https://unitedreggae.com/articles/n420/071210/interview-prince-alla-part-1

By Angus Taylor on Monday, July 12, 2010

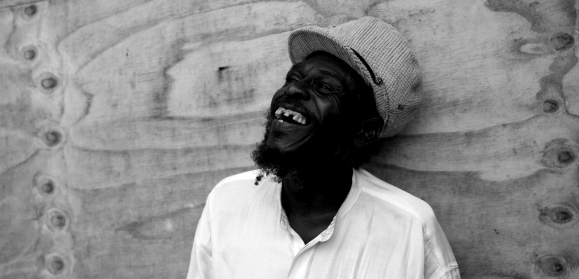

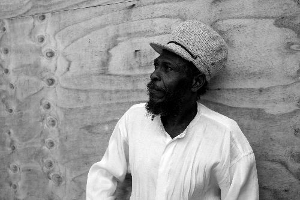

Dubbed “The Gentle Giant”, Prince Alla (born Keith Blake, St Elizabeth Jamaica) is one of roots reggae’s most irrepressible and warm-hearted characters. His demeanour is something of a contrast from the anguished dread-serious biblical tones of his records, which take Old Testament Stories and place them in the context of societal injustice in Jamaica and the world. His most famous records were cut in the mid seventies for Tappa Zukie’s Stars and Bertram Brown’s Freedom Sounds labels. Yet despite keeping busy in the last two decades recording for UK and European dub-reggae producers, where his strictly roots and culture approach is well suited, he still lives humbly in West Kingston as he has since his youthful days. Angus Taylor found the kindly veteran on fine form as he enthused about sports, music and spirituality in equal.

You are associated with the Greenwich Town/Farm area of West Kingston. Where were you born?

I was born in St Elizabeth but I came to Kingston when I was a little beenie baby. My people they were from the country but they just came into town to live with my grandmother and we just lived from that time until now. I was in Trench Town for a little time. I spent some time in Trench Town as a youth and then the rest of my time in Greenwich Town.

Which other singers did you grow up with?

My favourite one that I grew up with was Slim Smith. He had a girlfriend in Greenwich Town and he would come in the nights and we would go in our old car and he would sing for the whole time and I would be listening! I can’t remember the exact age but he was bigger than me. I was just a little youth at that time. He was a very nice person. Loving. Every time I heard him it was just music he’d talk about. I used to call him my Sam Cooke. My Nat King Cole.

I used to call Slim Smith my Sam Cooke. My Nat King Cole

You knew your future producer Bertram Brown as a child. What was he like?

Yes I grew up with him in Greenwich Town same way. Knew him from small and knew his whole family. He was irie but he had to work hard in a rum store, J Wray & Nephew. He was the accountant there as a little youth. Nice person. We used to go out to sea and catch fish and do all kinds of things. He was a man that could play football very well! He used to be on the outside left. Someone would pass the ball to him and I’d say, “Run! Gwaan B!” and he’d run in from the outside left and go BLOOOOMM! He was hard man because he had a good left foot. So every time we’d give him the ball he’d run in from the wing and send it in man!

How about your own football skills?

My own football skills weren’t so big. I used to love the cricket! (laughs) Now and then I’d play a little football but I used to love the cricket more. (laughs) Because in those times we didn’t have any pads or gear and you would get some licks! And sometimes you’d have to retire! (laughs)

You started singing in Methodist church I believe?

Yes because my grandmother used to go to a church that was right next door to me and she was part of the choir. So when they would have an Easter celebration or Christmas or any of those things then we would come and sing Our Father. I was so little then that I didn’t know all of the words! But I used to sing it and they’d say “Nice!” so I used to love it. She used to sing tenor and it used to blow my mind to hear the high tenor with the harmonies! That’s why I loved the harmony group singing too.

Were you religious as a youth?

I used to go to the church all the while because in those times you had to! Grandma was strict about “You have to go to church and Sunday school!” And because it was so near if I was late some teacher would descend and call over the fence and say, “Where’s where’s where’s where’s him???? Why he don’t reach yet????” (laughs) so I had to go you know!

How did you enter the music business?

