to go to Kingston on school holidays, link up with the producers and we would always get picked because we were entering the festivals. We were always doing well. So we’d go to auditions and we’d get picked for Beverley’s, for Duke Reid.”

Matthew Mark, Norman’s inaugural song with his brother, plus two friends, was cut for the infamous ex law enforcer Duke in his Treasure Isle studio. It was something of a backward step in terms of financial compensation compared to the Chinaman at Beverley’s. “Well at least I got £10 for the Beverley’s song! With Duke Reid we got six records! We got six copies of the Duke Reid song.”

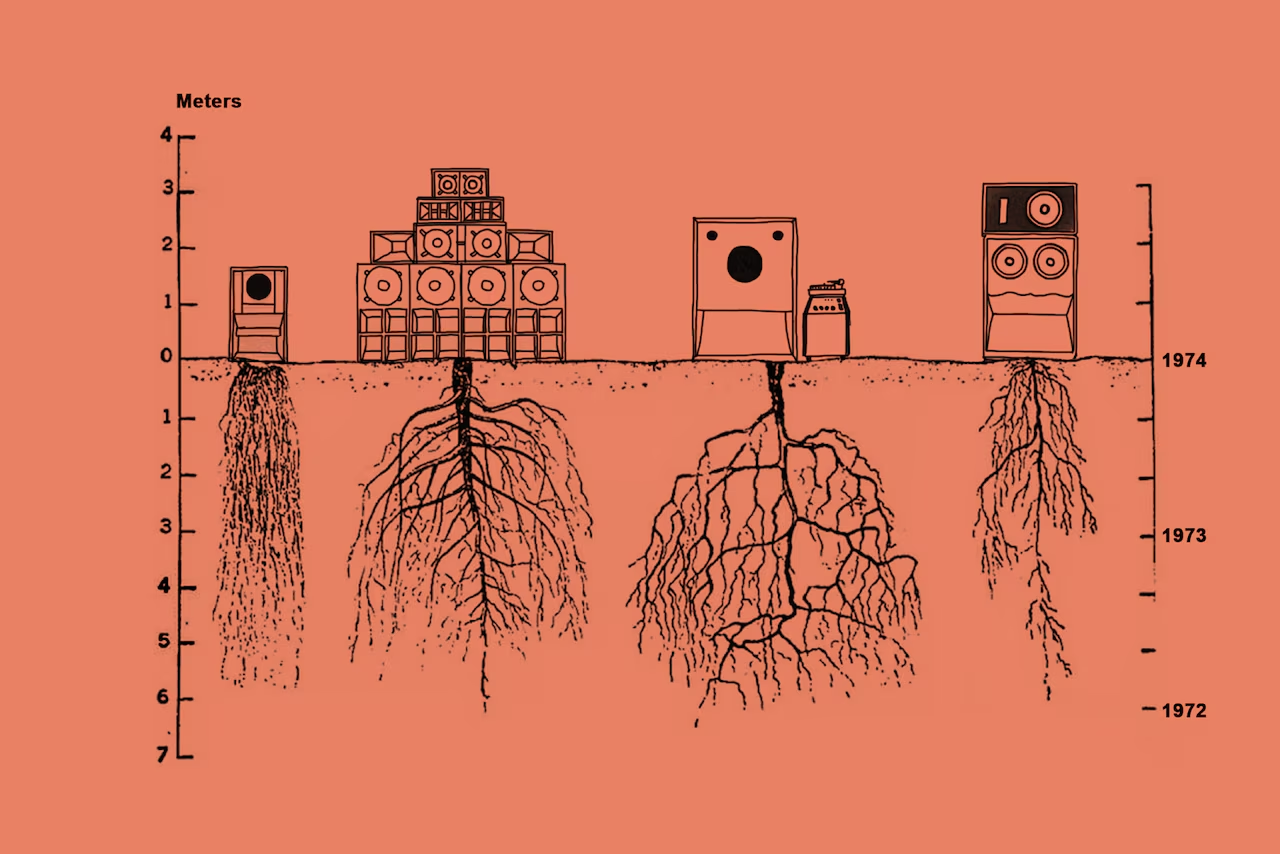

“But that was all good still,” he continues “Because in those days we weren’t even thinking about pay. We wanted to do the music. Because music was still expensive to produce. Even at Duke Reid or Coxsone they had their sound systems so they were making the music to play on their sound systems. It wasn’t like lots of songs were getting released. You had to go to the dance to hear the songs play. So there were a lot of songs that were very, very popular but there were only a few people that had record players. Sales for each Jamaican artist was when you got known abroad – then you would start to eat some food as we would say! So it was all good because luckily we started to produce for ourselves early in the business so that made a difference.”

We started to produce for ourselves early in the business

In 1970, when the reggae beat was in ascendancy, the now grown Twinkle Brothers sang on the first ever session using the soon to be hot Soul Syndicate band for producer Bunny Lee. “What happened was in Jamaica you have certain musicians that would be carrying the swing within the studio musicians. In the first half it was like Familyman and Carlie – before they started working with Bob straight they used to record most of the songs in the late 60s and early 70s. Then you had Skin Flesh and Bones which was Sly and Lloyd Parks then it changed [to Soul Syndicate]”.

By the mid-70s Twinkle Brothers stopped playing with other bands and crystallised around a core line-up of Norman (drums and vocals), Ralston (vocals and guitar), Derrick Brown (bass), Eric Bernard (keys), Karl Hyatt and Bongo Asher (percussion).

They began fashioning the initial material bearing the eschatological deep roots Twinkle sound we know today.