I used to live with my father and when I started to Ras up my hair he said, “Bwoy watch yah now. If you gwaan Ras up your hair you cyaan stay here now”. So I said, “Alright” and I just went down to the Greenwich Farm fishing beach. I just started coming into the music because of the influence of Milton Henry who could play the guitar very nicely. I just said, “Yes!” and started rehearsing. I’d just left school then and I’d met Joe Gibbs. He used to have a girlfriend who lived down the bottom there and he used to come and hear me sing with Milton Henry and Soft Roy Palmer. He used to sing and he said he wanted to join the group but when he joined the group he couldn’t sing so we said, “better you be a producer now”. So he said, “Alright” and started producing and we did a song for him at Federal Recording Company.

I used to live with my father and when I started to Ras up my hair he said, “Bwoy watch yah now. If you gwaan Ras up your hair you cyaan stay here now”. So I said, “Alright” and I just went down to the Greenwich Farm fishing beach

That was the Leaders wasn’t it? Were they your first group?

Yes my brother! They were my very first group and my very first songs – everything.

The Leaders were often on flipsides of rocksteady records. Was this frustrating?

No because in those times when you were on the B side of some artist it was alright. Young ones wanted to be there. In those times people would big big you up when I said, “I end up on the flipside of here man!” In those times it wasn’t a problem. It was nice. It was like if you were on a football team and you’d have a big player and say, “Woy… I play wi dem you know?”

Did you do any voicing for Joe Gibbs after the Leaders?

Yes once I think I did a song for him in ’98 or ’97. I did a song over Nah Go Dem Funeral. I did it over for him. And in the 2000’s I did some songs for him before he died but I don’t know what happened to them.

When Joe Gibbs joined the group he couldn’t sing so we said, “better you be a producer now”

Why did the Leaders finish?

Milton Henry migrated and went to America. Me and Roy Palmer were still there but Milton was the inspiration for me. So I joined up with Roy Palmer and his little brother named Frankie – Frankie Jones – and we started recording for Tappa Zukie. He was always around in Greenwich Town even as a little youth. I was a bit bigger than him. He was a nice little youth back then.

But in the late sixties, before you started recording for Tappa you left West Kingston and went to the Prince Emmanuel Edwards “Bobo Dread” camp at Bull Bay.

Yes I left and went there for a few years and it was a little before I recorded for Tappa Zukie. That time was very nice at the camp man for the few years I was there. We just sang hymns and courses and we kept the Sabbath day holy and those things there.

Was bible reading a big part of your ritual?

Every day. Because I was a priest from the altar too. We had seven priests and I was one so I had to carry out services some times. So every day we had to read the bible whether you were carrying out the service or sitting down in the congregation.

Did this inspire your later songs for Tappa Zukie and Bertram Brown which draw on the stories of the Old Testament?

Yes. All of them. Man From Bosrah: because one day I read the bible and said, “Melchezidek met Father Abraham come from the slaughter with his garment dipped in blood”. In those times I didn’t even realize there was a place on earth named Bosrah. But I saw it in the bible and I liked that. His garment dipped in blood – blood red and I said, “Wha…” so the idea just came up and I sang off that. Melchezidek was the high priest. He had no mother, no father, no beginning of days nor ending of time. Same with all of them. Daniel In The Lions’ Den – Bible. No Go Them Funeral – Bible. That was reasoning about Jesus and his disciples and how one of them said, “I can’t follow you today because I have to go” and he said, “Leave that and come man”. But when you really realize that what he wanted was to stray and follow Babylon system – that is the real funeral. It’s not just a funeral for when somebody dies, because when somebody dies you have to bury them. The System is the real funeral. The System that tells you you have to die to go to heaven and those things. So I say, “I’m nah gonna follow dem system” so I say, “Nah go dem funeral”. That is what I really mean. Not if my mother or my brother or my good friend dies I don’t go. It’s Babylon System that I don’t follow. So I feel like it was just as Jesus was telling the disciples, “Come man, don’t follow them ways. Follow me and come” it is symbolic of a funeral. But I see it bigger than that. I see it as the System is a funeral! (laughs)

When somebody dies you have to bury them. The System is the real funeral

How come you left the camp in 1971?

Why I left was because there started to be a little division in the camp and I didn’t like division. Some man started calling themselves David House and This House and that so I just left. But the principle there was always right – it was just some of the people there would do some things. That was why I really left. Now at the Bobo camp we didn’t really play the reggae music so I left it out. But all the while Earl Chinna Smith used to look for me and say, “Bwoy, why don’t you come back into the music” and all this so I said, “Alright, alright, alright…”. So we did the first Freedom Sounds. We started off with Freedom Sounds and he did the first song with me. He said, “Come to Freedom Sounds” and carried me to the studio and we did a song there.

I loved this boxer by the name of Cassius Clay. When I was a youth that was my boxer man! Every time he boxed I’d always say, “Yes! Him gwaan beat everybody!” [Sonny] Liston, George Foreman, everybody! And you know in Jamaica they love to call you a nickname. Everybody has a nickname. If you’re fat they call you Fatman. If you’re slim they call you Slimma. So there was a brethren down the Farm who loved to give nicknames. He was the father for nicknames. So he said, “Yo! You feet a jump up! You name Prince Alla!” and everyone said, “YES MAN! YOU NAME PRINCE ALLA!!!!!”

Did you used to listen to Muhammad Ali’s fights on the radio?

In those times I used to listen to him often and go, “I am the greatest!” and “Booma yea! We are gonna kill Foreman in Africa!” and “Joe Frazier he is a gorilla!” (laughs) As a little youth I used to listen to a thing called Radio Fusion and hear them there. In those times I hadn’t seen a TV yet!

What was the atmosphere like in Jamaica when he won a big fight like Sonny Liston or George Foreman in Zaire?

It was a surprise because most people thought he couldn’t win. They said Liston was a prisoner and he was big and rough and tough and beat and killed everyone! But I said, “Cassius Clay ah my boxer man!” But the biggest surprise was when he beat George Foreman too! It was like fire man! People started coming on the streets with pots and pans knocking them, “BANG! BANG! BANG! BANG! BANG!!” and you heard over and over on the radio, “I am the greatest! I am the greatest!” People used to love calling that and they used it in songs too. Prince Buster and Dennis Alcapone too! “I am the greatest!” (laughs)

The biggest surprise was when Muhammad Ali beat George Foreman too! It was like fire man! People started coming on the streets with pots and pans knocking them, “BANG! BANG! BANG! BANG! BANG!!” and you heard over and over on the radio, “I am the greatest! I am the greatest!

So when you came back from the Bobo camp it was Freedom Sounds you worked with first before Tappa Zukie?

I think it was Freedom Sounds first. We did a tune together at Randy’s studio by the name of Judgement Time and another one Thank You Lord.

So after that you recorded Bosrah for Tappa Zukie at Lee Perry’s Black Ark studio.

Yes, because one day I was at my home and going round my house singing this song when Tappa Zukie passed. He called me out and said, “I hear it you know! Come!” and we went inside and he said, “Please Alla! Do that song for me!” So we went up to the Black Ark studio to see Lee Scratch Perry and when I went in he said, “What you name man?” and I said, “They call me Prince Alla” so he said, “Sing the tune!” So I started singing the tune and he said, “Wha…” and he held me and started spinning me round and going all (makes weird noise)! And I thought, “This is a genius man!” So he said, “Come!” and we went in the studio with Upsetters band. I think Melodians were doing some songs the same day too.

Did they help out with the tune?

Yes one of them did – Tony Brevett. Along with Soft – my original harmony man! Because Milton Henry was still in a foreign. He was gone a long time!

What were your memories of working with Scratch?

He was great. But sometimes he did things which you just looked upon and didn’t understand. He used to do some things and make some moves like he’d grab a bottle and quarter fill it with water and knock it, “ting! ting! ting!” And then he’d half fill it and go, “ting! ting! ting!” Then three quarters and, “ting! ting! ting!” Then full, and then he’d put all of those sounds on tape so when he was mixing the tune he’d use them. So you’d hear “”ting! ting! ting!” then “tong! tong! tong!” “tang! tang! tang!” (Imitates the sound changing pitch and being put through effects) All these things he’d so this man was great!

Lee Perry was great. But sometimes he did things which you just looked upon and didn’t understand

And obviously you worked with the other master engineer King Tubby on your tunes for Freedom Sounds.