In 1975, these were remixed and consolidated into debut self-produced long player Rasta Pon Top, mainly built at Channel One studio.

Typical of their newfound path was the title track, a pulverising ancestral recollection of colonial slavery and the reckoning due under the guidance of Rastafari. “We actually did two versions,” Norman reminisces “One version at Channel One and another version we did at Harry J’s studio when we were making the Countrymen album.” Norman says he did most of the brothers’ writing during their 70 album career – Ralston would contribute maybe “One or two on a few albums. He’s starting to make more music now – now that he has his own studio.”

At the same time Norman had started visiting England and after releasing LPs there via Grounation and Carib Gems, the group signed to Richard Branson’s Virgin Frontline records. “Yeah that was late 70s – for five years and they got three good albums out of us.” The first release was the 1978’s Love, a combination of the hard stepping drums of the islands new ascendant kit-man Sly Dunbar with a nod to the romantic songs that commenced Norman’s occupation (such as the haunting I Love You So recorded at Treasure Isle and mixed by future Tuff Gong engineer Errol Brown).

Although reggae nowadays is conjoined to the prerecord and recycle rhythm culture Bunny Lee originated, Norman relishes those sessions for the way the musicians would work to what he wanted. “As I was saying, those guys had to play to how we were singing. It’s not like we were singing to match the rhythm. Because the music has changed now. Musicians make a rhythm and the singer sings to go with the rhythm. In those days we would sing a melody and then the musicians had to play to fit. So when those guys played with us it was an experience for them also as musicians because we were in a different bag with our music. Those guys were more than willing to play for Twinkle plus they were getting paid.”

Music has changed now.

Musicians make a rhythm and the singer sings to go with the rhythm

The three album run at Virgin ended on 1980’s Countrymen. It contained some of their greatest compositions including Since I Throw The Comb Away and Never Get Burn – yet these lacked the propulsion of their single incarnations.

In past interviews Norman has been critical of how Virgin messed with the earlier Jamaican mixes. Today he is more philosophical. “We mixed it in Jamaica and gave them a finished mix and they wanted us to do it bigger because we did it on eight track and then transferred it to 24. So in England they wanted to put a different vibes within the mix which was good because it was a crossover thing. I have nothing bad to say about it because the other mix is still out there and there are more mixes I haven’t released yet.”

That same year Norman toured and sang with old friends Inner Circle (who he had known since their early days session-ing for Bunny Lee) after singer Jacob Miller was killed in a car crash.

Did he ever think that was going to be a permanent thing? “No. I was coming to England maybe six months after that so for me I just went on the road to North America to see what was happening. Because we’d been working with them from in the 60s. They are the same guys who were in Third World – it was the same band.”

Once settled in his newfound home in England, Twinkle Brothers cemented an association that would carry them to the ears – and chests! – of the next generation of roots devotees, recording for mythical soundman Jah Shaka.

During a recent concert at Reggae Geel festival in Belgium the Twinkle band – which today includes UK luminaries such as Black Steel on guitar and Dub Judah on bass – paid tribute to Shaka, covering his Revelation 18. In some ways the Twinkle ethos can be seen as a precursor of the Shaka sound that evolved into what termed “UK Dub”.

Shaka was always playing Twinkle music from the 70s

“Well, Shaka was always playing Twinkle music from the 70s. I started coming to England in 1975 so Shaka would seek us out with anybody coming from yard. Plus when you would sign up with a record company they would give the sound systems the tape to cut dubs to play in the dancehall to see what the people love. So he was one of the kind of producer-promoter- disc jockey who would play Twinkle whether Twinkle was in the dance or not. Our music is in his vein – in his type of melody that he’d play.”

In 1986 the group galvanised the reggae scene in Poland by touring there – and initiated another long standing collaboration with Polish artists Trebunie Tutki. Linking Shaka and Trebunie were prescient moves anticipating the directions in which reggae would spread worldwide.

“When we went there, still the people knew the music so that’s a good thing with music. We only go where the music takes us. You go to countries where English is not their first language but they will sing along to most Twinkle Brothers songs. And they will even thank me for helping them to learn English by listening to the records so that’s good! For me, when I can go out and put the mic to the crowd and they can sing my melody that shows that people are listening. So for Poland and the rest of the world we just followed behind the music.”

We only go where the music takes us

Yet the years of entertaining foreign youth drawn in by the heavy bass-lines have not blunted Norman’s African consciousness.

At both Geel and One Love he rebuked his European admirers’ ancestors between songs for their colonial holocaust. Afterwards, perhaps mindful of the post-millennial tendency to see “anger about racism” as “racism” he does not press the point but widens it.

“You know, I do my little bit because what we are talking in the lyrics that we sing from that time till now haven’t changed. I remember we used to sing “Chant down the Berlin wall” and we saw it going down. We’d sing about how Mandela must be free. We’d see things happen. So it’s good that people are listening. It’s not like we’re singing on deaf ears because for myself it’s not like we’re promoting anything. Because the good word they will have to seek: “Seek and ye shall find””.

Twinkle have plenty more recordings to add to the already substantial pile – for their own Twinkle label and for other producers.

“I’m always working on stuff. I have more than 70 unreleased albums, so we make sure we pile them up! When I’m releasing we don’t even put out one – we put out three and six and eight or those kinds of amounts. But right now vinyl is still selling so what we have to do is repress our back catalogue because in the first place we can sell even more back catalogue than new stuff. Because when you release new things when it comes out it’s free. This generation they don’t buy music. They think it’s free. People buy a CD – they put it on their computer and file share it with each other. But it’s good for myself that people turn out to see our live thing so we give thanks.”