King Tubbys was great too man. When I did the song for Bertram Brown I Man Saw Great Stone at Channel One, we took it to be voiced at King Tubbys. But King Tubby didn’t really record songs then. He used to use the other engineers. I think it was Scientist who took the voice. But then Tubby came round and said, “A who sing that tune there?” And because him and Bertram Brown were friends – because Bertram worked at Wray & Nephew and used to carry him liquor there and things like that – he said, “it’s my artist!” and Tubby said, “Wha…” So I said, “Bwoy, King Tubbys, I know you don’t really mix tune for other than yourself, but I ask you – mix it for me!” and he said, “Bwoy, I really like the tune. I’m gwaan do it”. He went round the corner and came back with a little box and I said, “I’d like you to make a sound like a stone you know?” and started to play sounds until it went “BRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRR!” (Imitates thunder) and I said, “Yes!” He said he had a sound off the news, because in Jamaica you had the BBC news, and the sound went “BEEEEP!”(Imitates Tubbys test-tone). So when the tune started you’d hear “BEEEEP!” from BBC news and then you’d hear “BRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRR!” the stone and then the organ would come in. King Tubby did that! He brought the stone and the beep man! He did everything for me special!

What were the distinctive styles of Tappa Zukie and Bertram Brown as producers?

With Tappa Zukie in the studio he loved horns in his tunes! He loved to arrange and tell you to do something along to the hornsman. But Bertram Brown was a man who would mostly just ‘low me up and say, “Gwaan, Prince Alla!” So I’d just say to Chinna play something like this… (Imitates melody to Children Of God) Bertram Brown would just watch! But Tappa Zukie loved his horns and would always tell Dean Fraser, Nambo and Deadly, “Try this now” “Try that now” He loved that! He was more a man who loved the arranging whereas Bertram would just sit back and let you do what you wanted to do.

And did the Soul Syndicate band do what they wanted?

Yes but all the while, Chinna and them would ask me, “What you like?” So on Bucket Go A Well they went (imitates bassline to Bucket Bottom) and I said, “Yeah man! Nice bassline!” so they played that. Because in those times, when you made a song, sometimes all of it came together – the instruments and everything. Obviously I couldn’t play them but all of the ideas used to come! You make up a song and you hear all the horns play in your mind so when you go in the studio you try to get it. But sometimes it’s very right and sometimes you’d say, “No man! Back weh man!” Most of the time, though, you’d say, “yes!” I would come with an idea and then Chinna would play something and it always sounded nice to me. I would say, “Yeah man. That reach! A right thing you play man!” I never really told them, “do this!” and they didn’t want to do it, and they never did something I didn’t like and said, “Make it stay man!” I never really went through that with Soul Syndicate or anyone else I sing with still.

Did you sing for any other big producers at the time?

No, just Freedom Sounds and Tappa Zukie. I was never an artist who just sang for plenty of people. I never wanted to go sing for Duke Reid because he was a retired policeman with a big gun and he’d fire it in the air! He was rough!

I never wanted to go sing for Duke Reid because he was a retired policeman with a big gun and he’d fire it in the air! He was rough!

And he didn’t like Rasta.

Yes that was the number one reason too! And I never wanted to go to Studio 1 because I heard enough rumours about him and Delroy Wilson how he abused him in certain ways. So I just used to sing for Freedom Sounds, Tappa Zukie and a few for Joe Gibbs.

Now, obviously there was a lot of political violence going on in West Kingston in the mid Seventies. How did this affect your life and your music?

Well in those times a Rastaman could go anywhere. He could pass through the PNP meeting and he could pass through the JLP meeting and nobody would trouble him. It wasn’t like in the later days when Rasta would get involved in politics. So the pure war didn’t trouble Rasta in those times then. You could pass through any political meeting and they would say, “A Rasta that man!” So it was easy in those times with politics. They didn’t really hurt Rasta then. Of course in the later days when you come to the nineties you have some Rasta starting to get involved. But before that when I was a little youth and Rasta didn’t sing those tunes everybody loved you.

What did you do in the 80s when the roots music went out of fashion?

I started fishing! I started catching some fish because some producers would come sometimes and say, “Me like you a do some song you know?” but they were too much gun tune and I said “No. Nah do that man. Me just gwaan catch some fish” because I lived right beside the fishing beach. I’d just go down there and you could get a boat for hire for cheap so I’d get some bait on my line and just go catch fish. Eat some, sell some! (laughs)

How long did you stay a fisherman? How did you restart your career?

Not too long. Until the 90s still. There was a man from Switzerland named Asher Selector who was in Jamaica in about ’98 and came to my home. The brethren said, “Bwoy, Alla, them a want you in Switzerland you know” and I said, “What? I don’t have a passport” and he said, “What?” and I said, “OK I’ll get a passport”. So in ’99 I started travelling to England and it started from that so I didn’t do the fishing so much.

Did Blood and Fire help your career by reissuing your material in 1997?

Blood and Fire was a great help. Because it was the first time in my life that I ever really got money off of music. So God bless those Blood and Fire people – straight. Those people helped me know I could get some money. Steve Barrow came to Jamaica through Freedom Sounds and found us and said they wanted to re-release those songs there. Because in those times that man would come for old songs that they wanted to re-release. They’d just come and look for the artists and the promoter directly. People like me and Congos, they’d come directly to us. I got paid from them and got my royalties every time. But I signed up for ten years and I think the ten years are up now.

Blood and Fire was a great help. Because it was the first time in my life that I ever really got money off of music

You’ve recorded for UK producers and engineers like Gussie P, Jah Warrior, Ras Muffet, – who is your favourite producer working today?

From the UK? (laughs) Jah Warrior man. I’d just sing man and those tunes would come forth. And went I went to Jamaica that man would send my royalties straight same way. Big up yourself Jah Warrior. He was my favourite one.

How does the roots of today compare with the old days?

Well with the roots of today, I feel like too many artists are following the same trend and the same melodies. Because if you listen to Luciano you hear plenty of people want to sound like Luciano with the same melodies. It’s not like the first time when you’d listen to Ken Boothe or Alton Ellis and you’d hear different melodies and everybody had a different distinction. Nowadays if a man sings about fire, everybody else wants to come and sing about the fire too and use the same melodies he used to sing it. Same pattern. Less creative the business is, and more of a money thing now. The first time a man would say, “I want to make some money” but they first time they’d also say, “Man I want create something. I want to sound like myself”. Now a man wants to sound like the next man because he feels he can get the money quicker.

But it’s nice when modern artists reference you isn’t it? Like when Tarrus Riley and Dean Fraser used the Stone rhythm for his song One Two Order. How does it feel to see the new generation of Rasta artists building on your foundation?

It felt good for me man. Because from him doing that the people remembered me again. They said, “Remember that artist who do him thing there? Prince Alla! Yeah man!” so he really did a good thing and kept my memory alive. I love it because the musicians that played it where the same musicians that originally played it. Sly & Robbie same way so it still had the vibes same way. They checked me and told me that they did it and I said, “Yes man. Big up yourself”.

What do you think of the heavy sounding digital UK roots that you have recorded in recent times?

Well to tell you the truth about me, from the time I was small my father used to have a little gramophone where he had all different records. So I used to listen to all different records, jazz and all those things there. Sometimes I would really feel the jazz and say, “Wha???” sometimes I’d really feel the calypso, the soca and so on. I just love music. Any music can make me feel certain things in my soul. Any rhythm because rhythms are just rhythms. Anyone who can make me feel Jah power there then I just love it. It doesn’t have to be reggae – it can be jazz or calypso or whatever. But if I feel it, I feel it. I mostly sing reggae because when you’re used to something you do it a certain way, but I love all music and I listen to all.

You played in the UK very recently. Do you find Jamaican audiences want to hear you play different tunes to UK ones?

Well I’ll tell you the truth again. There was only one song I really released in Jamaica and it was I Man Saw A Stone. In those times, most of the promoters would just sell your tune in Europe and tell you that, “Nothing a gwaan”. Then somebody would come from Europe and say, “You know Prince Alla I hear your tune and them thing there…” and I’d go to the promoter who would say, “Somebody up there pirate me! I’m going to go up there and sue them!” and the artist relaxes back again thinking they are going to find them and sue them. So in those times I never used to get money my brethren but it never used to trouble me because I loved the music so much. And I was just a single man with no family and no bills so I could just live down at the beach and sleep in a ranch and then go to sea and catch some fish and eat. But when you start having responsibilities you see it shouldn’t go so.

How are you being treated now in the music business?

Better than before. But still not by the local people like my brothers and sisters here. Mostly by people in England or Asher Selector in Switzerland. I know the vibes in Jamaica so I don’t really get too involved with the promoters here. It’s not all – because you have good ones still – but to get money from most producers in Jamaica you have to have a posse. You have to have five, six, seven, eight man who’d walk with you and they have to be bad boys so the promoter sees you with them and has to pay you up. You have to have people to watch your back and bodyguards and I don’t have those things so I prefer to deal with people in Europe more. They are more business people and deal with official things more whether black or white. Like I’ve been doing some things recently with a brother named Jah Youth and he is a black man and he is really good. In Jamaica it’s not that way! (laughs)

To get money from most producers in Jamaica you have to have a posse

As well as making music abroad you also appeared in the American film Holding On To Jah for Harrison Stafford and Roger Landon Hall. How was that experience?

I almost forgot about that one! Big up that brethren there man! That brethren is a good brethren to me materially and spiritually. I know when that comes out it will be nice because there are some nice interviews with nice artists and nice songs. He showed me a little clip of it but it wasn’t finished.

I’ve seen a preview copy. It has come out really well.

Big him up. Rastafari son that. A bassie by the name of Andrew brought him to me. So I went down to the fishing beach in Greenwich farm and did the interview with him. Then he came back and said it was going in the film and gave me some money and that so I say, “Yeah man, respect man!”

You got quite angry at one point when talking about Babylon and how Rasta people were treated when you were young.

Yeah man. Well sometimes when you’re talking about things at that particular moment you really feel it you know? But it’s not like it’s really on me still because it was a long time ago and we’ve had a long time to get ourselves straight so it doesn’t happen to us again. So the thing that is on us now as a Rastaman to really get himself unified and organised because those things haven’t happened. Because the reason those things happened to us where because we didn’t unify and have a voice. When you are single you don’t have a voice and everybody can come and mash you and step on you. So that is the focus I have now to really come to unify and have a voice. Things are better now – a million times better. Through even the reggae music too. When I was a youth the Rastaman couldn’t get any work. Nobody wanted him around the place. Nowadays you have a Rastaman who is a doctor in the Kingston public hospital. Rastaman are in politics big. Rastaman are pilots now. Rastaman have Bob Marley in the music so there are enough ways Rasta can edify themselves.

So Rastafarians need to be involved in the system?

It’s education and not just the spirituality thing alone. Rastafari is The Almighty but you have to have the education and the technology too to live in this age. The Rastaman is more advanced. One time the Rastaman would just go by himself into the country and leave the system and there was no business and all those things there. But now you have business in what goes on because everything affects you. You can’t be in the hills and hide by yourself. The system can still come and affect you so you have to stand more now. You cannot depend upon the donkey or the mule to carry things. In those days the Rastaman didn’t deal with trucks or buses but now you have to deal with those things because the donkey can’t work again. Animal brutality that! (laughs)

Rastafari is The Almighty but you have to have the education and the technology too to live in this age

What issues do you face as a Rastafarian living in Babylon today?

We’re free now but it’s the way we have to free ourselves. It’s just the unity of the Rastaman. That is the only thing. Because Jah has done everything already. Everything is set up already but it’s just us now. The greatest issue is we unify ourselves. More Rastaman in Jamaica need to come and make schools for children. Unity, not just through talk alone, but by taking some of the millions that they have and set up some things for the youth like schools so they can learn about their ancestry and Marcus Garvey and have a better tomorrow. Tomorrow is a change and it’s not today. So we should start to set it now. We plant the seed now but it’s not the same day that the seed is going to burst out of the ground. So we set it now and Rastaman should start up more schools and help the youth learn about themselves and see that violence is not the key. Violence is not the ultimate – it’s love. War is not the ultimate – it’s peace.

Why do people turn to violence?

Because growing up in Jamaica under a certain amount of slavery and oppression most people have a screw face but most of them don’t realize they can take the screw off of their face. Most of them blame people and say, “Why has them put me in all of this you know?” so they just stay in there. But somebody put you in so you come out now. But most people just stay there and complain about people who put them there so the next generation finds themselves there too. When they need to just think about coming out now and have unity with each other and set up things. Like education and technology.

What else can be done?

In Jamaica there are plenty of Rastaman who have plenty of things but most of them don’t do the right things with the things they have. Like set up factories to make things. Because when I was a youth the Rastaman used to be creative. They’d make pure mats, brooms, carvings all those little kinds of things but nowadays you don’t see that so much. Those things are missing. More youth end up on the street with no things he can be doing when he doesn’t have food. He just has to beg it or rob it. So more things need to be set up and Rasta must do that. We can’t leave it to the church alone. Everybody who talks about God should make sure the people have food. The Rastaman has to do it too. And don’t be selfish. I’m not saying all Rasta are like that. There are some Rasta that are doing great things in Jamaica but they want help from more Rasta. Big up all the Rastaman doing great things in Jamaica but it’s not just to issue the corn but to help the people plant it too.